Past the Salt

After 150 years of salt mining, a tidal marsh returns

This story originally appeared in bioGraphic, an online magazine about nature and sustainability powered by the California Academy of Sciences.

Perhaps unsurprisingly, taking photographs from a doorless helicopter was proving more difficult than San Francisco Bay Area photographer joSon had anticipated. Bundled in ski apparel and buckled into his seat, he had done his best to prepare. But the driving winds on this chilly November day quickly numbed his fingers, and more than once his camera smacked against his face as a gust rattled the two-seater aircraft. Four thousand feet below, the placid salt ponds that lured him to this precarious position draped the southern inland tip of San Francisco Bay like a multicolored quilt.

Like many Bay Area residents, joSon's first glimpse of the South Bay’s salt ponds was from the relative comfort of a commercial airliner. Descending into San Francisco International Airport, travelers glimpse an otherworldly landscape of geometric lines and vibrant colors fringing the jagged coastline and muddy blue-green of the bay—the result of more than 150 years of industrial salt mining. As bay water is pumped through a series of artificial ponds, sun and steady winds cause it to evaporate, leaving each pond saltier than the one before. And as the salinity changes, so do the pigmented microorganisms that thrive in the brine, giving each pond a unique color—from the lime green of Dunaliella algae in low-salinity pools to the rose-petal reds of salt-loving halobacteria in crystallization ponds.

The colors and patterns reminded joSon of rice paddies in Vietnam, where he spent part of his childhood and lived as a Buddhist monk. Captivated, he returned to the South Bay salt ponds again and again, dangling from a helicopter, often in frigid temperatures, over the course of two years to capture their “bizarre beauty.” Over time, he noticed a transformation taking place.

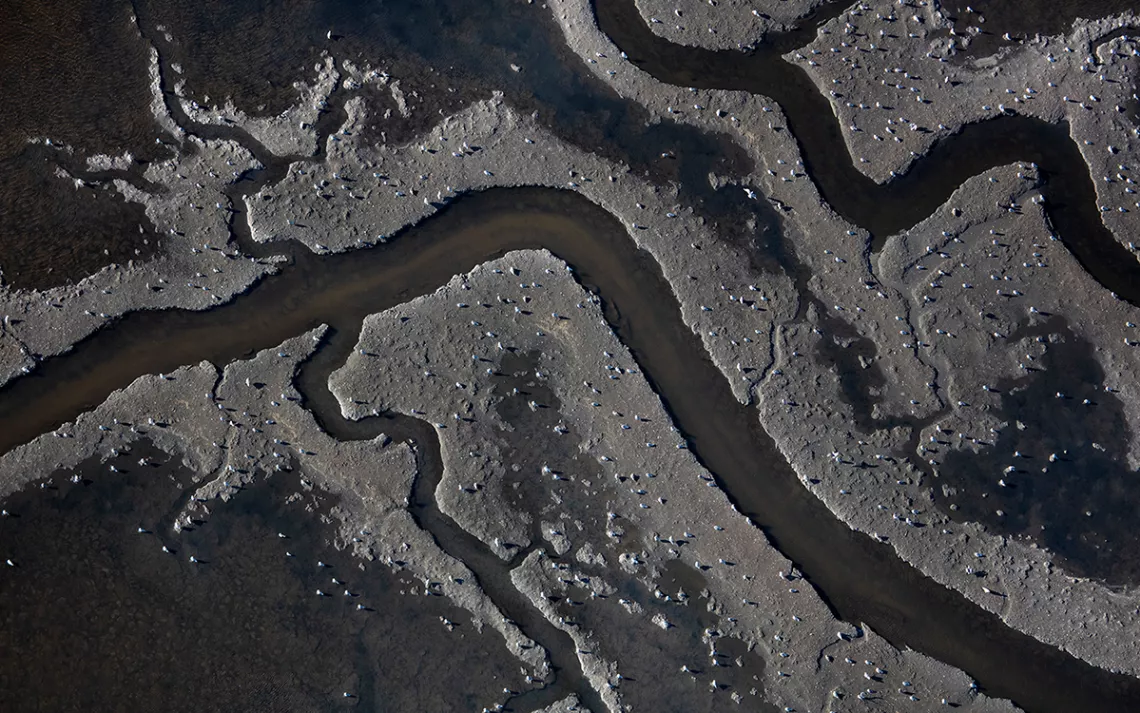

“Where some of the ponds once were, the locations were now flooded with seawater,” joSon told me. In place of the neon colors of industrial salt ponds, he began noticing “thousands of pearl-like brown and white dots”— flocks of American avocets (Recurvirostra americana) and other shorebirds returning to the South Bay.

Although he didn’t yet realize it, joSon was documenting one of the largest wetland restoration projects in US history.

In 2003, the multinational corporation Cargill sold more than 15,000 acres of its South Bay salt ponds—most but not all of its holdings—to the US Fish and Wildlife Service, California State Coastal Conservancy, and the California Department of Fish and Game. This sale launched the South Bay Salt Pond Restoration Project. In the decades since, a consortium of more than a dozen nonprofits and state and federal agencies have collaborated to return much of the area to tidal marsh by mid-century. In doing so, they hope to re-create habitat for beleaguered native species, restore the coastline’s natural flood resilience, and improve the overall quality of the South Bay’s coastal ecosystems.

But nature has adapted in ways that are complicating their efforts. While the salt ponds have undeniably had negative impacts on many species, including threatened Ridgway’s rails (Rallus obsoletus), they have unintentionally benefited others, like canvasbacks (Aythya valisineria) and buffleheads (Bucephala albeola), which overwinter on the shallow pools. More complicating still, the threat of climate change and sea level rise has been looming ever larger since the project’s inception. Restoring the wetlands requires balancing the needs of plants and animals—including humans—that have long populated the South Bay’s wetlands with those of species that have more recently come to depend upon the manmade salt ponds.

Despite their surreal present-day appearance, salt ponds have a history in the South Bay stretching nearly as far back as the wetlands themselves. Around 3,000 years ago, as the rapid rate of sea level rise driven by the end of the last ice age began to slow, marsh plants took hold along the edges of the bay. The increased vegetation trapped more and more sediment from upstream erosion and tidal deposition, leveling out the transition from water to land and allowing wetlands to rise above the tidal flats.

For millennia afterward, expansive mudflats bordered the South Bay’s shore, exposed twice daily at low tide. Upslope, verdant marshes were a meshwork of hundreds of plant species. Further inland still, bay water, filling natural depressions only during the highest winter tides, evaporated under the late-summer sun, leaving behind large natural salt deposits.

Even human harvesting of the ponds dates to prehistoric times. Long before Europeans arrived, Ohlone people crystallized salt on willow twigs or burned small patches of marsh plants to reap the salty ash left behind. Such harvests were bountiful enough to not only enrich the Ohlone’s own food but to also trade with other tribes throughout the region.

Archaeological surveys of Ohlone shellmounds—sacred sites often constructed for burials—give us an idea of the region’s biodiversity during these early stewards’ time. Though mostly composed of shells from bay mussels, clams, and oysters mixed with sand and clay, the mounds also contained remnants of other animals, including black-tailed deer, harbor seals, Chinook salmon, and even species no longer found in the San Francisco estuary, such as Tule elk and sea otters. In some instances, the interred were not humans but culturally significant species like the California condor (Gymnogyps californianus), which went extinct in the wild in the 1980s and has since been reintroduced through captive-breeding programs.

After arriving in the late 1700s, the Spanish quickly co-opted Indigenous salt-harvesting techniques and enslaved the Ohlone to produce salt for export to Europe. Still, this early salt production remained relatively small in scale, relying on natural salinas—the Spanish term for elongated, landward pools used to harvest salt—the largest of which was the 1,200-acre Crystal Salt Pond near the modern-day city of Hayward.

The South Bay’s first artificial salt ponds were built by a German settler named John Johnson in 1853. Even as he and others began manipulating the landscape, however, legal restrictions on how much acreage could be bought on credit meant that most salt ponds were small, family-run operations. Many families owned as few as 20 acres and built pond levees against natural creeks and sloughs, minimizing impacts on the local ecology.

Then, in 1868, California removed all acreage restrictions, clearing the way for land barons to purchase and “reclaim" vast swathes of wetlands. Almost immediately, speculators began buying up tracts of Bay Area wetlands with grand visions of industrialization to support the region’s burgeoning cities—themselves built atop meadows and oak woodlands. Within decades, shellmounds turned into shipping hubs, hunting grounds into game lodges, and family-owned ponds into corporate-owned saltworks.

While the rest of San Francisco Bay was being developed, the South Bay proved surprisingly difficult to tame. The salty soil made agriculture untenable, and the shallow, muddy bay bottom stifled developers’ dreams of building the world’s most valuable industrial harbor. Salt harvesting, however, remained profitable.

By the 1950s, artificial South Bay salt ponds, at this point almost entirely consolidated under the ownership of a single company called Leslie Salt, covered 25,000 acres and had consumed roughly half of historical tidal marshes. Levees crisscrossed the edges of the bay, segmenting the former marshes into pools of varying salinities and upending the hydrology that had long fed the wetlands. The wetlands that weren’t used for salt production were snatched up by real estate developers, who dredged, filled, and built upon them to create communities like Foster City and Redwood Shores.

These projects, combined with a report from the Army Corps of Engineers advocating further filling of the bay, sparked outrage among ecologically conscious locals who wished to preserve the space for public access and wildlife. In 1961, environmentalists formed the Save San Francisco Bay Association (later known as Save the Bay, a key partner on the South Bay Salt Pond Restoration Project). The organization successfully advocated a ban on filling the bay to build more housing. In 1974, the Don Edwards San Francisco Bay National Wildlife Refuge, the nation’s first urban wildlife refuge, was established on land formerly owned by Leslie Salt. A few years later, Leslie sold their remaining holdings to Cargill, which harvested and sold a million tons of salt per year at its peak—slightly more than the weight of the nearby Golden Gate Bridge. Of particular interest to joSon, some of that salt helped produce the napalm that the US military used to destroyed villages and lives during the Vietnam War.

By the time Cargill sold most of its ponds to the State of California, setting the stage for the West Coast’s largest wetlands restoration project, San Francisco Bay’s estuary was in dire straits. In total, somewhere between 80 and 95 percent of tidal wetlands had been degraded or developed. Removal of groundwater for reclamation had caused the land to actually sink in places—as much as 13 feet in the Santa Clara Valley—leaving the surrounding communities more vulnerable to flooding. Just 1,000 of the original 6,000 miles of channels that fed the bay and deposited the sediment and freshwater necessary for the wetlands to thrive were left intact.

The fabric of interwoven wetland ecosystems that provide natural flood protection and habitat for thousands of species had been unraveled. One of the few, frayed threads remaining were the salt ponds.

When John Johnson, Leslie Salt, and other fortune-seekers began diking the South Bay for salt ponds, they likely put little thought into what it would mean for the surrounding waterfowl, shorebirds, and other wetland species. But while they were molding the land to their own purposes, nature was adapting to them. And though many species were forced out, others found sanctuary in the salty South Bay.

For threatened western snowy plovers (Charadrius alexandrinus nivosus), driven from the shorelines they historically populated by beachgoers, the salt ponds granted reprieve. Earthen islands built to dampen the tidal erosion of the levees and dried salt beds proved well-suited for camouflaging the sandy-feathered shorebirds.

Likewise, migratory water birds left with few places to roost and forage during their yearly journey along the 9,000-mile Pacific Flyway, a migration corridor stretching from Alaska to Patagonia, found a feast of brine shrimp and other invertebrates in the calm, shallow salt ponds. During one spring migration in the 1980s, researchers tallied more than 200,000 birds in a single pond.

“The whole Pacific Flyway comes through here,” says Dave Halsing, a California Coastal Conservancy scientist and executive project manager for the South Bay Salt Pond Restoration Project (SBSPRP). “For those couple of weeks, this is all there is. The whole Central Valley of California used to be marshy open space. Now it’s all subdivisions and farmland. The stopover has become the bay.”

Even humans have benefitted to some degree from the salt ponds. Though not nearly as effective as wetlands, the ponds’ levees provide an important buffer between the bay and the surrounding communities, reducing flood risks during heavy rains and high tides.

Taking all of these unintended consequences into consideration has complicated efforts to restore the South Bay. “If all we had to do was tidal marsh restoration, it would be very simple,” Halsing says. “But it’s not.”

In response, the SBSPRP is taking an adaptive approach, essentially treating the whole 50-year project as a series of smaller, more manageable endeavors, with the overall goal of restoring at least half of the 15,100 acres to tidal wetlands while maintaining current levels of flood protection and biodiversity. What this means in practice is breaching many of the ponds, preserving others as they are, and enhancing the rest by adding artificial islands for roosting, or altering salinity and water levels to attract certain species. Then the team monitors how those changes impact various species and adjusts its strategy as needed.

From a distance, the work looks like a child’s sandbox, with mounds of earth surrounding bright-yellow mechanical beasts of all shapes and sizes. Up close, it’s not all that different from any other construction site; half a dozen people or so busying about in hardhats and bright-colored vests, the loud rumble and hydraulic hisses of excavators and bulldozers roaring to life.

Once the groundwork has been laid according to a specific pond’s fate—levees raised or lowered, earth graded to the desired slope, flood channels added or gated—volunteers from Save the Bay work with project biologists for what Donna Ball, a San Francisco Estuary Institute biologist and lead scientist on the SBSPRP, says is one of the most important parts of restoring the ecosystem: replanting vegetation. “Putting plants in is really the habitat piece,” Ball says. “It’s really the meat of trying to think about each species and what they might need.”

To date, around 3,000 acres have been restored to tidal wetlands, and 700 acres of ponds have been enhanced. Just as the first plants 3,000 years ago provided the foundation for the wetlands—and all the biodiversity they support—these initial plantings are bringing life back to the landscape.

In 2014, just eight years after breaching the first ponds, Ridgway’s rails were discovered meandering through the marsh. A year later, salt marsh harvest mice (Reithrodontomys raviventris), an endangered species endemic to the Bay Area, scampered around dense carpets of pickleweed. Even threatened longfin smelt (Spirinchus thaleichthys) and other local fishes were visiting the surrounding waters in greater numbers than before.

The wetlands were returning much faster than anyone had anticipated. “We had thought that it would take longer,” Ball says. “It’s great to know that we’re having a positive effect.”

Importantly, even with the number of artificial salt ponds shrinking, improvements to those that remain has actually increased migratory waterbird numbers. A study from the US Geological Survey found that between 2002 and 2014, the number of overwintering water birds (both waterfowl and shorebirds) that stopped over in the project area more than doubled. By comparison, in nearby ponds still owned by Cargill for salt production, there was virtually no change in water bird visitation over roughly the same period.

And though they haven’t experienced a similar surge, western snowy plover populations have held steady thanks to habitat enhancements, including spreading oyster shells on dried salt ponds for improved camouflage and removing nearby perches used by predatory raptors.

The SBSPRP was restoring balance to the South Bay wetlands. But increasingly, the weight of climate change has been threatening to tip the scales back out of whack. To ensure their progress would not be undone, the project leaders had to start planning not only for what the wetlands needed today but also for what they will need in the near future.

As I stand on one of the easternmost levees of Ravenswood, an open space preserve along the shore of the South Bay and one of three main restoration sites for the SBSPRP, it’s easy to grasp the Bay Area’s vulnerability to climate change. Within a seven-mile radius of me, over largely flat terrain, lies Redwood City, Palo Alto, and Menlo Park, with a combined population of nearly 200,000 people. Water from the bay practically laps at my feet.

According to a recent report from the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration, by 2050 sea levels along the West Coast are expected to rise between four and eight inches. At the same time, flooding is expected to become more frequent and severe, with major flood events occurring five times as often.

While climate change had long been considered by the SBSPRP, Ball says the increasingly dire predictions about when the Bay Area could feel its effects—and how severe those impacts could be on people and wildlife—has ramped up the project’s urgency, since healthy wetlands can serve as a natural barrier to flooding and storm surges.

The key word, however, is healthy. Even under ideal conditions, it takes time for restored wetlands to go from sparse and fragile vegetation to lush and robust. And rising seas and severe storms are not ideal circumstances for adolescent wetlands, inundating or robbing the young upstarts of the sediment they need to develop and thrive. The sooner ponds can be breached and restoration started, the more likely it is that the wetlands will be able to mature into a resilient ecosystem. Indeed, a 2019 study from Point Blue Science, a key partner in the restoration project, showed that if tidal fluctuations weren’t restored to certain parts of the project area by mid-century, they might never accrete enough sediment to survive.

Even mature wetlands will eventually succumb to rising seas if rates of erosion and inundation outpace sedimentation. That is, unless they have somewhere to run.

While plants might appear immobile, over long periods of time plant populations can move in response to their environment. For wetland flora such as salt marsh gumplant (Grindelia stricta) or alkali heath (Frankenia salina), both of which love salty soil but prefer drier conditions, this means extending their roots upland as water levels rise.

Historically, there was plenty of space for Bay Area marshes to migrate. Gradually sloped transition zones, or ecotones, hundreds to thousands of feet wide, bordered much of the wetlands, providing a spectrum of overlapping habitats from subtidal to salt marsh to upland meadows. Today, development has encroached on 90 percent of those areas, reducing them in most places to just a handful of feet.

To give the South Bay’s nascent wetlands a fighting chance in the face of climate change, the SBSPRP is adding ecotones to many of their tidal marsh restoration sites during the latest phase of construction. Ecotones aren’t possible everywhere, but they have wide-ranging benefits. In addition to restoring wildlife habitat and tempering floods, they can preserve the beauty and accessibility of the wetlands for the region's human inhabitants.

Rather than protecting the Bay Area from floods by building a levee that would turn San Francisco Bay into a giant bathtub, Ball says, ecotones and other nature-based solutions can help “maintain this habitat—even for people.”

On a sunny early afternoon in spring, I visit Eden Landing Ecological Reserve, another of the main project sites for the SBSPRP. At the entrance, a sign briefly nods to the complicated history of the landscape, no doubt preparing visitors who might soon be confused by the presence of levees, flood control gates, and managed ponds in an ecological reserve. Moments into my walk, however, I feel no confusion: This land is undoubtedly wild.

As I head toward the trail loop, marsh wrens (Cistothorus palustris) burst from the grasses lining both sides of the path, chittering in alarm at my presence before sinking back into the tangle. To my right, a raft of American avocets, heads golden brown, beaks slightly upturned, bob lazily in a shallow pond. To my left, a long-billed curlew (Numenius americanus) slinks through the tidal mud flats foraging for invertebrates.

Further down the trail, I find myself face-to-face with the full scope of the restoration project. I pass a half dozen ponds of various water levels and shades of yellow, hinting at their differences in salinity. In most, an artificial island emerges a foot or so above the surface. I walk atop levees for most of the journey, occasionally crossing over a flood gate separating pond from pond or pond from bay. At one of the outermost points from the trailhead I come upon a dried salt bed, a parched moonscape shattered at the edges and scattered with oyster shells.

And at each turn I find signs of life. Goldfinches, yellowthroats, and song sparrows flitting through the tall upland grasses. Ducks, herons, and egrets along the channels bordering the tidal marshes. Sandpipers, willets, and stilts on the islands of the managed ponds. I even come across an unattended egg nestled atop a patch of clover on the bank of the levee.

I feel grateful for this space, a stone’s throw from busy metropolises and yet a world away. But strangely, I also find myself feeling thankful for the salt ponds—not only those that have been restored and enhanced but also their manmade predecessors. Almost all of the restorable land along the shores of the South Bay exists because the industrial salt ponds unintentionally preserved this place. If not for the salt ponds, the area would have almost certainly been developed.

The tension between what I know of the land’s tumultuous history and the peace I find there makes me think of joSon. Drawing on his past as a Buddhist monk, the photographer considers the restoration project a form of rebirth, a way of healing the wetlands while reconciling the land’s past traumas. “The concept of rebirth defines how we grow and redefine ourselves by simultaneously shedding and embracing our painful past,” he says. For him, the arc of the salt ponds’ history offers a way of thinking about how individuals, cultures, and places can “adapt and move on.”

Near the end of the trail, I come across the relics of a former salt-harvesting operation, retained for posterity. Beyond, wooden pilings worn smooth by tides and time emerge from mudflats and murky ponds, supporting ghost structures no longer present. As the wetlands devour the scars of industry, a semblance of what this landscape once was—and has always been to the Ohlone, who continue to hold ceremonies at shellmound sites—is re-emerging: A sacred place for plants, animals, and people, a wetland in a constant cycle of being reborn.

The Magazine of The Sierra Club

The Magazine of The Sierra Club