November Stargazing: Patterns and Portents

We may take comfort in gazing at the stars, but they are certainly not shining for us

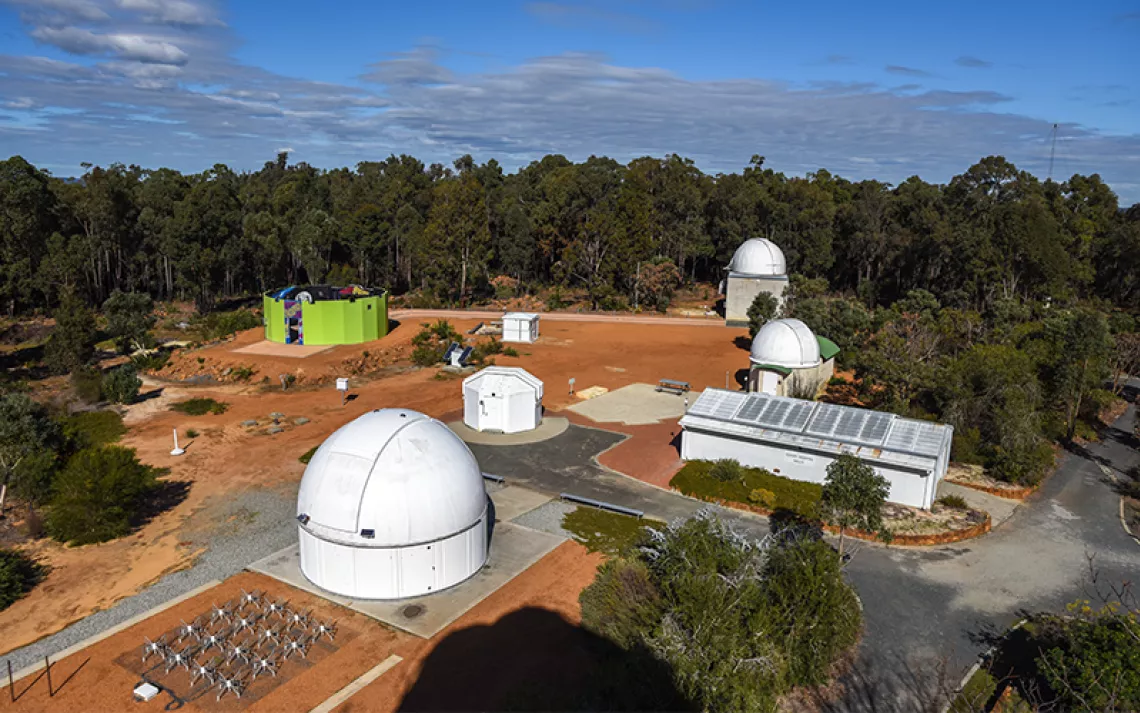

Photo by Jeremy Miller

The voice of Ray Davies cuts through the night as I carry my telescope from the house to the yard.

Well, once we had an easy ride and always felt the same

Time was on my side and I had everything to gain…

The scope tonight is pointed at a massive cloud of interstellar gas in the constellation of Cygnus, known as NGC 7000. Some see in its shape an outline of our home continent, hence its common name—the North America Nebula. For the past few weeks, we’ve had rare clear skies in the San Francisco Bay Area, and I’ve been taking advantage of them, dragging out my gear almost every night, letting the scope and camera drink in the darkness.

Let it be like yesterday

Please let me have happy days...

I struggle to stay awake as the camera, telescope, and mount perform their coordinated digital dance. Four hours. Five hours. Six. The photons pile up on the sensor, painting the distant scene. When I finally get outside to break the gear down in the early morning hours, removing the telescope from the mount, untangling the knot of cords, hauling the whole assemblage of gear inside, Orion glimmers overhead. The world is, for a few precious moments, quiet, calm.

Where have all the good times gone?

My backyard has, of late, become a refuge as the world struggles to free itself from the clutches of a pandemic that has now killed more than 228,000 people across the US and more than a million people globally. The night sky is my retreat from the lies, race-baiting, and anti-environmental rhetoric that pours daily from the White House. Closer to home, my father—my best friend, a man who worked for 40 years as a firefighter—is now in a pitched battle with cancer.

Which is to say, the beauty of the stars has lately become tied up in my mind with the uncertainty of the future. In the depths of night, questions swirl: Will my father be with us a year from now? Will Trump be ousted? Will our democracy and planet survive?

Faced with difficult questions like these, we often turn to nature for answers, looking for patterns that we might read like a code. Those patterns turn out to be mostly reflections of ourselves. We find witches’ faces in a fog bank, our grandfather’s profile in the swirl of milk in a cup of coffee, Jesus’s visage on a piece of toast. In his notebooks, Leonardo da Vinci described the phenomenon of seeing “battles and figures in action; or strange faces and costumes, and an endless variety of objects” in the contours of a stone wall.

The face-seeing phenomenon is so common that scientists have given it a name: pareidolia. At one time, this quirk of the human mind may have conferred some advantage, perhaps giving our early ancestors an evolutionary leg up by allowing them to pick hostile faces out of a complex background.

The cosmos have long been a focal point for those seeking to understand what the future holds—in particular by studying the motion of the planets as they pass through the 12 constellations of the zodiac. With its star charts and elaborate interpretations, the pseudoscience of astrology may seem like a step-cousin of astronomy. Perhaps this is why so many have fallen under its sway. Shakespeare wrote of “star-cross’d lovers” and consequences “yet hanging in the stars.” Ronald Reagan consulted an astrologer in the White House, and business magnate J.P. Morgan reputedly checked his horoscopes before making key investments. The ancient pastime has made a comeback in recent years, endorsed by a parade of celebrities including Selena Gomez, Kim Kardashian, and Lady Gaga. Because we have made ourselves the center of our own universe, we assume that the stars must be speaking to us.

It takes a lot of intellectual courage to admit to ourselves that we are not the center of things—that our existence as a species is, by all accounts, the result of exquisite chance. Fifteenth-century astronomer Nicolaus Copernicus proposed that Earth was not the center of the universe but one of several planets moving in orbit around the sun. The American astronomer Edwin Hubble determined that the “fuzzy” patches that had appeared in telescopes for centuries, confounding astronomers since the time of Galileo, were distant galaxies unto themselves. By examining the properties of their light, their so-called red- and blue-shifts, Hubble deduced that the galaxies were not stationary but rapidly moving. Now for the strange part: Hubble observed that the farther away from Earth a galaxy was, the faster it receded from us. This led him to posit that the universe was expanding at great speed—a frightening and destabilizing thought, particularly at the present moment, when so much seems to be out of our control.

Robinson Jeffers was a poet whose mind was of a scientific bent. His idea of “inhumanism” seems to me to be the literary summation of the lineage of scientific discoveries that have hammered away at the pedestal human beings placed themselves upon. In his poem “Carmel Point,” Jeffers looks out on the sea-pounded coastline of Big Sur, marveling at the convolutions of the rock and the “extraordinary patience of things” until the place is “defaced with a crop of suburban houses.”

“Now the spoiler has come,” Jeffers teases. Asking, of the place, “does it care?”

Not faintly. It has all time. It knows the people are a tide

That swells and in time will ebb, and all

Their works dissolve. Meanwhile the image of the pristine beauty

Lives in the very grain of the granite,

Safe as the endless ocean that climbs our cliff.—As for us:

We must uncenter our minds from ourselves;

We must unhumanize our views a little, and become confident

As the rock and ocean that we were made from.

Writing in the aftermath of World War I, Jeffers, like Copernicus, was making an urgent plea for human beings to “uncenter” themselves from their conception of reality. Anthropocentrism, he believed, led inexorably to war, environmental blight, and, ultimately, our destruction.

When I look through my images of NGC 7000 the next morning, I’m struck by how its complex dust and cloud formations billow like smoke. Within the maelstrom lies a beehive of stars visible only to the camera. Zooming out reveals the nebula’s outline, which, indeed, does resemble the North American continent—a beautiful coincidence and nothing more. As tempting as it is to see ourselves reflected in the contours of distant cosmic formations, to read our fate in the motion of the planets, we should resist the urge.

Instead, we must be humble and attuned to what the present moment asks of us—to put on a mask, to cast our votes and cast out hatred, to salvage what remains of the natural world and, by extension, our humanity. As for my father, the path is filled with uncertainty. Whatever lies ahead for the planet, our country, and my dad, I take solace in knowing that we are not ruled by some silly concept of cosmic intervention. We are a small species living on a small planet. But, collectively, we do have the power to change course, and to weather the bad while we seek good times ahead.

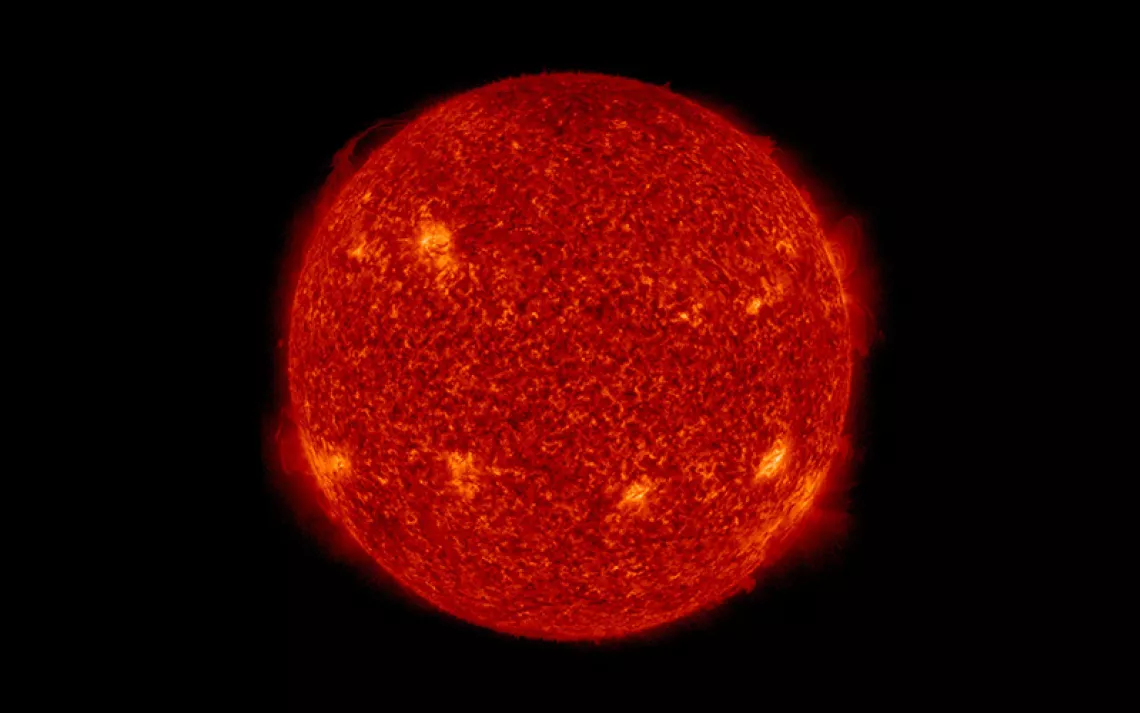

WHAT TO LOOK FOR IN NOVEMBER

This month, the summer triangle of Vega, Altair, and Deneb, in the constellation Cygnus (not far from NGC 7000) make their exit as the winter stars begin to dominate the night sky. In the early evening look to the northeast for an unmistakable sign of colder nights—the bright yellow star Capella, in the constellation Auriga. Capella (Latin for “female goat,” and sometimes referred to as the “Goat Star”) is a fascinating object, similar in color to our own sun. Powerful telescopes have revealed that Capella is, in fact, two luminous yellow stars, both much larger and brighter than the sun, locked in a tight orbit around each other.

November’s full moon, named for America’s largest rodent, arrives on November 30. The Beaver Moon was named by North American tribes who noted that its arrival coincides with the aquatic mammal’s retreat from open water to the warmth of its den.

November also brings the Taurids meteor shower, which is actually two separate events: The South Taurids and The North Taurids. Taking place about a week apart, these showers are somewhat unpredictable but seem to peak in seven-year intervals. The last of these came in 2015, when meteor watchers reported several bright fireballs between November 5 and 12. While this year’s show will probably not be so spectacular, there is a chance to see five or more bright streaks every hour. To find the meteor activity, look for the prominent V-shaped constellation of Taurus, the Bull, around November 11. The moon will be waning and dim enough to allow stargazers to tease out fainter streaks throughout the night.

The Magazine of The Sierra Club

The Magazine of The Sierra Club