The IPCC Says There’s Still Time. So Now What?

The report is full of warnings—and a whole lot of hope for the future

Wetlands near Palm Beach County. | Photo by Lisa5201/iStock

It was not long ago that the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change was accused (rightly) of being cautious to the point of mendacity. The IPCC has historically been timid about making statements that reached scientific consensus in other circles decades ago. As journalist Emily Atkin put it, “scientists have known carbon dioxide traps heat for longer than women have had the right to vote. The warming nature of greenhouse gases was discovered by a literal suffragette in 1856.”

A lot of the science that the IPCC has hedged over felt to outsiders like a debate over whether the earth is round or just really, really seems that way. In 2021, the IPCC somehow released an entire 42-page summary of the “current state of the climate, including how it is changing,” without once mentioning a certain class of hydrocarbons known as fossil fuels. Instead, its authors referred vaguely to human “activities” and “influence.”

It is no longer the olden days of two years ago. Earlier this week, the IPCC dropped its Synthesis Report of the IPCC Sixth Assessment Report and threw this statement into the mix, with its usual thick frosting of confidence intervals:

In 2019, atmospheric CO2 concentrations (410 parts per million) were higher than at any time in at least 2 million years (high confidence), and concentrations of methane (1866 parts per billion) and nitrous oxide (332 parts per billion) were higher than at any time in at least 24 years (very high confidence).

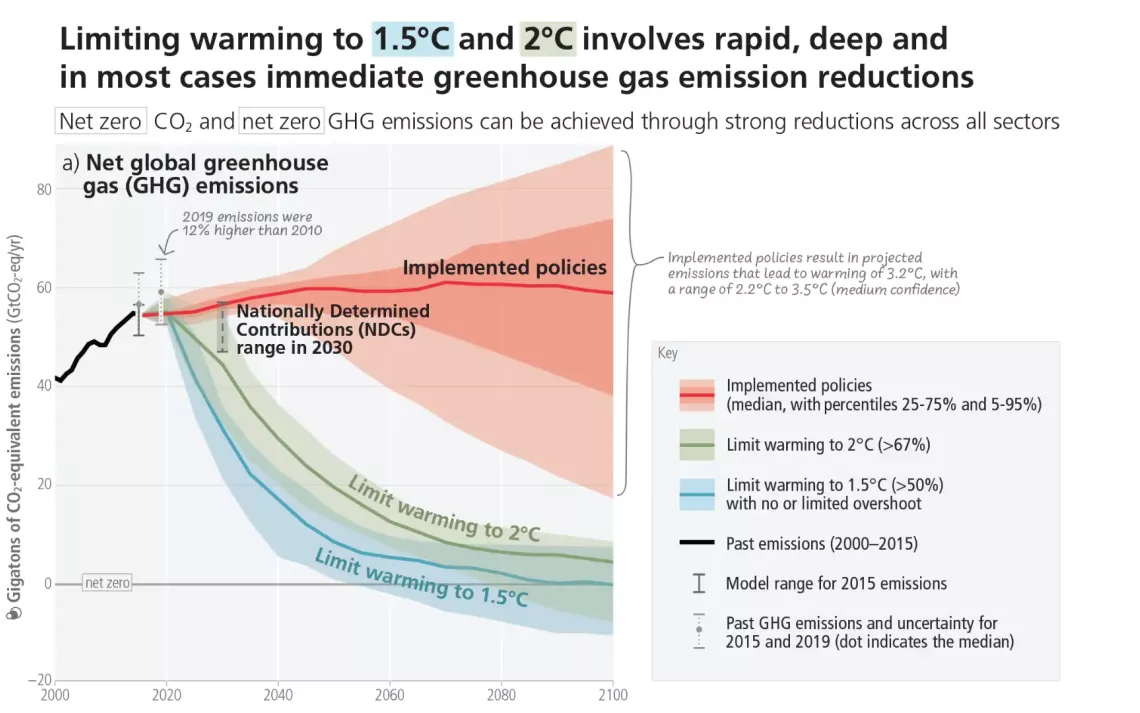

Global greenhouse gas emissions are 12 percent higher than they were in 2010 and 54 percent higher than they were in 1990, the IPCC continued, with the majority of these emissions coming “from fossil fuels combustion and industrial processes.”

This accurate placing of blame where blame is due is a big deal. “Climate change is a threat to human well-being and planetary health,” the summary continues—admittedly not saying anything that climatologist James Hansen didn’t already tell Congress in 1988, but still, better late than never. “There is a rapidly closing window of opportunity to secure a livable and sustainable future for all.”

A helpful image showing just how much current climate agreements aren't cutting it. Courtesy of IPCC.

This new summary covers a lot of familiar terrain, including reports that the IPCC has published in the past about the likelihood that global warming will exceed 1.5°C (2.7°F) during the 21st century (very likely).

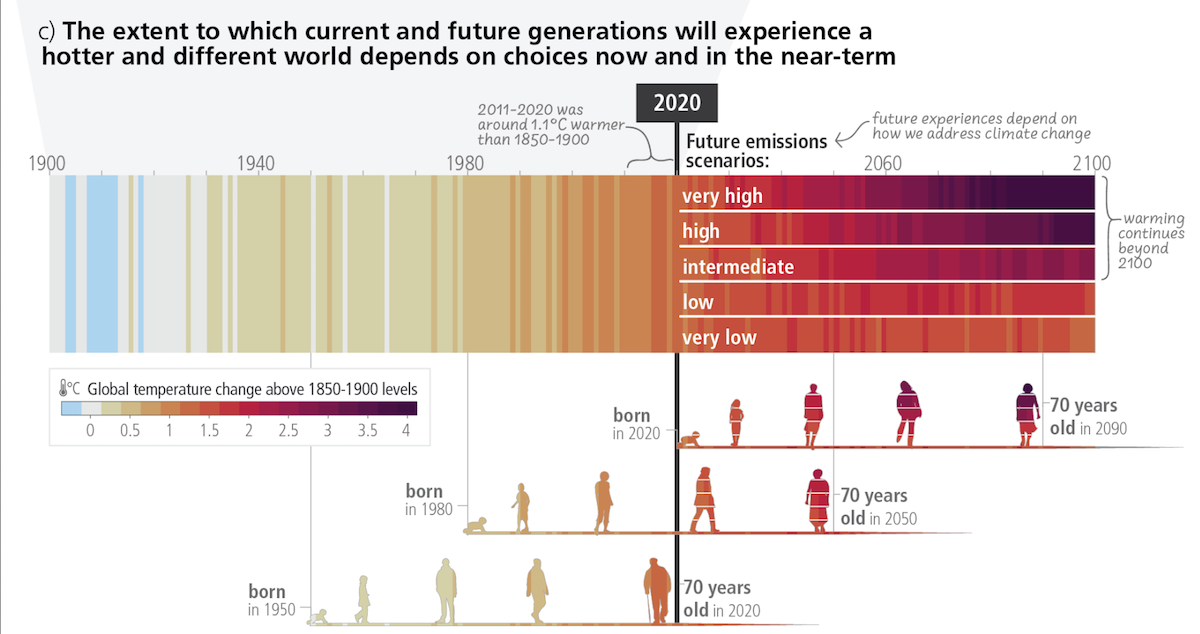

But, the body emphasizes, if greenhouse gas emissions drop quickly enough, that warming will only be temporary, and climate disruption could begin to reverse before the end of the century, although some legacies of our greenhouse gas emissions will last a very long time. “Sea level rise is unavoidable for centuries to millennia due to continuing deep-ocean warming and ice sheet melt,” writes the IPCC. “Sea levels will remain elevated for thousands of years.” But changes to temperatures (especially on land) and on ocean acidification (at least in the shallower parts of the ocean) can reverse much more quickly. The children born during the remainder of this century could grow up in a world where the climate around them becomes safer and less volatile as time goes on.

The IPCC has recommendations for how we can bring about that world. Here are a few of them.

Stop financing fossil fuel infrastructure for real

Financing for lower-emissions technology has increased in the last decade, the IPCC reports, but “growth has slowed since 2018.” But that financing still doesn’t come close to what is spent on technology that is actively trashing the middle atmosphere. Public and private finance flowing into fossil fuels development, writes the IPCC, is “still greater than those for climate adaptation and mitigation (high confidence).” It's likely that this language would have been even stronger but UN members like Saudi Arabia successfully negotiated to weaken language on phasing out fossil fuels, and added references to carbon capture instead.

The IPCC also reports a substantial “emissions gap” between projected global greenhouse gas emissions in 2030 if member nations stick to the COP26 agreement and what countries actually need to do to limit warming to 1.5°C. “Without a strengthening of policies, global warming of 2.2–3.5°C is projected by 2100 (medium confidence).”

Take care of the green stuff

In terms of conservation, writes the IPCC, “maintaining the resilience of biodiversity and ecosystem services at a global scale depends on effective and equitable conservation of approximately 30% to 50% of Earth’s land, freshwater and ocean areas, including currently near-natural ecosystems.” This might seem indulgent, but the alternative is a future of continual flood, landslide, and drought. “Ecosystem-based adaptation approaches such as urban greening, restoration of wetlands and upstream forest ecosystems have been effective in reducing flood risks and urban heat.” This is despite the fact that climate adaptation is underfunded compared to spending money to repair damage that has already happened—and especially underfunded compared to spending money to put in more fossil fuel infrastructure that will ultimately cause further damage.

Adaptation won’t work in every landscape. The IPCC warns that some tropical, coastal, polar, and mountain ecosystems may be in too much flux already to try to arrest or slow down whatever changes they are going through. Nevertheless, “disaster management, early warning systems, climate services, and social safety nets have broad applicability across multiple sectors.”

Don’t trust anyone cavalier about overshooting 1.5°C

Only a small number of modeled pathways to limit global warming to 1.5°C by 2100 do so without temporarily going past 1.5°C of warming along the way. The problem with overshooting is that it increases the risk of feedback loops. Wildfires, massive tree die-offs, drying peatlands, permafrost thawing, and other dire catastrophes could put a difficult-to-predict level of greenhouse gas into the atmosphere just as emissions are supposed to be declining. Plus there’s the extinction factor. In an earlier report the IPCC pointed out that 70 to 90 percent of existing tropical coral reefs will disappear even if global warming is kept to 1.5°C.

Just look at all that burgundy. | Image courtesy of IPCC

“Compared to pathways without overshoot, societies would face higher risks to infrastructure, low-lying coastal settlements, and associated livelihoods,” the summary continues. “Overshooting 1.5°C will result in irreversible adverse impacts on certain ecosystems with low resilience, such as polar, mountain, and coastal ecosystems, impacted by ice-sheet, glacier melt, or by accelerating and higher committed sea level rise.” Some carbon-removal boosters hope that the technology will be advanced enough that it can mechanically prevent overshoot by 2100, even if emissions don’t drop enough, but that’s a big gamble with the biodiversity of life on Earth. Possibly the biggest gamble ever?

Cities don’t look like nature, but they’re still important

At their best, cities cluster people in areas where they can share infrastructure and green space, and leave the actual wilderness to the wild things. Or, as the IPCC puts it, “urban systems are critical for achieving deep emissions reductions and advancing climate resilient development (high confidence).” The summary recommends using city planning to encourage cities to be densely populated, comfortable for walking and biking, energy efficient, affordable for a wide range of residents (so that low-income people aren’t pushed out into car-dependent areas), and a place where buildings are rehabilitated rather than torn down and rebuilt.

Remember that every single increment of reduced emissions counts

Or, as climate scientist Adam Levy puts it, “It’s never too late to stop punching yourself in the face.”

The IPCC puts this scientific reality in milder terms. In the short term, scientists are already seeing an increase in heat-related health problems; food-borne, water-borne, and vector-borne diseases; mental health challenges; flooding in coastal and other low-lying cities and regions; biodiversity loss in land, freshwater, and ocean ecosystems; and a decrease in food production in some places.

But, the IPCC continues, “With every additional increment of global warming, changes in extremes continue to become larger. Continued global warming is projected to further intensify the global water cycle, including its variability, global monsoon precipitation, and very wet and very dry weather, and climate events and seasons.” Other things that can always be worse according to the IPCC include sea level rise, ocean acidification, deoxygenation, heat waves and droughts, intensification of tropical cyclones, and “fire weather.”

No wallowing in despair, plz

These IPCC reports can get bleak, but this summary gets downright chipper at times. In many ways, its recommendations are reminiscent of the solutions put forward by the similarly UN-backed Intergovernmental Science-Policy Platform on Biodiversity and Ecosystem Services. Like the IPBES, the IPCC recommends supporting Indigenous sovereignty as an important part of ecosystem protection and sees ecosystem protection and restoration of fishing, hunting, and foraging areas as an anti-poverty measure as well as climate policy.

The summary is gleeful about the implications that cutting greenhouse gas emissions have for public health and quality of life worldwide “Feasible, effective, and low-cost options for mitigation and adaptation are already available (high confidence)” reads one section. “Many mitigation actions would have benefits for health through lower air pollution, active mobility (e.g., walking, cycling), and shifts to sustainable healthy diets,” reads another. “Strong, rapid, and sustained reductions in methane emissions can limit near-term warming and improve air quality by reducing global surface ozone. Adaptation can generate multiple additional benefits such as improving agricultural productivity, innovation, health, and well-being, food security, livelihood, and biodiversity conservation (very high confidence).”

In other words 1000+ scientists and experts spent months sifting through dire science under the aegis of the UN. They still found the capacity to set aside the future they’re dreading and get giddy at the thought of the future that could be. Next step: actually following through.

The Magazine of The Sierra Club

The Magazine of The Sierra Club