Montana Youths Prepare for Trial in Major Climate Case Against the State

Landmark lawsuit alleges Montana’s government contributes to climate change by promoting a fossil-fuel-based energy economy

A BNSF oil train rolls through Whitefish. | Photo by Greg Lindstrom/Flathead Beacon

This article was originally published by The Flathead Beacon.

Twenty days before the first constitutional climate change case was set to go to trial, attorneys for the state of Montana succeeded in drastically narrowing the scope of the lawsuit after a judge dismissed claims against a now-repealed state energy policy.

Filed in March 2020, the lawsuit, Held v. Montana, was brought by 16 youth plaintiffs from across Montana who allege the state has violated their constitutional right to a clean and healthful environment. The complaint focuses on two statutes—provisions of Montana’s state energy policy, which explicitly promotes the use of fossil fuels, and an amendment to the Montana Environmental Policy Act (MEPA), which prevents the state from considering how the state’s energy economy contributes to climate change.

Rikki Held is the lead plaintiff in the constitutional climate change lawsuit Held v. Montana. | Photo courtesy of Rikki Held

In April, the Legislature passed House Bill 170 repealing the State Energy Policy, clearing a path for Montana Attorney General Austin Knudsen, representing the state, to file a motion to dismiss claims based on that statute as a matter of mootness.

During hearings on the policy’s review, Republican Governor Greg Gianforte’s natural resources policy advisor, Michael Freeman, told legislators Montana would still “have an energy policy. It is an all-of-the-above policy,” which plaintiffs’ attorneys interpreted as signaling no change to the state’s fossil-fuel first approach and, therefore, did not change the merit of the complaint.

But on May 23, Lewis and Clark County District Court Judge Kathy Seeley agreed with the state, writing that the only relief she could have offered would have rolled back the statute, which the state legislature already did.

However, Seeley stayed firm on her decision to allow the case to proceed to trial, which was a landmark victory for climate change advocates when she initially set a bench trial in 2021. In the recent court filing, Seeley wrote there are five facts in dispute to be taken up at trial, including "whether climate impacts and effects in Montana can be attributed to Montana’s fossil fuel activities."

Even in its narrowed scope, the case’s full weight rests on a constitutional underpinning—whether the legislature’s cumulative reforms to MEPA violate Montana’s constitutional mandate that “the state and each person shall maintain and improve a clean and healthful environment in Montana for present and future generations.” This provision, inserted into the state’s governing document during its 1972 drafting, is the basis for the bellwether environmental trial.

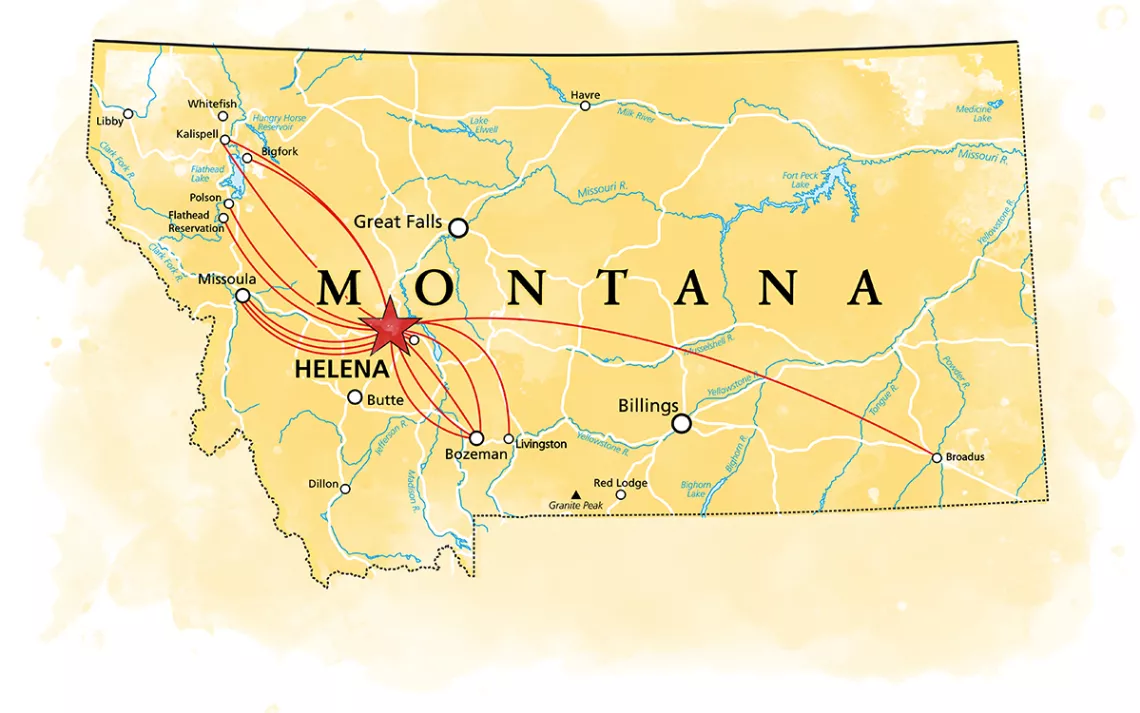

Map showing location of plaintiffs in Held v. Montana with Helena, site of the upcoming trial, indicated. | Graphic by Flathead Beacon Productions

“Governments need to make broader changes, and quickly, with the best available science in order to protect our rights,” said Rikki Held, 22, the eldest plaintiff for whom the lawsuit is named. “A clean and healthful environment is a basic necessity everyone has, and we’re talking about not just us, now, but future generations.”

In addition to carving out the lawsuit’s claims centered on the state energy policy, attorneys for the state have launched efforts to dismiss the remaining claims based on MEPA, as the legislature amended the law to ban state agencies from considering climate change during environmental review, arguing it's a "wholly new statute."

Now is the time for environmental journalism.

Sign up for your Sierra magazine subscription.

“The main part of this case has now been thrown out, and what’s left of the case should also be dismissed,” according to Emily Flower, a spokesperson for Attorney General Austin Knudsen. “This entire case has been nothing more than a publicity stunt spearheaded by an out-of-state special interest group. We believe this political theater will come to an end soon.”

Held and her co-plaintiffs reject any suggestion that the case represents a publicity stunt.

“As youth, we are exposed to a lot of knowledge about climate change. We can’t keep passing it on to the next generation when we’re being told about all the impacts that are already happening,” Held said. “In some ways, our generation feels a lot of pressure, kind of a burden, to make something happen because it’s our lives that are at risk.”

The case is set to proceed to a 10-day bench trial beginning June 12 in Lewis and Clark County District Court, where both sides will present evidence and testimony for the court to determine its legitimacy.

Held v. Montana is not the only climate case in which environmental attorneys have been laying the groundwork for litigation. The Sabin Center for Climate Change Law currently tracks 2,424 climate-change-related cases in the world, 1,591 of which are filed in US jurisdictions. Our Children’s Trust, an Oregon-based nonprofit law firm representing the Montana youth, has filed similar legal actions in all 50 states that have included children as plaintiffs. Young people are slated to experience the worst of the accelerating crisis in the coming years, with a 2021 UNICEF index showing half of the world’s 2.2 billion children live in countries facing extremely high risks of climate disaster.

A satellite view of the toxic Berkeley Pit, a former open pit copper mine that is currently one of the largest Superfund sites. | Photo by NASA

Other youth-led climate change cases in the United States, including one filed against the federal government, have been derailed before proceeding to trial, setting Held up as a landmark case. (On April 6 a judge in Hawai'i ruled a youth-led climate case against that state's Department of Transportation will proceed to trial this fall, and on June 1 a federal judge ruled the case Juliana v. United States will also proceed to trial.) In a 2011 Montana lawsuit, Our Children’s Trust directly petitioned the Montana Supreme Court to declare that Montana has a duty to protect and preserve the atmosphere. The court rejected the petition, stating that there was no reason the youth plaintiffs couldn’t follow the normal channels of litigation through a lower court, followed by an appeal to the Supreme Court. To that end, Held was filed in Montana’s First Judicial District Court with the intent of establishing a court record that can, if needed, be appealed to the Montana Supreme Court, according to attorneys for the plaintiffs.

The 16 youths named in the lawsuit now range from ages six to 22 and hail from communities from across Montana, from Broadus, to Bozeman to Bigfork, and collectively represent a wide range of lived experiences in which climate change has figured prominently as a maleficent force. The named defendants include Montana Governor Gianforte, the Montana Department of Environmental Quality (DEQ), Department of Natural Resources and Conservation (DNRC), Department of Transportation (MDT) and Public Service Commission (PSC).

Nate Bellinger, one of the attorneys for the nonprofit law firm Our Children’s Trust representing the plaintiffs, describes the current case as standing on three main pillars of evidence.

Mine work at Westmoreland’s Rosebud Mine near Colstrip. | Photo by Alexis Bonogofsky

“You have these two things working in conjunction where the state's aggressively promoting fossil fuels and at the same time ignoring how those fossil fuel projects are contributing to climate change,” Bellinger said. “We also have really strong evidence about the ways in which climate change is already impacting Montana's environment and Montana citizens.”

All three of those points tie directly back to Montana’s constitutional right to a clean and healthful environment, the legal argument that can take on what plaintiffs’ co-counsel Roger Sullivan calls the “fossil fuel paradigm.”

Sullivan, an attorney with the Kalispell firm McGarvey Law, has spent four decades litigating environmental lawsuits in Montana. What sets those cases apart from Held, he said, is their piecemeal approach to holding fossil fuel-reliant projects accountable one state-sanctioned permit at a time, which, he said, is “akin to putting your finger in the dike.” They don’t carry the weight of a constitutional case like Held, Sullivan said, which takes aim at the cumulative impacts of the fossil-fuel industrial complex and the systems in place promoting it.

Skiers navigate the trees in the Canyon Creek backcountry ski area in Whitefish. | Photo by Hunter D’Antuono/Flathead Beacon

“Each of those aggregate acts has the consequence of spewing these greenhouse gases, diminishing the quality of the environment here in violation of the plaintiffs’ constitutional rights,” Sullivan said. “We just have one atmosphere, so a ton of carbon in Montana is just as damaging as a ton of carbon being placed into the atmosphere somewhere else in the world.”

Montana has a long history with extractive industries, going back to the Copper King mining barons who commandeered much of the state’s economic and political authority in the 19th and early-20th centuries. By recognizing the enormous political power wielded by those titans of industry, as well as the degradation of Montana’s environment at their hands, 100 delegates helped craft some of the nation’s most unassailable environmental protections during the rewriting of Montana’s constitution in 1972.

Montana is still entrenched in the fossil fuel industry despite decades of understanding its broad impacts on the environment and the climate, according to Anne Hedges, director of the Montana Environmental Information Center, and an expert witness for the plaintiffs in the climate case.

Roger Sullivan, an attorney with McGarvey Law in Kalispell, will argue for the plaintiffs in court. | Photo by Isaac Miller via Flathead Beacon

Montana has the nation’s largest coal reserves, accounting for one-third of all recoverable coal deposits, according to the US Energy Information Administration, and the state is the sixth-largest coal producer in the country.

Going back more than 50 years, state officials have raised concerns about the coal industry, according to Hedges, who is expected to provide key testimony during the trial. In her 30-page expert opinion report, she cites former governors and agency leaders warning of the environmental consequences of coal and other fossil-fuel-reliant developments.

“For the past five decades, the state of Montana has known that continuing to promote coal as an energy resource came with great risk for Montana’s environment, natural resources, economy, and residents, and that viable alternatives exist,” Hedges wrote. “Defendants to this day continue to push for an increase in the utilization and development of coal, oil, and gas, even as the dangers posed by fossil fuels and climate change have become irrefutable.”

Lander and Badge Busse on a hill near their home overlooking Kalispell on May 3, 2023. | Photo by Hunter D’Antuono/Flathead Beacon

In 1993, the legislature adopted the State Energy Policy, which initially outlined goals to “promote energy conservation, production, and consumption of a reliable and efficient mix of energy sources that represent the least social, environmental, and economic costs.” In 2011, the legislature amended the energy policy by adding five provisions explicitly promoting an expansion of the fossil fuel economy; although the Held case initially challenged those provisions, they’re no longer relevant for the purposes of trial following Seeley’s 11th-hour order.

“I have been opposing fossil fuel projects in Montana for 30 years,” Hedges wrote. “In my opinion, the only thing that will fundamentally alter the state’s historic and ongoing energy policy of prioritizing the development and use of fossil fuels is a court order declaring that policy unconstitutional.” She added that, in her experience, she is unaware of a single example of state agencies denying an environmental permit to a fossil fuel company.

In a recorded deposition, DNRC Forestry-Trust Lands Division Administrator Shawn Thomas concurred, stating he was unaware of the department denying a coal lease permit in at least two decades.

Additional expert witnesses for the plaintiffs include Steve Running, a global ecology and climate change researcher who contributed to the 2004 Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) report. In an expert report co-authored with Cathy Whitlock, a climate scientist with Montana State University, Running discusses the current trends and future projections of the state’s ecological systems and how they’re effected by increasing levels of greenhouse gas emissions.

“Every ton of fossil fuel that Montana extracts or consumes makes it harder to return to 350 ppm of CO2 in the atmosphere,” Running wrote in the report, referencing a commonly accepted scientific goal for an upper limit of CO2 levels in the atmosphere. “When you are already in a dangerous hole, you stop digging.”

Running’s and Whitlock’s report also states that Montana’s level of greenhouse gas emissions is higher than the national average “exacerbating the current Earth energy imbalance, and thereby locking in additional global warming and the attendant climate impacts.”

Based on witness testimony and pre-trial depositions, the state is expected to argue that Montana’s impact on climate change is minuscule, that halting fossil fuel production would not eliminate the physical effects of climate change in Montana, and that any psychological impacts felt by the plaintiffs are a result of “apocalyptic and misleading rhetoric,” according to climatologist Judith Curry, an expert witness for the state.

Curry, a former Georgia Institute of Technology department chair, is known for rejecting mainstream scientific consensus on the significance of human contribution to climate change, and instead largely attributes shifts in global climate to natural variability, according to her expert report.

Another expert expected to testify for the defense, former MSU professor Terry Anderson, who specializes in economics and the environment, states in his expert report that, “it does not make sense for any state to undertake policies to reduce CO2 emissions.”

“Producing that lump of coal in Montana has an effect on the state’s economy,” Anderson wrote. “Maybe you have less water in the stream for your fishing or less snow to ski on, but you also have a job.”

At trial, attorneys for the plaintiffs will argue their clients have suffered “significant and physical manifestations of an infringement of their constitutional right to a clean and healthful environment,” as they allege in their complaint.

The 108-page complaint includes four requests for declaratory relief and five requests for injunctive relief along with attorneys’ fees. In her 2021 ruling that allowed the case to proceed to trial, Seeley dismissed four of the injunctive requests, including a requirement for the state to prepare a complete accounting of Montana’s greenhouse gas emissions and develop a remedial plan to reduce emissions. But Seeley left intact a request by plaintiffs for the state to stop subjecting the Montana youth to the state’s energy policies and the climate change exception to MEPA.

Even with the lawsuit partially dismissed, Bellinger is hopeful for two favorable results from Seeley: a ruling that existing laws are unconstitutional, and an order enjoining Montana from approving new permits for fossil fuel development without consideration of climate change as a factor.

Ongoing defense efforts to have the case thrown out cited an end-of-session bill, House Bill 971, which was among the most controversial during the 2023 legislative session. The measure amended MEPA to preclude agencies from considering greenhouse gas emission or climate change impacts during environmental reviews of large projects.

However, Seeley states in court filings that there appears to be a “reasonably close causal relationship” between the permitting of fossil fuel activities under MEPA, greenhouse gas emissions, climate change and its effect on the young plaintiffs.

During a pretrial hearing, attorneys for the plaintiffs pushed back against arguments that the new MEPA language changed the merits of the lawsuit.

“This bill was entitled, ‘an act generally revising the environmental policy act clarifying and excluding the use of greenhouse gas evaluations.’ That’s exactly what the agencies have already been doing,” Sullivan said. “This amendment does not substantively change anything and would just be a sinister move undermining the long-awaited rights of these plaintiffs to argue otherwise.”

Seeley concurred that she did not interpret the new MEPA amendment as “nearly as substantive” as the defendants.

Sullivan told the Beacon that in four decades of practicing environmental law, he’s never worked on a lawsuit in which defendants have launched such a concerted effort to fundamentally alter or restructure laws to prevent a suit from reaching trial.

“The uniqueness of the situation is that they were able to go in and surgically attempt to obstruct and obfuscate,” the facts of the case, Sullivan said.

Bellinger said the defendants’ efforts to challenge the lawsuit indicate how concerned they are about the consequences of the trial.

“They do not want all of this evidence to come out in court, and they don’t want to be required to take a position on climate science in a courtroom,” Bellinger said. “It’s a pretty thinly veiled effort to avoid a decision from the court about the constitutionality of their conduct promoting fossil fuels.”

Two of the plaintiffs, brothers Lander and Badge Busse, of Kalispell, were part of the 2011 lawsuit against the state and, 12 years later, will finally get their day in court to take the stand for their future.

“Every plaintiff involved in this case, we’re just normal kids at the end of the day, all doing their own thing, who saw an opportunity trying to get the word out and fight for the things they love,” Lander said. “I feel like we have a citizen’s duty to uphold the Constitution, so it doesn't really matter if we have people trying to disagree with us.... We're doing it for them as much as for the people who agree with us.”

Plaintiffs include Rikki Held of Broadus, who was the only plaintiff of age when the suit was filed, Mica Kantor of Missoula, Lander and Badge Busse of Kalispell, Kian Tanner of Bigfork and other youths from Missoula, Bozeman, Polson, Helena, Livingston and the Flathead Indian Reservation. The plaintiffs are represented by attorney Nathan Bellinger of Our Children’s Trust, as well as Roger Sullivan and Dustin Leftridge of Kalispell’s McGarvey Law and Barbara Chillcott and Melissa Hornbein of the Helena-based Western Environmental Law Center. Our Children’s Trust is an Oregon-based nonprofit public interest law firm that litigates a wide array of youth-based climate lawsuits.

This article is part of a series on the youth-led constitutional climate change lawsuit Held v. Montana, which goes to trial in Helena on June 12. The rest of the series can be read at mtclimatecase.flatheadbeacon.com. This project is produced by the Flathead Beacon newsroom, in collaboration with the Montana Free Press, and is supported by the MIT Environmental Solutions Journalism Fellowship.

The Magazine of The Sierra Club

The Magazine of The Sierra Club