Navajo Nation Council Rejects Mega-Development Escalade, Tramway

Tribes set aside differences to defeat the billion-dollar Grand Canyon development

Members of Save the Confluence celebrate after the failure of the Grand Canyon Escalade legislation. | Photos by Donovan Shortey

A six-year battle to stop a billion-dollar tourist development on Navajo Nation land ended victoriously for tribal conservationists and their allies this week when the Navajo Nation Council rejected Grand Canyon Escalade. Meeting in a special session on Tuesday, the council voted down legislation to authorize the project by a resounding 16-2 margin.

“There was a big crying session after the vote,” says tribal activist Sarana Riggs, an organizer with the Grand Canyon Trust. “Now families in the area can live without this threat that has loomed over them for the last six years.”

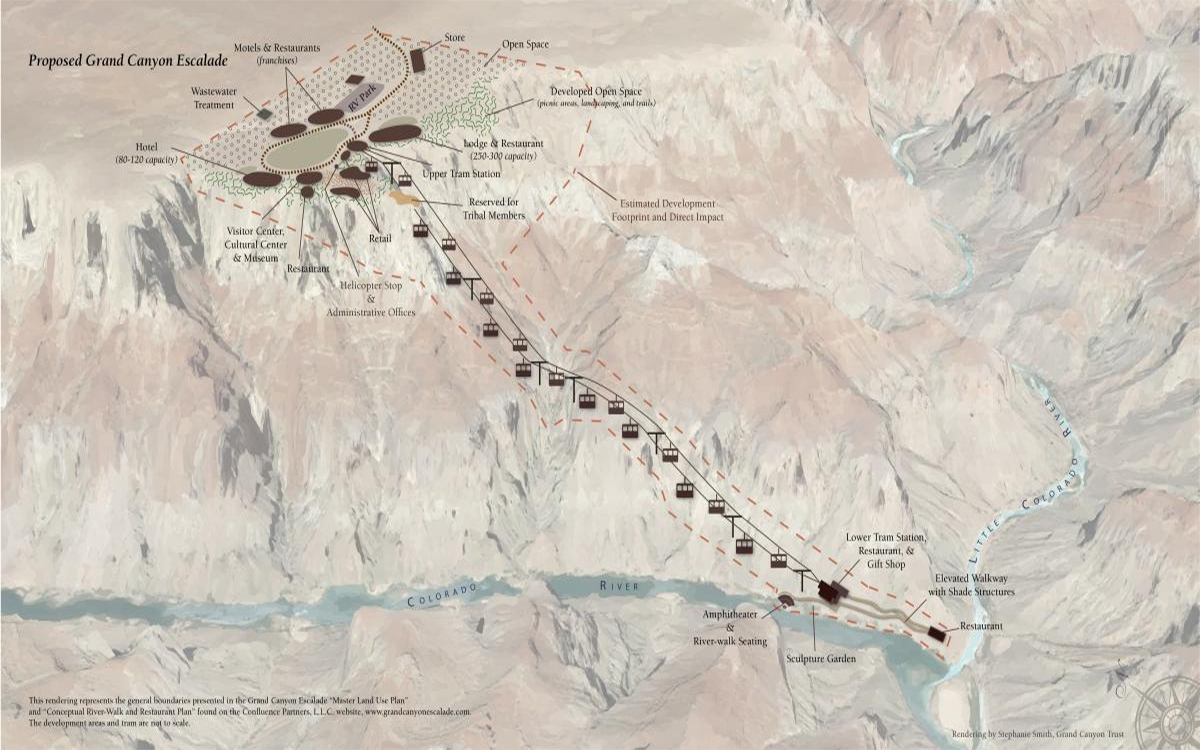

Grand Canyon Escalade, the vision of Phoenix developer Confluence Partners LLC, proposed to build a hotel, restaurants, an RV center, and other tourist attractions on the canyon rim. Most controversial, though, was a proposed 1.4-mile tramway that would shuttle up to 10,000 visitors a day to the confluence of the Colorado and Little Colorado Rivers—a site held sacred by Navajo, Hopi, Zuni, and other Native American tribes who trace their ancestry to the Grand Canyon.

“This was a big project with lots of money behind it that had momentum,” says Roger Clark, a colleague of Riggs's at the Grand Canyon Trust. “When we took up this fight, a lot of people thought Escalade was a done deal. But in the end, tribal leaders saw that it would forever alter the Grand Canyon and take away traditional uses for many tribes.”

A tacit agreement among tribes in the area to set aside historical differences and present a unified front in opposing Escalade was key to its defeat. “Hopi, Zuni, and Acoma leaders were all present at the council’s special session,” Riggs says. “All the tribes I’ve heard from are really happy and excited. This decision is so important for preserving our cultural heritage. Our ancestral homelands are in the Grand Canyon. Our ruins and sacred sites are there. Our traditional songs and prayers come from there.”

Escalade divided the Navajo community, as the developer promised it would bring jobs and profits to locals. Among the project’s early supporters was former Navajo Nation president Ben Shelly, who promoted Escalade as a potential bonanza for a tribe saddled with stubbornly high unemployment and poverty rates.

But the deal required the Navajo Nation to pony up $65 million for roads, water, power lines, and other infrastructure, and there were deepening concerns over water use and how to deal with wastewater at the tramway’s terminus inside the canyon. The National Park Service came out against Escalade in 2014, and current Navajo Nation president Russell Begaye, elected in 2015, vehemently opposed the project.

Courtesy of Stephanie Smith, Grand Canyon Trust

Central to Escalade’s ultimate demise was the work of Save the Confluence, a Navajo coalition that emphasized the cultural threats it posed, and the Grand Canyon Trust, which 20 years ago had the vision and foresight to develop a Native American program. Both groups placed the Grand Canyon’s cultural resources on an equal footing with its natural resources in making the case against Escalade.

For the river-running community, which was adamantly opposed to Escalade from the beginning, the Little Colorado/Colorado confluence is hallowed ground. It can only be reached via several days on the river or a long, steep hike from the rim. There, the jaw-dropping beauty of the Little Colorado’s aquamarine waters meet the darker, silt-laden main stem of the river. Many tribes view the confluence as the place where woman joins with man. It’s also where one enters the Grand Canyon proper.

“The confluence is a delineation point, for sure,” says Robby Pitagora, a conservationist and a river guide for over 35 years. “From Lees Ferry, the traditional starting point for a Grand Canyon river trip, to the confluence, you’re actually in Marble Canyon. Then you round a big corner right at the confluence and you’re in the Grand Canyon. It’s a major dividing line.”

In the fall of 2015, a group of tribal leaders and representatives from conservation groups undertook a weeklong river trip, starting at Lees Ferry. Organized by Roger Clark and led by Pitagora, the journey culminated in a ceremony at the confluence, presided over by Navajo, Hopi, Zuni, and Hualapai leaders. Out of this “Gathering Down the River” emerged the Grand Canyon Cultural Conservation Alliance, of which the Sierra Club is a charter member.

“That trip really helped solidify the inter-tribal cooperation that was so critical to this victory,” says Riggs, “but I’m not sure we’d be where we are today without the support of the non-tribal allies who worked with us. Groups like the Sierra Club helped tell the story and spread the word.”

Clark emphasizes that the fight to stop Escalade was always led by tribal members, not driven by an outside agenda. “Our role was to be advisors and support the strategic direction outlined by Save the Confluence,” he says. “They provided the leadership, and we helped enable the will of the people.”

Above: Inside the Navajo Nation Council Chamber during the Grand Canyon Escalade special session on Oct. 31, 2017.

Below: Rita Bilagody embraces another special session attendee in relief after the defeat of the Grand Canyon Escalade legislation.

As the special session of the Navajo Nation Council approached, Confluence Partners saw the writing on the wall and tried to sweeten the deal by offering to build a Boys and Girls Club for local residents. Clark says the offer only served to underscore how out of touch the developer was with the community. The council was far more persuaded, he feels, by seeing the elders and elected leaders from other tribes in the council chambers.

“We’re all breathing a huge sigh of relief,” Riggs says. “But this is just one battle in the bigger fight to protect all of our cultural sites; places like Bears Ears. We have to protect our traditional way of life, our identity, and where we come from. We need to respect natural law—water, air, land, and the elements all around us that we can’t see but we feel in a breeze that touches our skin. These are deities reminding us that water has rights, too. Waters can’t speak for themselves, but we can speak for them.”

The Magazine of The Sierra Club

The Magazine of The Sierra Club