In the Nation’s Asthma Capital, a Battle Over Biomass Rages

A Massachusetts bill classifying biomass as renewable reignites a decade-old fight

Photo courtesy of René Théberge

When Tanisha Arena thinks of the proposed biomass facility in Springfield, Massachusetts, she remembers a recent fire in a nearby trash incinerator that blanketed her neighborhood in smoke. That smoke was the last thing her city needed, she said. It was October, in the middle of allergy season and a respiratory pandemic, in the asthma capital of the United States.

When Arena remembers hiding from that smoke, she imagines a biomass incinerator burning wood in her backyard. Her community cannot handle any more pollution, she said.

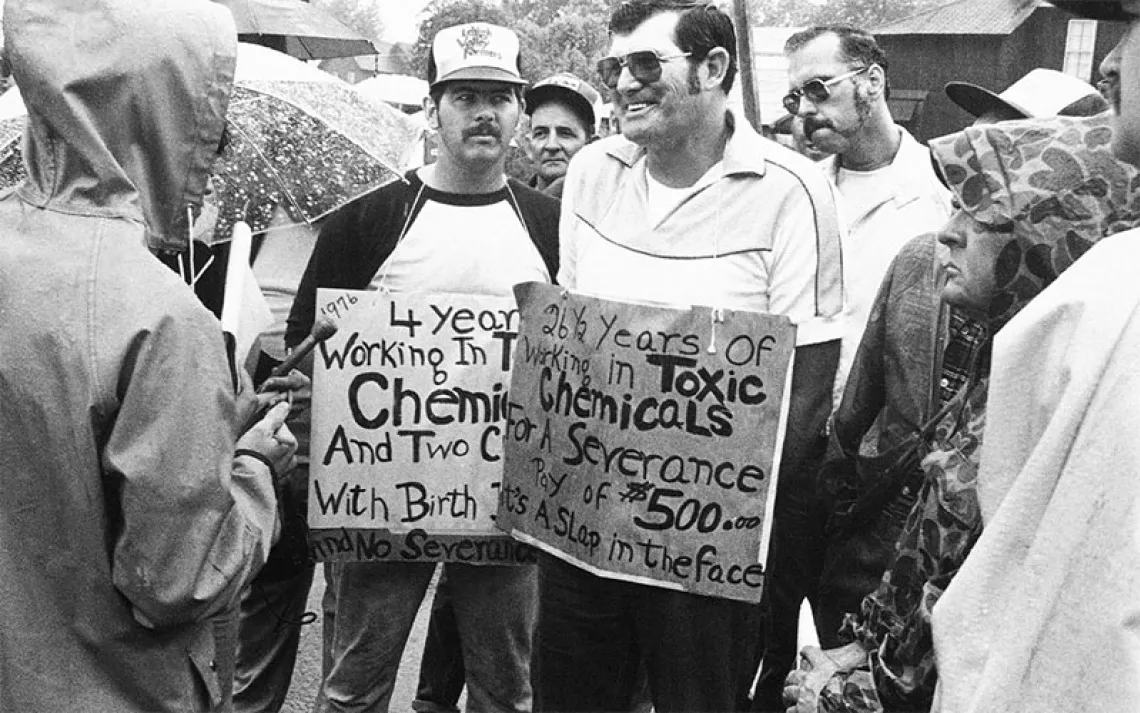

Arena is the executive director of the Springfield group Arise for Social Justice, which has been fighting the biomass plant—proposed by Palmer Renewable Energy—for over 10 years. Now, language in a Massachusetts House bill could make biomass eligible for certain renewable energy credits, potentially paving the way for the incinerator's construction.

With a few weeks left in the legislative session, local activists are circulating a petition with almost 7,000 signatures.

“We’ve protested, marched, written letters. The Springfield climate justice coalition has been making phone calls, drafting letters to the editors to say we don’t want this here,” Arena said. “Our message is clear, but there is this push to not let this plant die.”

Palmer Renewable Energy did not respond to multiple requests for comment.

Critiques of biomass center on two major impacts: environmental health and human health. Activists in Springfield first challenged the plant to protect the latter: the health of their community.

In the Massachusetts Environmental Justice Viewer map, Springfield is a patchwork of color. Each color indicates a reason why the Massachusetts government dubbed that neighborhood an “environmental justice population.” Nearly all of Springfield qualifies for this classification, by minority population (at least 25 percent of residents identify as a race other than white), income level (median household income is 65 percent or less of the statewide median), and “English isolation” (at least 25 percent of households have no adults who speak English well), or some combination of those factors.

In Springfield, a fifth of residents are Black, and nearly half are Latino. There’s a large Puerto Rican population for whom English is a second language. Nearly 30 percent of the city is in poverty. Compared with the state of Massachusetts, Springfield has low household income, low educational performance, and high unemployment. Hampden County—of which Springfield is the county seat—did not have the highest rates of COVID-19 in the state, but it did have the highest rates of COVID-19 deaths.

Besides the demographic vulnerabilities, Springfield has a geographic one. The city sits in a valley, a six-lane highway running through it. Air pollution concentrates in that valley, making it harder for residents to breathe. That’s part of the reason why, for the second year in a row, the Asthma and Allergy Foundation of America named Springfield the number one asthma capital in the United States.

“Where do they want to put a biomass plant? It's not an affluent community, not in places where there are predominantly white people. It's only in communities where there are Black and brown people,” Arena said. “This is not just about a singular biomass plant.”

What it’s about, Arena said, is a continued environmental assault on communities of color. Springfield has the highest number of asthma-related emergency room visits in the nation.

The biomass incinerator, if built, would release nitrogen compounds into the air. Dr. David Robertson, an allergist and immunologist based in Springfield, said that those compounds can contribute to ozone pollution. High ozone concentrations enhance the risk of developing asthma. Particulate matter can trigger asthma attacks.

Dr. Robertson, along with the experts at AAFA, are vocally opposed to the proposed biomass plant in Springfield. It adds burden to an already overburdened community, they said. According to their recent report on asthma disparities, Black Americans are already 1.5 times more likely to have asthma than white Americans, and three times more likely to die from it. Managing asthma—buying prescriptions, visits to the doctor—is expensive, and can be challenging to those experiencing poverty or with poor access to health care.

Activists say that Springfield should be working to decrease pollution in the city, not add a new plant. Even without the concerns about community health, there are raging debates over whether biomass is truly renewable.

Biomass power has been touted as a “bridge fuel”—one to take us from reliance on fossil fuels to a carbon-free economy. Most environmental groups are skeptical of calling it renewable, though. It emits three times as much carbon as natural gas and 1.5 times as much as coal. Proponents argue that trees regrow, sucking up any carbon released by burning them. That process takes decades, however, and requires that biomass companies follow sustainable logging practices.

“Even if you buy the arguments made about ensuring that the trees grow back and capture the carbon, they do not do so in any time frame that matters,” said Massachusetts representative Denise Provost, a vocal opponent of biomass power.

With so much opposition, many in Springfield assumed that the plans for a biomass incinerator were dead. Although Palmer Renewable Energy won its most recent legal battle over permitting, it didn’t start construction for years. The community figured that any financial incentives had dried up.

Then came the new climate bill.

The language in question, which classifies biomass as a “non-emitting source,” is one clause in a large, ambitious piece of legislation. The bill sets out to create “next-generation” climate policy in the state, including the statewide goal for net-zero emissions by 2050. In service of that goal, cities are required to source an increasing amount of their energy from renewable sources over the next 30 years. If this language makes it to law, cities will have greater incentives to purchase biomass power, propping up the industry.

Right now, two versions of the bill are on the table: the Senate version (which does not classify biomass as renewable) and the House version (which does). The bills are in conference committee, where legislatures are working to resolve the differences between them.

Activists in Springfield fear that creating incentives for biomass power will drive the proposed plant toward construction. Long-time activists call the Palmer plant a “zombie project.” The battle has lasted so long that Jesse Lederman, who began as an activist with Arise, is now a city councilmember.

“The legislative issue is about whether or not it is appropriate from a scientific perspective for this to be classified as renewable,” Lederman said. “Scientifically, we know that burning wood for energy is not a renewable practice.”

Both local and state legislators opposed to the inclusion of biomass in the climate bill are concerned that it would lead to more biomass incinerators throughout Massachusetts.

“Instead of investing in that future around wind and solar, which creates a lot of jobs, we’re going to dump this dirty wood-burning power plant in the middle of a low-income community in Springfield?” Massachusetts state senator Eric Lesser said. “My constituents will not stand for that. I will not stand for that.”

The Magazine of The Sierra Club

The Magazine of The Sierra Club