Mythical Figures Probe the Future in “Appleseed”

Sierra reviews Matt Bell’s latest novel

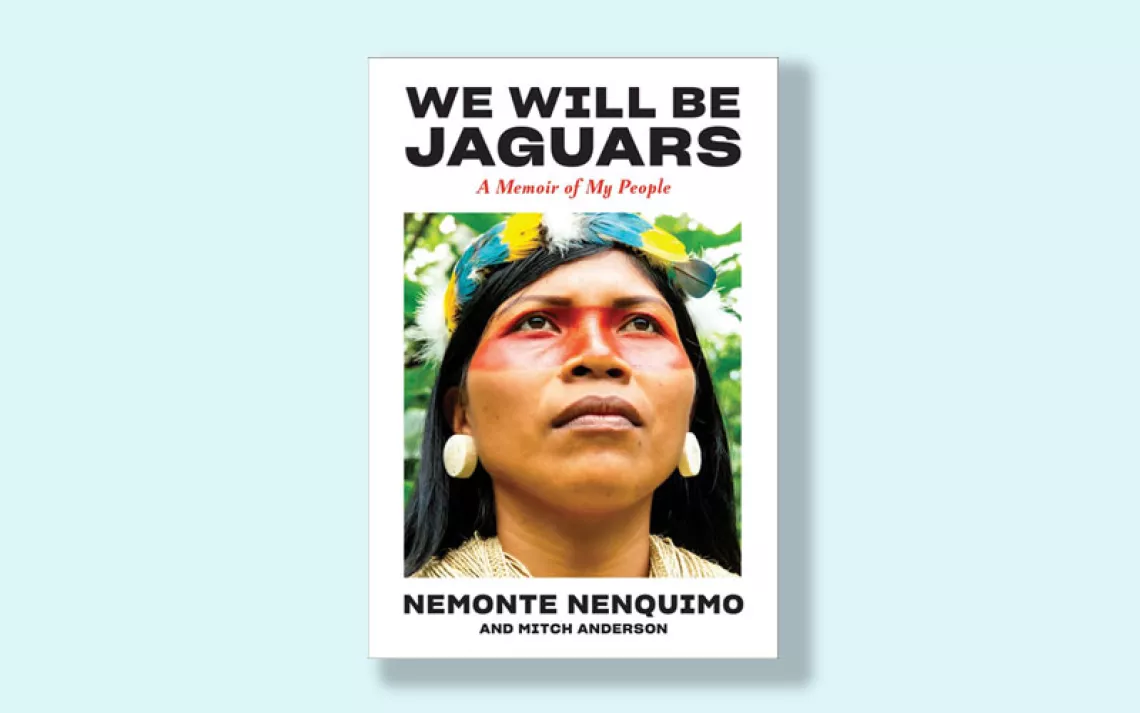

Courtesy of Jessica Bell

Matt Bell is nothing if not ambitious. In his new novel, Appleseed (out today from HarperCollins), the author of Shudder and In the House Upon the Dirt Between the Lake and the Woods alternates between three storylines. The novel addresses climate change, catastrophe, and rebirth from three very different angles, centuries, and technological eras.

One plot chronicles the peregrinations of two siblings in late-18th-century America. Chapman and his brother Nathaniel forge their way across the American Midwest, building orchards and planting apple trees in hopes that they will be paid for the efforts upon their return. The story sounds familiar, evoking a cheerful barefoot man with a pot on his head–something out of a bedtime story or a Midwestern historical landmark.

Matt Bell's version of Johnny Appleseed, however, progresses in a more peculiar fashion. His Chapman character is rendered as only half-human. The other half? A faun outfitted with horns and hooves, with roots that extend back to the mythic times of Orpheus and Eurydice, whose marriage feast was ruined by a drunk and lascivious satyr. Desperately lonely, he wishes to be wholly human like his sibling, but Chapman can't escape his hybrid nature.

Another plotline brings us to the latter third of the 21st century, in which one mega-corporation, Earthtrust, controls the planet's food supplies, bioengineering new crops that are hardy and bountiful but tasteless and tame. A Sacrifice Zone is created across the West and Midwest, with refugees pushed East to work for Earthtrust, the ultimate monopoly. Crops are raised, harvested, and distributed by members of the Volunteer Agricultural Communities—very cheap labor teetering on the edge of slavery.

Another plotline brings us to the latter third of the 21st century, in which one mega-corporation, Earthtrust, controls the planet's food supplies, bioengineering new crops that are hardy and bountiful but tasteless and tame. A Sacrifice Zone is created across the West and Midwest, with refugees pushed East to work for Earthtrust, the ultimate monopoly. Crops are raised, harvested, and distributed by members of the Volunteer Agricultural Communities—very cheap labor teetering on the edge of slavery.

John, the man partially responsible for Earthtrust's dominance, is now on an undercover mission of sabotage, armed with nanobees he created to replace extinct pollinators. John is determined to prevent his former lover and Earthtrust cofounder, the unpredictable Eury Mirov, from attempting to cool the earth's atmosphere, just as the Pinatubo volcanic eruption had decades earlier, when it spewed 20 million tons of sulfate aerosols and lowered global temperatures by half a degree Celsius.

Eury has big ambitions, and she doesn't let much get in her way. Bell writes, "But after the global economic collapse, the wars everywhere abroad and the Secession and the Sacrifice at home, the worsening climate disaster, and the collapse of the worldwide food supply? Maybe now Eury didn't need anyone's permission, for anything."

Finally, a thousand years after Earthtrust's founding, when most of the planet has become a ball of ice, a lonely watchman known as C-433 embarks on a mission from atop a glacier, determined to find other forms of life. The present C is its 443rd iteration, still able to recycle itself, however imperfectly.

Deep in a crevasse, C-443 unearths evidence of a lost civilization as well as the remnants of an ancient tree. Caught in an accident that would kill anyone else, C-443 and the tree go into a recycler together, undergoing death and a 3D-printed resurrection.

Appleseed starts slowly, its triune structure requiring patience and faith on the reader’s part that Chapman, John, and C-443 will prove equally interesting. Once the narrative gathers momentum, much of the fun of the novel comes from watching the connections accumulate between the various threads. Themes repeat across time: economic equity, manifest destiny, action transformed by mythology, environmental degradation, shifting power dynamics.

Chapman represents the bucolic past, a pastoral demi-god directly in tune with nature. John's story is set within sight of the present day, in which humankind makes a last-ditch effort to save itself via technology. Part flesh, part plant, part machine, C-433 trudges through the near-distant future, carrying samples of the past—of all its plants and animals wiped out by humanity.

In a novel suffused in loss, Chapman's story of Western expansion by foot is especially moving. The faun desperately wants to separate himself from his untamed nature, going so far as attempting to chop off his horns (this accomplishes nothing beyond causing himself more physical pain). He watches as his brother ages—Nathaniel grows ever more bitter that their years of travel have wrought nothing but poverty, their quixotic quest having cut him off from human connection.

The parts set in the near future have a welcome cyberthriller edge to them. John and Eury are well-matched opponents—she is adamant in her righteousness, he, unsure of his ability to stop her plans. Unlike Eury, he has his doubts about travel to other planets, and in the geoengineered manipulation of the stratosphere to lower temperatures.

Bell makes clear that climate catastrophe has drastically altered the world, while his characters struggle to contend with their new realities.

Grappling with his participation in the establishment of Earthtrust, John asks himself, "Isn't it a crime to take a world from someone, no matter how wrong that world is, if you can't guarantee a better world to come?”

C-443 is a walking experiment in biotechnology as he trudges toward promised revelation. His body becomes infected with "blackspot," becomes more vegetable than flesh. The transformation is messy: "He coughs until his eyes water, he wipes snot and drool from his broad lips with the back of his hand, leaves yellow mucus hardening blue fur."

References to mythology and folklore weave throughout Appleseed. Johnny Appleseed, of course, is the central reference, and more than one character wishes to eat from the Tree of Knowledge, but the "Song of Orpheus" repeats itself throughout the narrative. Eury takes an opportunity in the underworld to lecture John: "Keep your eyes on the future." "Don't look back" is a fitting warning for Chapman, John, and C-433 alike.

Central to the third futuristic narrative is the "printer" technology that allows for the recycling and resurrection of C-433 again and again. He is granted a tortured form of immortality as his body and memories are taken apart and reconstituted.

With its unusual structure, its recursive approach to characterization, and its fondness for esoteric details, Appleseed is sometimes reminiscent of the work of David Mitchell, author of Cloud Atlas and The Bone Clocks.

Bell possesses a similar virtuosity and versatility, a willingness to stray from the path of the expected and wander off into the realm of the fantastic. Thought-provoking and accomplished, his new novel acknowledges its debts to climate fiction and demands that readers examine the implications of humanity’s relationship with the natural world.

In Appleseed, Bell asks a new set of intriguing questions about what might constitute the future of the world—and who or what will be left to experience it.

The Magazine of The Sierra Club

The Magazine of The Sierra Club