Nature Is for All of Us

Black people face enough barriers to enjoying the outdoors—self-defeating stereotypes should not be one of them

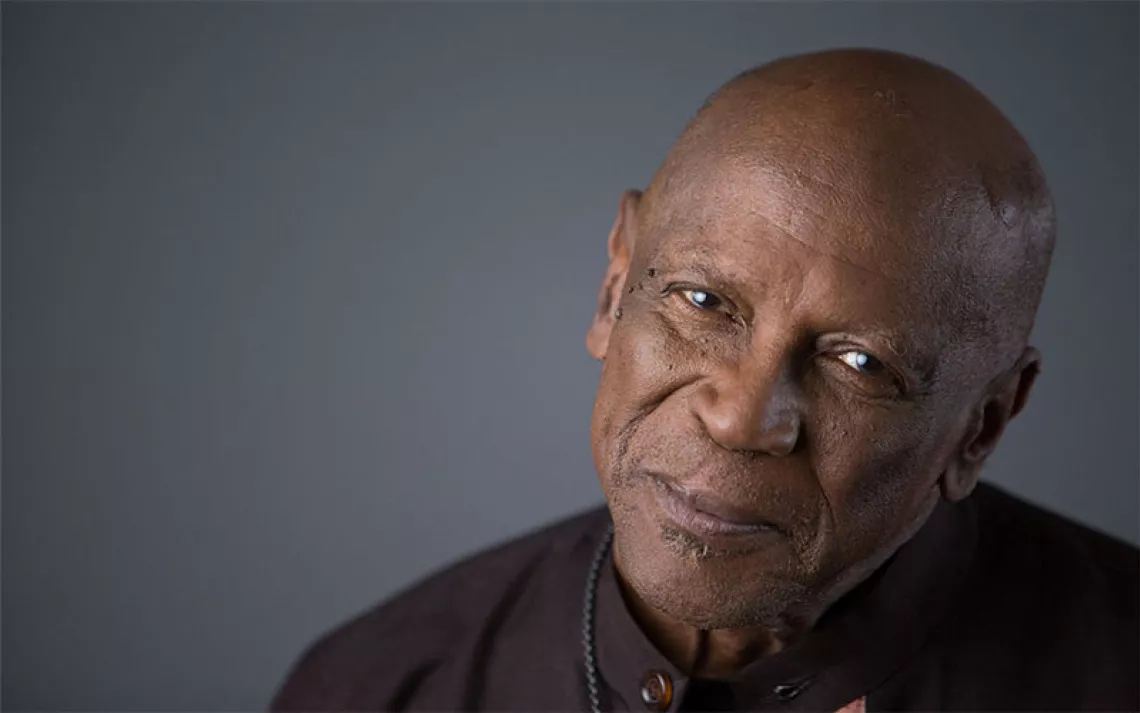

Tiger Mountain Foundation

When Rodney Smith’s uncle invited him to go to Sedona for a hike, Rodney, who is Black, said to himself, “Hiking? That sounds like something white people do.”

Smith went on the hike anyway. And it changed his life.

“I loved everything about it. I loved the scenery. I loved being outdoors. I had that wonderment of a kid.… I said, ‘This is my new thing,’ and I got out and started hiking on my own.”

This was following Smith’s release from prison in October 2021, after serving nine years on a 12-year sentence. He said, “I was forced to reconsider everything about my life, about my thinking, about the man I was and the man I wanted to become. I realized that a lot of what I had been doing was because it was expected, and it was what everyone else was doing. I hadn’t really figured out who I was and when I got out, I told myself I was going to start trying new things.”

He did start trying new things. In addition to taking up hiking, he started eating a plant-based diet—partially inspired by the story of Shadrach, Meshach, and Abednego from the Bible, who “looked healthier and better nourished” after 10 days of eating only vegetables than any of the young men who ate from the king’s table. On his ninth day of eating vegan, Smith was in line at a store, describing to someone how he felt “brighter and more energized” from his diet. A woman overheard and invited him to a community garden in South Phoenix, where Smith is from.

Again, Smith thought to himself, “This couldn’t be for me.” He said, “Gardening seemed like something for Martha Stewart … a suburban soccer mom activity.”

But when he arrived at the garden, he was immediately overwhelmed by the beauty and the connection he felt.

When Smith received his prison sentence, he did not cry. When he was inside and his father and both his grandmothers passed away, he did not cry. When he opened himself up to the connection with nature he felt in the garden, run by Phoenix’s Tiger Mountain Foundation, he finally cried.

“I’ve heard, ‘If you’re not crying, you’re not healing.’ I found a lot of healing in the garden. That feeling of connection made me say, ‘Oh my gosh, I feel like this is exactly where I’m supposed to be.’”

Now, Smith does community outreach for the Tiger Mountain Foundation, which works to empower communities through shared-use community gardens and other cultivated "spaces of opportunity." And he volunteers with his church’s Adventurers Club, part of the church’s youth ministry.

When Smith left prison, he felt like he could not go back home to South Phoenix, a particularly under-resourced part of the city, because there was nothing good there for him. Now he says, “With the garden spaces I work in, I don’t leave South Phoenix … and I am one of the community leaders helping to provide resources and opportunity to people who are like I was. I see people come to the garden and shed those tears just like I did. I see people struggling with anxiety and depression and addiction. They come to the garden and they find tranquility and peace. People find their sobriety in the garden; people find their purpose in the garden.”

We know that many people of color, and especially Black people, face unique barriers to enjoying nature. We often have less access to parks and green spaces due to where we live. And we face discrimination. You might recall the story of Christian Cooper, the Black bird-watcher who had the police called on him for simply requesting that a white woman leash her dog—which she was legally required to do—in New York’s Central Park. The gravity of that racist incident, in which the woman who called the police lied and said Cooper was threatening her, was driven home by George Floyd’s murder at the hands of the police in Minnesota later that same day, Memorial Day 2020.

For all the barriers Black people face, we should not let social stigmas and stereotypes infect our own minds and keep us from the benefits of nature and being outdoors. That is one reason Rodney Smith’s story is so important. It speaks not only to the healing power of nature but also to the power of challenging absurd stereotypes about where different kinds of people “belong.” Rodney Smith stepped outside his comfort zone to challenge stereotypes that said nature and outdoor activities were not for people like him.

There are opportunities to connect with nature everywhere in the country, even in big cities. For example, the Chicago Park District’s Outdoor and Environmental Education Unit has nature programs for all ages that include camping, fishing, and gardening. Its Nature Oasis program provides outdoor experiences and environmental education to nearly 18,000 city residents a year. Another option might be finding a local community organization like Phoenix’s Tiger Mountain Foundation or connecting with an outings group through your Sierra Club state chapter or other environmental organizations.

And thanks to important federal initiatives, like the US Department of Agriculture’s $1 billion urban forestry investment to expand access to trees and green spaces (made possible by President Biden’s Inflation Reduction Act), even more opportunities could be on the way.

The Magazine of The Sierra Club

The Magazine of The Sierra Club