Meet the Adventurers Who Brave Glacial Caves in the Name of Science

Glacier Cave Explorers volunteer to study life beneath the ice

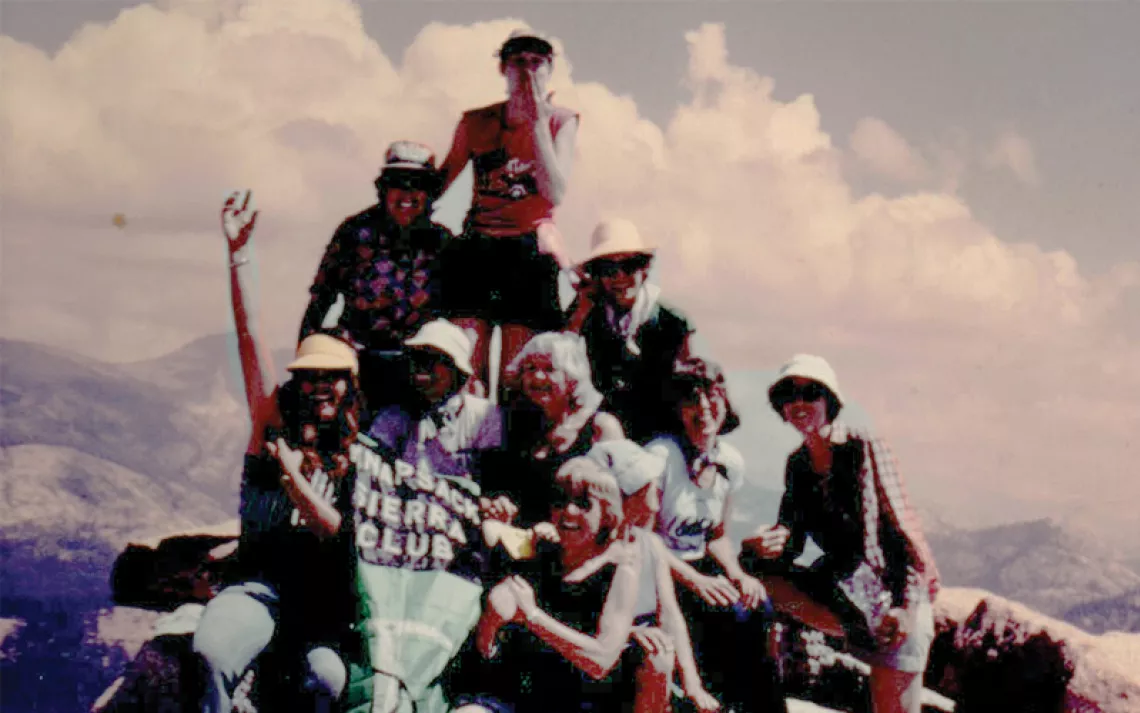

Photo courtesy of Brent McGregor

Eddy Cartaya and Brent McGregor have unearthed what might as well be another planet. It exists in the backyard of 6 million people, in areas frequented by scores of national park tourists each year.

In 2011, the two men founded Glacier Cave Explorers, a Pacific Northwest–based group of scientists and adventurers, all of whom probe, map, and study the extensive cave networks that lie beneath the glaciers on Mount Rainier and Mount St. Helens in Washington and Mount Hood in Oregon. These caves, formed by meltwater and volcanic steam, can answer questions about climate change, volcanology, and alpine rescue—and even about what life might look like on other planets. And expeditions to their ethereal, dangerous depths make for one hell of a thrill.

Before they learned of these glacier caves, Cartaya and McGregor had spent years exploring limestone caves and lava tubes. “There’s something especially alluring about a cave,” says Cartaya, who is a search-and-rescue volunteer, avid climber, law enforcement officer, and cave manager for the U.S. Forest Service. “When you see a hole and you can’t see the extent of what it harbors, there’s a draw to go in, as opposed to a mountain, where you can see the top.”

Eddy Cartaya, photographed by Katie Campbell

McGregor, a professional wood sculptor, was simply seeking a break from work when he started climbing mountains. “I was in my mid-40s, around the time most people are retiring from climbing,” says McGregor, now 65. “I just started summiting peaks—one after the other, more than once, different routes, different seasons, whatever. Once I had done that, I started looking underground.” In 2011, he happened upon a YouTube video that showed hikers at the entrance of a cave on Mount Hood’s Sandy Glacier and knew he (and his friend Cartaya) had to check it out. While McGregor is quick to note that he didn’t discover the cave he named Snow Dragon, he and the Glacier Cave Explorers have since 2011 mapped its more than 7,000 feet of passages.

That first trip into Snow Dragon ignited a new chapter in the two men’s caving careers. The multidisciplinary group they founded afterward—Glacier Cave Explorers is part of the National Speleological Society—has since undertaken expeditions to the ice-encrusted upper reaches of Mount Rainier, Mount St. Helens, and Mount Hood.

Courtesy of Brent McGregor

Every spring and summer, Glacier Cave Explorers dispatches teams of eight to 12 people up these mountains; some team members are researchers and others are mountaineers who help transport gear, mark routes, and ensure safety. Each mountain’s approach is different: On Mount St. Helens, equipment can be flown in via helicopter; Rainier requires a multiday climb with packs weighing 80 to 90 pounds. Mount Hood’s cave entrances can be reached via a half-day hike. Expeditions last from a few days to two weeks.

Though the researchers have visited each cave many times, they’re never sure what to expect.

“With limestone caves, you’ll see them grow a little bit if you wait around a thousand years,” Cartaya says. “But glacier caves change daily as the whole glacier moves down the mountain. Every time we go back it’s like going to a new cave. Waterfalls change positions. Different rooms have formed while others have gone away.”

The team approaches a cave’s entrance carefully. “Rocks are coming down from the surface and landing in piles at the entrance of the cave,” Cartaya says. “Sometimes getting in the cave is the most dangerous part, because you’re playing Russian roulette with these things raining down.”

Once inside, headlamps illuminate surreal surroundings: wind-scalloped walls glowing blue and green and sparkling like diamonds, meltwater lakes, waterfalls, ceiling holes called moulins, rooms hundreds of feet in diameter, ice stalagmites, and other bizarre formations. “It’s a magical place,” McGregor says.

Courtesy Tom Wood

It’s also a noisy one. “You’ll hear big rocks melting out of the walls or the ceilings and hitting the floor, or hundred-pound blocks of ice falling off the ceiling, hitting the floor, and ricocheting down the tube with a thunderous roar—kabaam!” McGregor says. “Almost every trip, I come out and have lost my voice because you have to yell so loudly.”

The Glacier Cave Explorers can’t spend too much time admiring the sights, though—they have to concentrate on the host of things trying to kill them: collapsing ceilings, unexpected floods, ice falls, crevasses, boulders the size of houses careening down passages, avalanches. That’s to say nothing of the gases—these are, after all, active volcanoes. The team carries rebreathers and gas monitors to track deadly levels of carbon dioxide, which can pool in invisible lakes below lighter, safer stores of oxygen. A simple fall can send someone into a lethal pool of carbon dioxide (the symptoms of this happenstance closely resemble those of altitude sickness). Meanwhile, volcanic fumaroles can exhale sulfurous gases unpredictably. “It’s a constantly changing environment,” Cartaya says. “Not just structurally but chemically.”

Mount St. Helens, which erupted in 1980 and 2004, is its own beast. “It’s not that high, but it’s basically like a nuclear bomb went off up there,” Cartaya says. “Everything is fractured, falling apart. There are boulders constantly falling down the crater, and it’s a very stressful environment to be in. The ground is literally moving beneath you.” St. Helens is also home to the lower 48’s only growing glacier, making it a particularly interesting destination for scientific study.

Sign up to receive Sierra News & Views

Get articles like this one sent directly to your inbox weekly.

With this action you affirm you want to receive Sierra Club communications and may vote on policy designated by the Sierra Club Board.

Courtesy Brent McGregor

Safety management and planning play a significant role, and so far, Glacier Cave Explorers have experienced no serious incidents. Cartaya emphasizes that theirs are not endeavors for amateurs or thrill-seekers—each team brings it own rescue and medical supplies and installs a field hospital outside the caves.

The research collected on these expeditions serves multiple purposes. The maps—which need to be updated annually as the caves change—can be used in rescue missions. Some scientists who join trips study rare microbial life, looking for so-called extremophiles that thrive in unlikely conditions. Their findings could provide context into what life might look like on Mars and Europa.

Expeditioning glaciologists look for changes beneath the ice that can lend new information about climate change (typical climate studies look at glaciers only from above). This data, especially from the dying glaciers on Mount Hood, can be helpful in predicting impacts on watersheds and other natural resources. “Glaciers are also paleoclimate archives,” Cartaya notes. The layers in a glacier—stripes that indicate seasons—are climatic snapshots dating to a glacier’s birth. The caves make those layers visible.

Of immediate concern is the question of whether these volcanoes are going to erupt. While the volcanoes are studied extensively for seismic activity, Cartaya says there are other, more silent indicators of potential disaster—and that they’re not all thoroughly understood or tracked.

“The ice on these volcanoes can react to changes in geothermal or hydrothermal activity in the mountain,” Cartaya says. “It can register changes that are not noticed by surface observations, changes that could signal a destructive event that’s not going to be advertised seismically.” These changes can point to structural instabilities in the volcano and may portend cataclysmic mudflows, called lahars, which can threaten nearby communities. “Like a wet sand castle, the mountain can blob over under its own weight and collapse,” Cartaya explains.

“The ice on these volcanoes can react to changes in geothermal or hydrothermal activity in the mountain,” Cartaya says. “It can register changes that are not noticed by surface observations, changes that could signal a destructive event that’s not going to be advertised seismically.” These changes can point to structural instabilities in the volcano and may portend cataclysmic mudflows, called lahars, which can threaten nearby communities. “Like a wet sand castle, the mountain can blob over under its own weight and collapse,” Cartaya explains.

Following each expedition, the teams—made up entirely of volunteers—donate their data to the federal agencies that protect and monitor these places, passing along vital information that could help save lives or assist scientific breakthroughs.

“A glacier cave isn’t just a hole in the ice,” Cartaya says. “It’s a whole ecosystem—just an extreme one.”

The Magazine of The Sierra Club

The Magazine of The Sierra Club