Letter From Lake Tahoe

Housing sprawl in the woods and corporate-fueled climate change make for a combustible mix

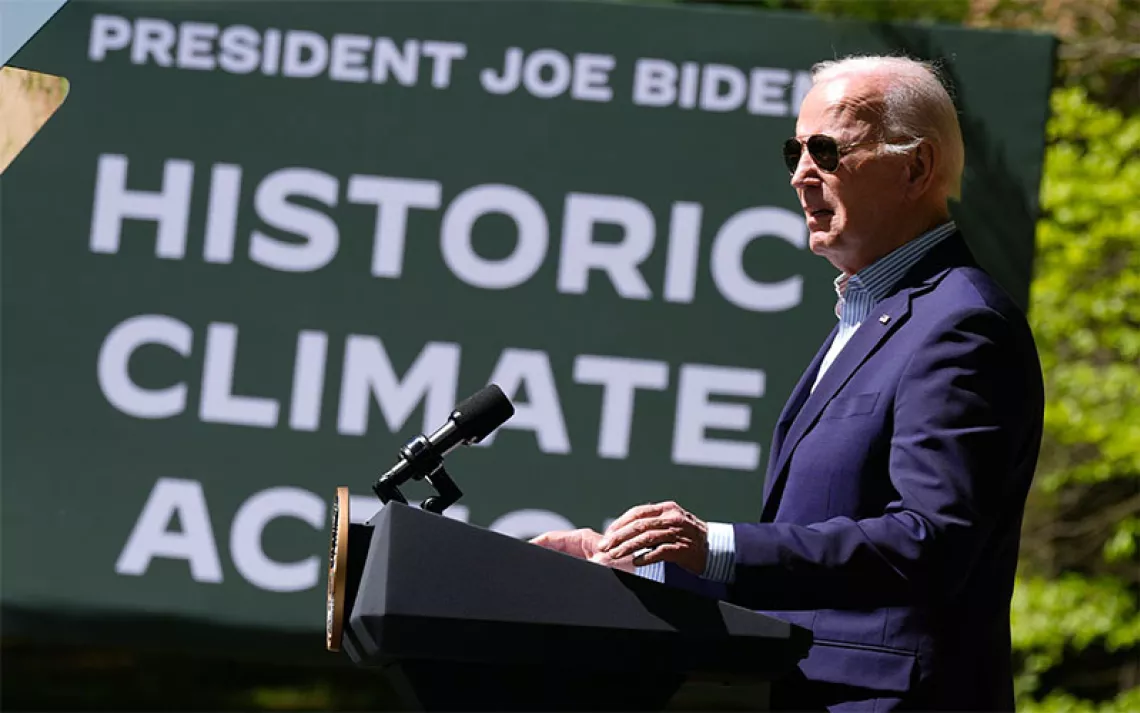

Boats float in the water away from a dock in South Lake Tahoe, California, on Tuesday, August 31, 2021, as the Caldor Fire approaches Lake Tahoe. A huge firefighting force gathered Tuesday to defend the lake from the raging wildfire that forced the evacuation of California communities on the south end of the alpine resort and put others across the state line in Nevada on evacuation notice. | AP Photo/Jae C. Hong

Here in the Lake Tahoe basin, the long-standing rule among locals is that you never plant a garden before Father's Day because there's always a freakish snowstorm in June. Not this year. Summer hadn’t even officially started when we began experiencing 90-degree weather. It wasn't the triple digits of Portland's heat dome, but it was really, really weird.

So it wasn't a huge surprise when the fires started in late June. By early July, the smoke had settled into this forested region like a Bay Area COVID transplant who refused to leave. The smoke got trapped in the lake basin (as it sometimes does) and just stayed there. Day after day my family and I suffered from burning eyes and sore throats. Everything smelled like a campfire, and even inside it was a struggle to breathe. My kids, finally free from Zoom school, were trapped inside by a combination of smoke and selfishness as a segment of the population decided for all of us that their beliefs matter more than ending a pandemic. The only silver lining: The tourists went home. By August, even some of the people that had moved here during the pandemic had decided to leave.

Last week, with the AQI approaching 500 again (that's where the chart ends: hazardous), my five-year-old told me he felt like he was choking and his chest hurt. It's the sort of situation in which you leave if you can, so we did. Then, last Friday, a friend texted that the wind had shifted, so we headed home. But by Monday the Caldor Fire was starting to look really scary. Evacuation orders came for South Lake, then West Shore, then a warning for much of the rest of the basin. The Cal Fire chief encouraged everyone to evacuate early, and all I could think of were photos I'd seen of people trapped in their cars trying to leave the basin. So we packed up and headed out again as fast as we could.

It was a different sort of packing experience the second time. Last week, I brought what we needed for a few days. This week, I took anything I wouldn't want to lose if our house burned down. Now we're posted up close by, watching for updates and keeping an eye on the wind. Right now, it looks OK for us and our town. But it’s another story entirely for our neighbors to the south, who remain at risk and cloaked in smoke.

Meanwhile, all the usual fire debates are flying around online: It's climate change! No, it's not; it's forest management! You're a climate denier! You're a climate alarmist! There’s a lot of noise but very little insight and almost no consensus.

For my part, I’m trying to keep conversations focused on the larger forces at work. Yes, it's all of the above: decades of poor forest management, too much dry fuel, and a mix of too-hot temperatures and zero humidity—particularly at night—from corporate-fueled global warming. Plus, the big problem hiding in plain sight: development decisions that have led to sprawl in the woods and left us with homes in the middle of a tinderbox.

Seven years ago, I was the Tahoe-area reporter for a couple of public radio stations, which required attending a lot of planning commission meetings. Every meeting was essentially the same conversation. Developers would present their plan for a couple dozen giant, multimillion-dollar homes and say, roughly, "Well, sure our environmental impact and egress plans look pretty bad, but you have to remember, these are second homes. We're talking 20 percent occupancy rate on average."

And then a community advocate would get up with an easel and a rendering on poster board of what Highways 267, 89, or 50 would look like if there happened to be a big wildfire on the Fourth of July weekend when occupancy was much higher. I saw that same image during at least three different meetings, but it would have been burned into my brain after one view. Because it was terrifying. It was a parking lot of cars trapped on a narrow road with fire lashing both sides—not all that different from the smoke-choked traffic jams that did in fact happen on Highway 50 just this past week.

At the same time that developers were pushing lavish second-home developments, local environmental and housing groups were talking about how the planning decisions of the 1970s had successfully limited building in some ways but had inadvertently encouraged sprawl. They were looking for ways to increase density in a few towns around the lake and return large segments of lakeshore to something resembling nature. Smart-growth advocates would comment at these meetings too, and environmentalists would present warnings about how unchecked development would threaten the famous water quality of Lake Tahoe and chew farther into the forest.

But the lion's share of public comments were from pissed-off locals. Restaurant servers and teachers and scientists, young and old, all saying the same thing: We have a housing crisis here. We don't need any more second homes. We need regular homes, ideally smaller ones, with density. It's the classic conflict when you live in a place that a lot of people like to visit, where tourism is both an economic engine and a pain in everyone's ass, where decisions to prioritize visitors are always this close to destroying the thing that draws them in the first place.

After a few of these meetings, I started to dig into the Tahoe housing crisis, to try to figure out what could feasibly be done about it. I talked to the folks who live in mobile home parks two streets off the lake, places where tourists never venture. I talked to restaurant owners in Truckee who wanted to do right by their workers but couldn't afford to pay them what it cost to live in town and still keep the doors open. I talked to a second homeowner who hated the idea of high-density housing in the area because he "didn't want it to look like Emeryville—I come here to get away from that."

In South Lake Tahoe, the place most threatened by the Caldor Fire, the contrast between visitors or second homeowners and locals was starkest, the wealth gap particularly crude. Local families were living in motel rooms while second homeowners Airbnb'd their vacation houses to tourists. A teenage girl I met outside one of the motels said she'd lived there all her life and she liked it fine. Both her parents worked at resorts in town, and she liked that she could walk to the lake. At a weekly meeting for Latina moms in the area, I heard about landlords who refused to fix things and motels that were illegally operating as apartment buildings. And I heard about why all the struggle was worth it: It's beautiful here, and safe, a place where people feel like they can give their kids a healthy start.

And then—around 2017—it seemed like our famously glorious summer season was replaced by what you’d call smoke season. That year, as I was reporting on the Wall Fire, a Cal Fire spokesman told me, “Nighttime is usually when we can get the upper hand on these fires because there’s typically higher moisture. That didn’t happen with the first few nights ... we’re hoping tonight will be different.” It hasn't really been different with any fire, any night since then.

But even as our woodland paradise took on the gray tinge of smoke, the tourists and the vacation homeowners kept coming here because, well, it’s beautiful.

If you've ever lived in a heavily touristed area, you know there are rules around who can call themselves local. I've been here almost 10 years now and had a baby in the local hospital, so I'm really getting there, but not quite. We locals look forward to shoulder season, in between the ski and summer rushes, which have grown shorter as climate change stretches out summer. When the pandemic took hold, we suddenly had shoulder season in the middle of the usual winter rush. It was an epic snow year, which ironically enough turned out bad for the resorts, since they had to close during what would have been a very successful ski season. But locals were happy having the mountains to ourselves for a moment.

As the pandemic dragged on, things changed. Second homeowners trapped in San Francisco apartments during quarantine figured, “Hell, may as well ride this out in Tahoe.” Our realtor neighbor started talking about how many people were showing up and paying cash for houses. Men wearing their masks under their noses would shout-talk about it in the post office. There were rumors that our schools would be overrun by pandemic transplant kids. And we had the sort of traffic we'd usually see on Fourth of July weekend all the time. People seemed to think they were "in nature," so pandemic guidelines didn't apply. Hospitals got crowded. It was a mess.

And all I could think about was fire season and how those Fourth of July occupancy rates were year-round now, and that if there were a fire nearby, we were all really screwed.

*

The chronic housing inequalities in the Lake Tahoe basin, the influx of COVID transplants, and the increasingly intense wildfires all lead to what should be an uncontroversial conclusion: We can't keep building into the wildland urban interface and putting more and more people in places where, when the fires inevitably start, they will be in harm’s way. And, importantly, where those houses will stop the natural fire cycle from doing its thing. The presence of homes in places where fires have always burned has led to a complete intolerance of fire, according to Jack Cohen, a research scientist with the US Forest Service. There is also now a general belief that all fires are intense enough to set our homes ablaze, a fear which has paradoxically made the wildfire season worse. How so? Instead of allowing a number of low-intensity fires to burn off a good number of trees as seedlings, we’ve all but eliminated such fires. That allows more trees to grow taller, creating a large and connected tree canopy that helps fire spread. “We’re working against ourselves," Cohen once told me.

We also probably need to separate out the budgets for forest management and firefighting. As a reporter in the West, I can't remember ever not reporting on fires, and for at least the past decade, foresters have been telling me their budgets are eaten up entirely by the fires. Way back in 2015, the Forest Service released an alarming statistic: For the first time in history, more than half the agency’s annual budget was going to fight wildfires, compared with 16 percent in 1995. “The fires are sucking our funding from just about everything else we do,” Tom Blush, with the USFS, told me at the time.

And, most important, we absolutely must stop burning fossil fuels. The forests burning up right now were once carbon sinks. Now they're gone, and the carbon embedded in the trunks have been sent back into the atmosphere. Every morning when I check the Cal Fire report, it says, "The fire remained very active overnight due to the extremely poor humidity recovery and warm temperatures." Or, shorter: Climate change is exacerbating the conditions that lead to longer, larger fires. You can blame out-of-control housing development and lousy forest management all day long for starting fires, but it's climate change that keeps them going and growing. It’s climate change that keeps them burning just as intensely through the night as they do in the day, which in turn keeps firefighters from getting any break at all.

Thousands of people have already evacuated from the Lake Tahoe basin, and it’s unclear when we’ll all be able to return safely. Several thousand second homeowners have decided to skip out on Labor Day Weekend in Tahoe this year. So far, I've seen a few folks offer Airbnb discounts on their holiday homes to evacuees, but only one ventured onto the Truckee-Tahoe Facebook page to offer his place for free to anyone evacuating. Now that's a local.

Photo by Amy Westervelt

The Magazine of The Sierra Club

The Magazine of The Sierra Club