Nuclear War Makes a Comeback

It's time to revisit the old fear that kept your parents up at night

Photo by Kremll/iStock

On websites where policymakers, scholars, and military leaders gather, concern about the possibility of nuclear war has been rising sharply in recent months as China, the United States, and Russia develop new weapons and new ways of using old ones.

On War on the Rocks, an online platform for national security articles and podcasts, Tong Zhao, a senior fellow at the Carnegie-Tsinghua Center for Global Policy, reported August 11 on public calls in China “to quickly and massively build up its nuclear forces” on the theory that only a “more robust nuclear posture” would prevent war with the United States.

The biggest nuclear arms budget ever is nearing approval in the US Congress, and the Trump administration has raised the possibility of resuming nuclear tests. President Trump has pulled the United States out of the 1987 Intermediate-Range Nuclear Forces (INF) treaty with Russia, while the New Start Treaty capping Russian and US nuclear warheads and delivery systems is set to expire next February if the two countries don’t agree to extend it.

For its part, Russia appears poised to equip its navy with hypersonic nuclear strike weapons, and according to the British newspaper The Independent, “The Russian premier has repeatedly spoken of his wish to develop a new generation of nuclear weapons that can be targeted anywhere on the planet.”

Meanwhile, momentum to stop the proliferation of nuclear weapons has faltered. Nine nations now hold nuclear arms in an increasingly unsettled international scene. Recent research has shown that a nuclear exchange between just two of those with lesser arsenals—India and Pakistan—“could directly kill about 2.5 times as many as died worldwide in WWII, and in this nuclear war, the fatalities could occur in a single week.” Burning cities would throw so much soot into the upper atmosphere that temperatures and precipitation levels would fall across much of the earth—bringing widespread drought, famine, and death.

Clashes between India, Pakistan, and other nuclear-armed states have become frequent enough that the International Red Cross marked the 75th anniversary of the bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki with a warning: “[T]he risk of use of nuclear weapons has risen to levels not seen since the end of the Cold War.”

For 75 years, the nuclear Sword of Damocles has dangled over the earth. There is widespread agreement among analysts that the long lull may soon be over—owing, in part, to the end of the Cold War. During those decades, the United States and the USSR cooperated not only to avoid bombing each other into oblivion but also to discourage other nations from gaining their own nuclear arms, in part by spreading their nuclear umbrellas over their allies.

That international system has dissolved. In addition to the United States, Russia, and China, other nations have nuclear weapons and more are likely to soon acquire them. And a new possibility has appeared on the horizon: the increased likelihood that nuclear weapons could be introduced into conventional warfare in regional wars.

In a monograph published by Lawrence Livermore Laboratory, US defense policy and strategy analyst John K. Warden writes that “in the capitals of potential adversary countries,” the idea is taking hold “that nuclear wars can be won because they can be kept limited, and thus can be fought—even against the United States.”

What can the United States do to convince adversaries not to introduce nuclear weapons into a conventional war—to make clear, in advance, that taking such a step would lead to fatal consequences for the country that took it?

Make every day an Earth Day

Get articles like this one sent directly to your inbox.

With this action you affirm you want to receive Sierra Club communications and may vote on policy designated by the Sierra Club Board.

The answer from the US national security establishment, as the fiscal 2021 defense budget suggests, is a readiness to fight fire with fire: If the “adversaries” of the United States hold out the threat of introducing nuclear weapons in a conventional war, then (the argument goes) they should expect that the United States will respond in kind.

How many weapons and delivery systems would that require? A lot, according to the nuclear budget for the Departments of Defense and Energy now going through Congress. At a time when COVID-19 has shaken the foundations of the federal budget, Congress is close to approving $44.5 billion for fiscal 2021 to modernize nuclear warheads, delivery systems, and the infrastructure that supports them.

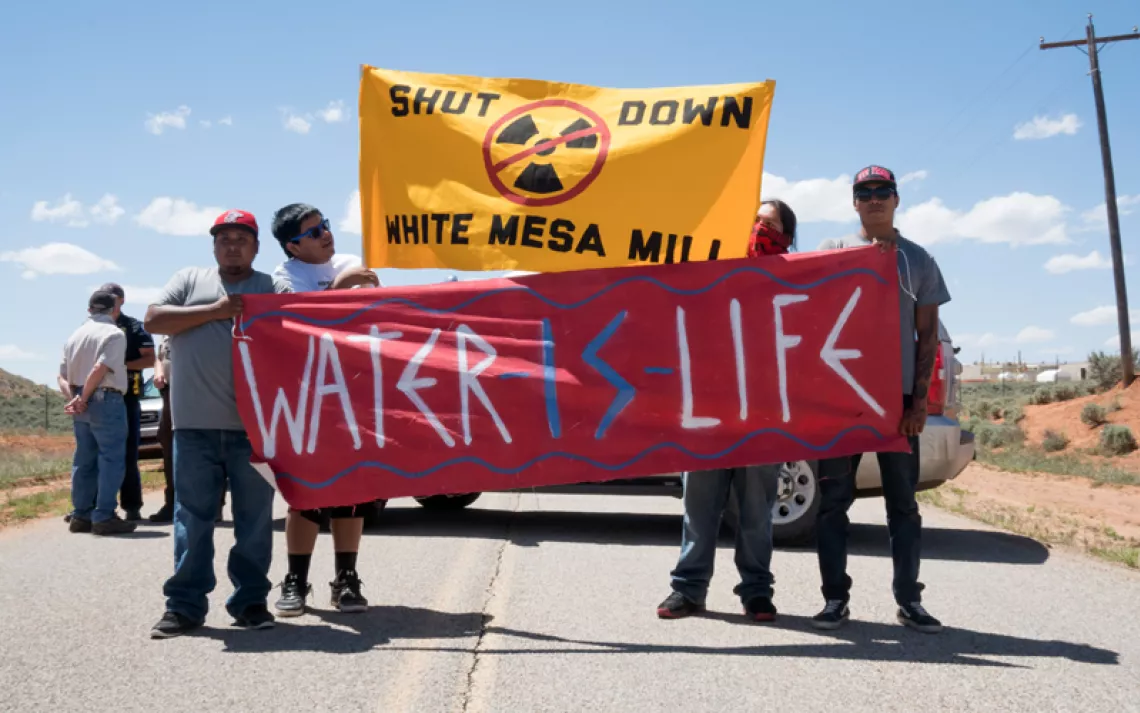

Sierra Club nuclear policy director John Coequyt has called on Congress “to resist the current renewal of the nuclear arms race and to ban the use of nuclear weapons,” and Sierra Club members have mobilized to try to stop funding for nuclear war projects in their neighborhoods.

In South Carolina, for instance, Tom Clements, Sierra Club member and director of Savannah River Site Watch, has joined other groups in challenging plans for expanded plutonium pit production at the Savannah River Site. And the Ohio Sierra Club’s Nuclear Free Committee has opposed production at the Portsmouth Nuclear Site in Piketon of “high-assay low-enriched uranium” that could be upgraded for weapons use, in the United States or elsewhere.

While such efforts often focus on local effects of nuclear weapons production, they also manifest a larger concern. Says the Club’s Nuclear Free Core Team’s Mark Muhich, the renewed nuclear arms race is “an existential threat both to human civilization and to the earth.”

Join the conversation in the Nuclear Free Campaign room of the Sierra Club Grassroots Network.

Read the Sierra Club’s policy statements on nuclear weapons here.

The Magazine of The Sierra Club

The Magazine of The Sierra Club