On Its 15th Anniversary, Climate Week Is Still Rife With Corporate Greenwashing

This year’s sponsors included some of the most notorious polluters

The March to End Fossil Fuels on September 17. | Photo by Marlowe Starling

New York City’s annual Climate Week has just about wrapped up, with the usual guise of inspiring climate solutions. But there’s one glaring disconnect: It is sponsored by some of the biggest perpetrators of the climate crisis.

This year’s lineup of sponsors wasn’t particularly surprising. As in years past, some of the most notorious corporate giants were headliners of the weeklong event, including plastic polluters and greenhouse gas emitters such as PepsiCo, Nestlé, and Anheuser-Busch InBev; consulting firms and banks financing fossil fuel companies such as McKinsey & Co., KPMG, and Boston Consulting Group; pharmaceutical giants Johnson & Johnson and AstraZeneca; PFAS manufacturer Saint-Gobain; and gas-firing tech giant Siemens.

These polluters are “writing the checks and therefore having a heavy influence over what comes out of this [climate] week,” said Rachel Rose Jackson, director of climate research and policy at the nonprofit Corporate Accountability. “Corporations have a profit-driven motive that they're legally, financially, business-wise and otherwise completely beholden to, so they have one primary priority, which is to make as much money as possible.”

Some of these same sponsors were also invited to last year’s Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) COP27 climate summit. When industries and companies that are drivers of the climate crisis command a seat in the policymaking sphere, Jackson said, it creates a fundamental conflict of interest. “The last people you want putting the fire out are the arsonists holding the hose.”

A spokesperson for Climate Group, the host of Climate Week, did not provide Sierra with specific details about its process or criteria for selecting sponsors. “If we find out members or sponsors are actively delaying the transition to a net-zero future, we clarify the situation with them and if it can’t be resolved the relationship ends,” the spokesperson wrote in an email, adding that some partners “speed up their action” by “celebrating” their successes at Climate Week and then gather inspiration to do more.

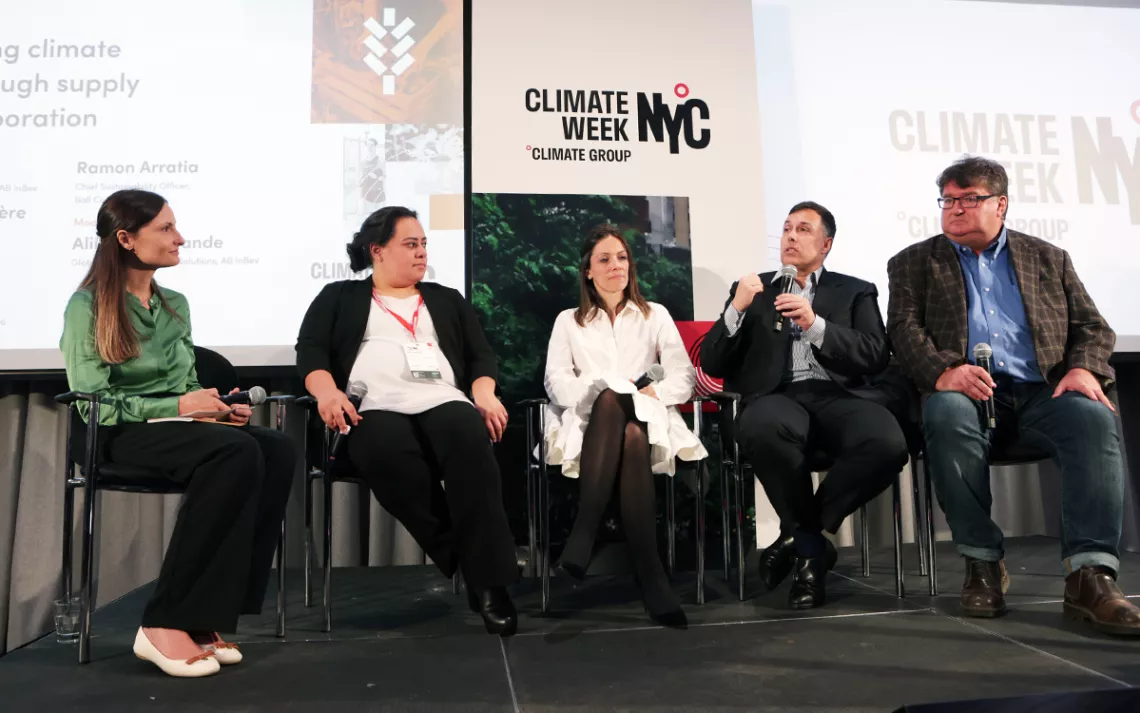

Panelists Irene Espinola Campos (Grupo Bimbo), Anna Stanley-Radière (Climate Sustainability), Ramón Arratia (Ball Corporation), and Andre Fourie (AB InBev) discussed transparency and supply-chain emissions data in a Climate Week panel on Tuesday. | Handout Photo Climate Week NYC

Top executives for these sponsors and other companies sat on a series of panel discussions Monday and Tuesday focused on decarbonization, low-carbon technology, and energy efficiency—all with a strong eye toward profit and the economy. The events provided a stage for business leaders championing net-zero emissions targets in the coming decades, commitments that often lack teeth. A new investigation launched by the Guardian shows the same is true of many carbon-offset projects.

“These transnational corporations are all part of trying to put forward a false narrative that these beautifully sounding net-zero pledges and pathways can save us from climate catastrophe,” Jackson said. “But what they're failing to tell us is that when you look at the detail of these plans, almost without exception, they actually pave the way for more emissions.” (One egregious example is Chevron.) There’s also no legal framework requiring companies to properly disclose their political activity or to hold them to their commitments, adds Nick Guroff, a consultant for Corporate Accountability.

Examples of greenwashing at Climate Week abound: A top executive at Constellation Energy Corporation referred to nuclear energy as “clean technology.” One session focused on putting steel “at the heart of the green economy”; it's an industry that, combined with iron production, accounts for about 11 percent of global carbon emissions. (Meanwhile, the CEO of Australian mining company Fortescue—one of the largest iron ore producers in the world—hailed the economic opportunities of renewable energy sources in African countries.) And Silvia Pavoni, editor of Financial Times’ Sustainable Views section, spoke at length about using blended finance and philanthropic dollars to “de-risk” investments in “developing countries” for things like solar farms and green ammonia—products for export to wealthier nations.

Yet last year, only 12 percent of philanthropic capital was actually implemented, said Harish Hande, CEO of the SELCO Foundation, an Indian renewable energy nonprofit. “You can have all the policies in the world; you can have (the) best of the papers written,” he said during a panel discussion. “The question is, who’s going to do it? You see the number of practitioners in this conference? Less than 2 percent.” Hande pointed to the lack of investment in solar energy for health facilities, especially in parts of the world where newborn delivery rooms that “look like execution chambers” need more energy-efficient sterilizers.

Other corporate executives avoided mention of their companies’ ties to oil and gas by focusing instead on euphemistic net-zero goals. Cisco’s chief sustainability officer, Mary de Wysocki, spoke in general terms about the importance of partnering with companies providing renewable energy around the world and how digital technology could help companies reduce their emissions. She failed to acknowledge that Cisco provides cybersecurity and communication services to oil and gas companies.

Many of Climate Week’s biggest sponsors still service oil and gas too, such as Google. Chief Sustainability Officer Kate Brandt detailed Google’s use of AI to make predictions and administer early warnings about major floods. She also praised the company’s progress toward its sustainable development goals. But Google has also paved the way for oil companies to greenwash by targeting oil’s search engine optimization (SEO) to “eco-friendly” search terms.

McKinsey & Co., a global management consulting company and a major sponsor, was recently named in a lawsuit filed by Multnomah County in Oregon for working with at least 17 oil and mining companies—including Chevron, Saudi Aramco, ExxonMobil, Royal Dutch Shell, BP, and a slew of others. Multnomah County argues that McKinsey “participated in a deliberate misinformation campaign” to deny and downplay the causal relationship between its clients’ actions and their decades’ worth of greenhouse gas emissions.

Saint-Gobain, another headlining sponsor, has polluted environments and communities near its manufacturing facilities with PFAS, the toxic “forever chemicals” that accumulate in water, soil, air, humans, and other animals. High concentrations of the chemicals have been linked to several forms of cancer, especially in communities neighboring its manufacturing facilities. In New Hampshire, the company only recently announced its plans to permanently close by 2024.

And at Thursday’s New York Times Climate Forward event, PepsiCo’s chief sustainability officer, Jim Andrew, boasted commitments like reducing small percentages of virgin plastic, replacing plastic rings around cans (the ones that choke marine life) with cardboard, and participating in UN treaty negotiations that “make sure everybody plays their part.” PepsiCo is the second-largest plastic polluter behind Coca-Cola. The company is a member of the Alliance to End Plastic Waste, a group composed of fossil fuel and petrochemical companies, but many of them lobby to continue producing plastics and toxic chemicals. (Nestlé and Unilever, two other Climate Week sponsors, rank in third and fourth on the global plastic pollution scale.)

Some executives spoke more transparently about their carbon footprints. Anheuser-Busch InBev, an international brewing company and major sponsor of Climate Week, sourced just 7 percent of its energy from renewables when it committed, in 2017, to transitioning to 100 percent renewable energy by 2025—now less than two years away. As of 2021, that number reached 39.9 percent, according to its 2022 sustainability report. But other executives appeared less genuine in their transparency efforts.

“Transparency is a trend, whether you like it or not,” said Ramόn Arratia, chief sustainability officer for Ball Corporation, best known for its aluminum and glass manufacturing. “There will be winners and losers, and we think that the more information you have, the better the competitive advantage.” Andre Fourie, AB InBev vice president of sustainability, added that suppliers are hesitant to share their emissions data. “There are ways of making the data transparent without exposing yourself,” Fourie said during the panel.

Irene Espinola Campos, director of net-zero initiatives at Mexican food company Grupo Bimbo, spoke more candidly about companies openly reporting their carbon footprints. “It's just another number for the company that should be public,” she said during a panel. “But the truth is—and perhaps I'm going to be the negative person in the group—it's not happening.”

During a panel designed to appear neutral on “clean tech,” titled “Silver bullet or red herring,” Hande, the Indian solar nonprofit CEO, piped up: “We need to stop talking,” he said. Renewable energy is “no longer a silver bullet and red herring. It's the oxygen. It is the only way to survive.”

The room fell silent.

The Magazine of The Sierra Club

The Magazine of The Sierra Club