An MLK Day Monument Wish List

These four sites reveal a fuller story of the civil rights movement

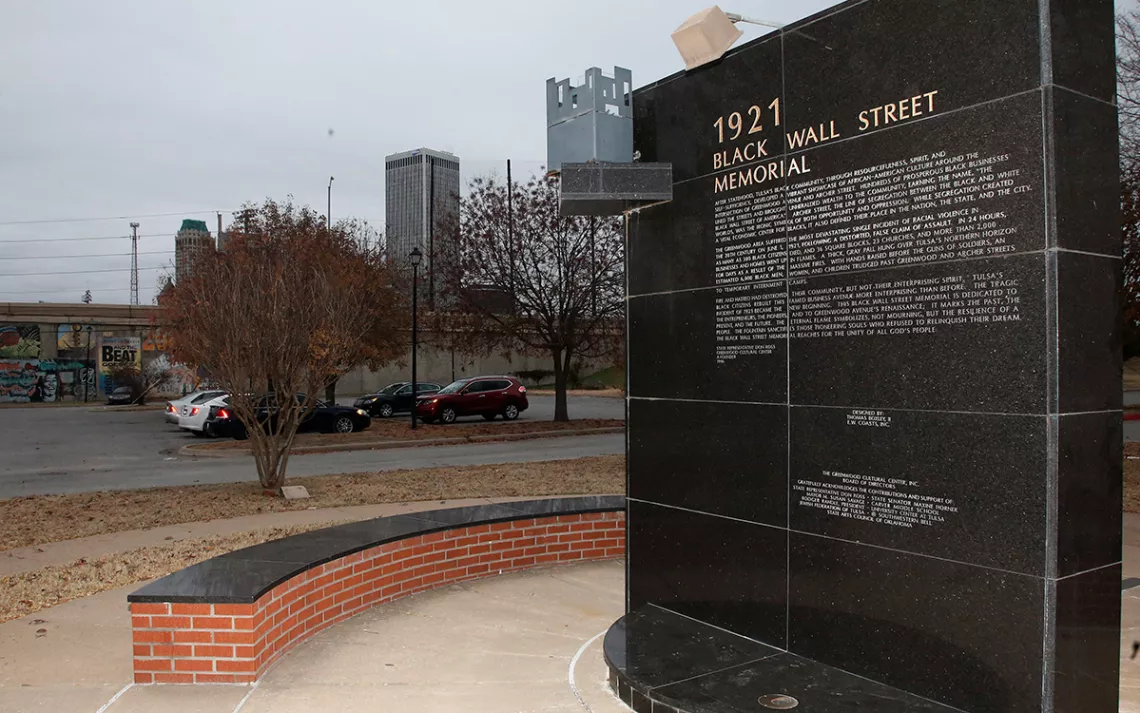

A once-prosperous section of Tulsa, Oklahoma, that became the site of one of the worst race riots in US history is attempting to remake itself again after decades of neglect. | Photo by Sue Ogrocki/AP

Beyond protecting incredible landscapes and critical habitats, the US national park system plays a crucial role in telling the story of this country and ensuring significant pieces of history and culture are preserved. But while the NPS holds immense storytelling power, fewer than a quarter of its sites acknowledge the histories of nonwhite people, movements, and cultures. Perhaps for that reason (among others), people of color are significantly underrepresented among NPS visitors.

This Martin Luther King Jr. Day, we’re calling on the federal government to employ the Antiquities Act—the president's power to designate historic landmarks and places of historic or scientific interest as national monuments—to commemorate more sites that will help ensure that US public lands reflect America’s diversity.

“Each new national monument adds a new chapter to the narrative our public lands tell," says Dan Ritzman, director of the Sierra Club's Lands, Water, and Wildlife campaign. "Each new site adds pages commemorating the legacies of the people and communities who came before us and who shaped this country and its landscapes. We need to maintain those legacies and make sure to tell those stories for the next generation.”

Similar to recent designations of the Pullman, Stonewall, and Hono’uli’uli National Monuments, the following proposed monuments would also highlight events in our country’s history that are too often forgotten. The stories of these four places honor people who forced the nation to face the reality of racism, and whose courage indelibly influenced the course of the civil rights movement and the ongoing fight for equality. Lifting up these stories will help NPS visitors continue to reckon with our past, and help enlighten ongoing dialogues about equity, inclusion, and the stories we tell on our public lands.

Springfield Race Riot Memorial

One of the most violent race riots in America’s history took place on August 14, 1908—and it’s one of which many are unaware. It occurred in Springfield, Illinois, the birthplace of Abraham Lincoln, in a state where many Blacks came in the early 20th century seeking refuge from racism in the South. Following rumors that a Black man had raped a white woman, a white mob attacked Springfield’s Black neighborhoods and lynched residents there. Beyond being symptomatic of the racism that pervaded the North, this act of terror caused $150,000 in damage and has had residual effects—today, Springfield is divided by railroad tracks, with wealthy whites on the prosperous west side and poorer Blacks on the east side, which never recovered from the devastation of the riots and its resulting wealth gap.

This violent episode also served as a catalyst for the creation of the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP), which aimed to be a voice for Blacks fighting to live in the United States. The NAACP continues to empower, educate, and encourage today. The NAACP, the Sierra Club, and many other grassroots and local organizations recently sent a letter to President Biden urging him to make the site a national monument, encompassing an archaeological site where the foundations of five burned houses and associated artifacts have been found, so that this history is never forgotten.

Tulsa Race Massacre Memorial

When a white mob targeted the Greenwood District of Tulsa, Oklahoma, in June 1921, they were attacking one of the country’s most prosperous Black business hubs and neighborhoods, known colloquially as “Black Wall Street.” The mob headed for the Greenwood District following an altercation at a jail, where Black supporters had assembled to protest the planned lynching of Dick Rowland, a Black shoe-shiner accused of assaulting a white 17-year-old elevator operator. Over two days, they killed an estimated 300 people and destroyed scores of businesses and residences, leaving an estimated 10,000 Black people homeless.

It was one of the deadliest terrorist attacks in the history of the United States. By the end of 1922, residents had largely rebuilt, but the city and real estate companies refused to compensate them. Many survivors left Tulsa, while residents who chose to stay in the city, regardless of race, largely kept silent about the terror, violence, and resulting losses for decades. The massacre was largely omitted from local, state, and national histories.

Last year, on the centennial of the massacre, the Sierra Club joined the Black-led movement in Tulsa to urge the Biden administration to designate the Greenwood District a national monument, so as to safeguard the historic place, celebrate Black success, and formalize recognition of this under-publicized atrocity in history books.

Emmett Till and Mamie Till-Mobley Memorial

Emmett Till was an African American teenager who grew up in Chicago. At 14, he visited relatives in the Mississippi Delta, where, in August 1955, he was kidnapped, tortured, and killed by white men after being accused of whistling at a white woman.

His mother, Mamie Till-Mobley, became a civil rights icon after his death. She sought justice for her child, demanding his casket be transported home and unsealed, and insisting his mangled corpse be shown to the world. Until her death in 2003, Till-Mobley devoted her life to seeking justice for her son, speaking publicly about racism and comforting other grieving families.

The National Park Service has been examining key civil rights sites in Mississippi for possible designation, such as the Tallahatchie County Courthouse in Sumner, which is where thousands of people flocked to see Till’s murderers stand trial and be acquitted, and which is now home to an Emmett Till Interpretive Center. They’re also considering designating the Roberts Temple Church of God in Christ in Chicago, where Till’s open-casket memorial service was held, drawing tens of thousands of people who responded to Till-Mobley’s outcry for the world to see what racists had done to her son.

Stone Mountain in Georgia

At a time when Confederate monuments around the country have come down, this carving into Stone Mountain—depicting Jefferson Davis, Robert E. Lee, and Thomas J. “Stonewall” Jackson on horseback—stubbornly lingers. Beautiful and bucolic Stone Mountain, 15 miles east of Atlanta, is a natural wonder turned Confederate memorial. We’d like to see this existing Georgia state monument reconceptualized

While intended as a military monument to fallen Confederates, Stone Mountain’s history is inextricably intertwined with the rise of the modern Ku Klux Klan. In 1915, a group of men—inspired by D.W. Griffith’s film The Birth of a Nation, which lionized the original Ku Klux Klan—ascended the mountain to burn a cross and resurrect the KKK. Afterward, the owner of Stone Mountain gave the Klan unrestricted access to the site for rallies and meetings, which they retained until the state purchased the site in 1958.

On July 5, 2020, 100 to 200 armed protesters came to Stone Mountain to call for the carving's removal—the protest location was chosen in part due to its significant Klan history. On August 15, 2020, the park administration closed its gates in reaction to a planned gathering of white nationalists, but a fight still broke out in downtown Atlanta between gatherers and counter-protesters.

While the Atlanta NAACP chapter and Georgia state representative and Democratic gubernatorial candidate Stacey Abrams have called for the carving’s sandblasted removal, describing it as “a blight upon our state,” Georgia law prohibits the memorial from being “altered, removed, concealed, or obscured in any fashion.” Ironically, Martin Luther King Jr. himself mentioned the monument in his “I Have a Dream” speech at the August 1963 March on Washington, when he proclaimed “let freedom ring from Stone Mountain of Georgia!”

Over the years, various ideas have been pitched to counter or contextualize the Stone Mountain memorial—one popular one was to install a permanent “Freedom Bell” to honor its significance in MLK’s landmark speech.

“We can reclaim this space for the diverse masses of people that not only reflect the state of Georgia but of the United States," says Lornett Vestal, senior campaign manager for the Sierra Club's Military Outdoors campaign, who works closely with the on-the-ground Stone Mountain Action Coalition to help contextualize the monument. "It’s why Sierra Club Military Outdoors chose Stone Mountain for our Hike for Peace. We wanted to take a group of diverse young people to a place to show the world that bigots, racists, and those filled with hate have tried to make it their monument of injustice, but the reality is this land is our land. It belongs to all people who call this place home. From the Indigenous peoples of the Cherokee Nation to the Muscogee to the Freedom Riders to little Black boys and girls living in the West End neighborhood of Atlanta learning about their hometown hero, Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. This land is all of our land. It’s time to reclaim it.”

In November, the Stone Mountain Memorial Association, the state entity that runs the site, announced it had contracted with an exhibition design firm, Warner Museums, to conceptualize and build a new “truth-telling” display about the history of the monument. “Monument: The Untold Story of Stone Mountain,” newly available for viewing on the Atlanta History Center’s website, tells a much more nuanced and complex story of Stone Mountain and hopefully serves as a way of remembering that which has been forgotten—or, perhaps more accurately, unspoken.

The Magazine of The Sierra Club

The Magazine of The Sierra Club