ENVIRONMENT EXPLAINED

How Tech Has Changed Hiking

Are apps, trackers, and trail vlogs democratizing or ruining long-distance hiking?

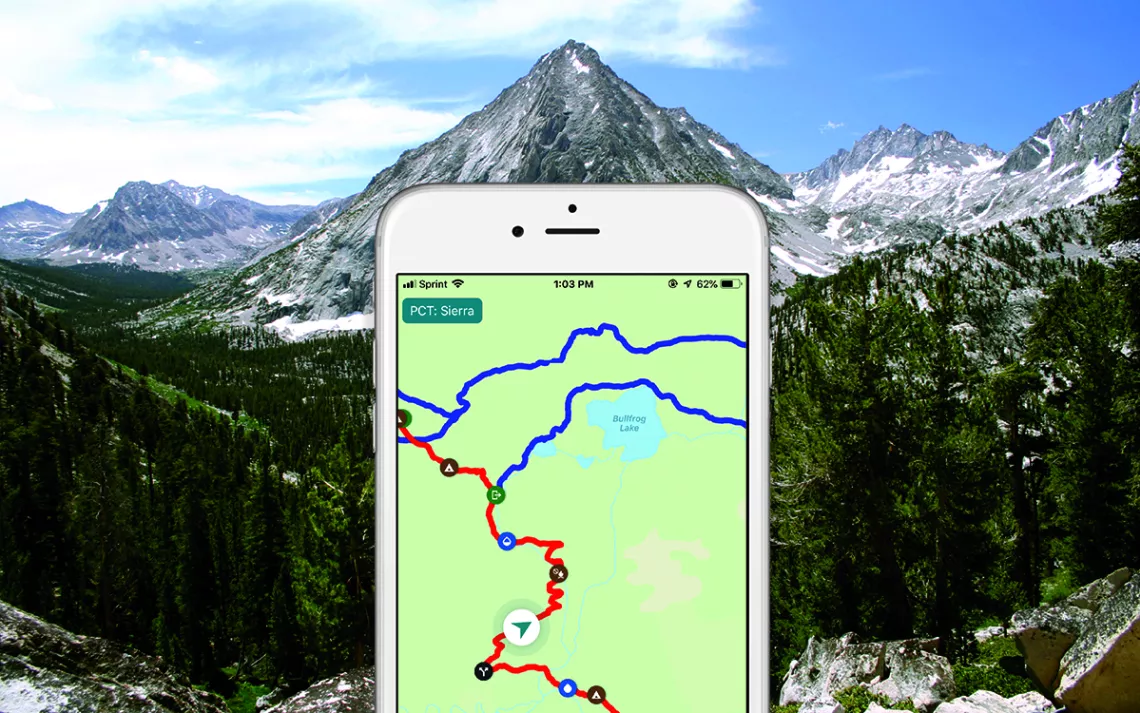

Courtesy of Guthook

Before Jean Taggart left home to conquer the 800-mile Arizona Trail last year, she made a detailed spreadsheet to organize her resupply provisions. To update friends and family on her progress, she bought a Garmin inReach Mini, which is a GPS and satellite messenger. She poured over hiker blogs and absorbed detailed information about each section of the trail on the Arizona Trail Association’s website—which also connected her with “trail angels” who could help her cache water on exceptionally dry sections of the route.

Taggart watched hikers’ YouTube vlogs that detailed nearly every step of the experience, helping her to visualize the unfamiliar trail. And she bought the Guthook Guides’ Arizona Trail app, which loaded her smartphone with detailed trail information, accessible even when she didn’t have cell coverage. She downloaded numerous podcasts and e-books to keep herself entertained during lonely stretches of trail. And she bought a high-powered Anker battery pack to keep her phone juiced up for the days-long stretches between trail towns.

If Taggart—an accomplished Seattle-based hiker who completed the Arizona Trail in November 2018—had undertaken the trail 10 or even five years ago, her experience would have been quite different. When she and her now-husband, Jared Kofron, logged 1,100 miles of northbound hiking on the Pacific Crest Trail in 2014, for example, they used a few trail apps in combination with paper maps. Atlas company Guthook, which came out with its first trail app (for the PCT) in 2012, was still relatively new then. Trail vlogs were less common, and Garmin hadn’t yet released the inReach Mini, a much smaller and lighter version of its previous GPS-enabled trackers. Rewind even further and hikers taking to any number of long-distance trails hiked without any digital assistance whatsoever.

There’s no doubt that technology has changed the way we hike, as it has all aspects of modern living. In the hiking world, tech perhaps has the most dramatic influence when it comes to long-distance undertakings—those that require weeks or months to complete. Tech has allowed hikers to upgrade to extremely lightweight gear, dramatically reducing pack weight. It’s enabled hikers to enter the wilderness armed with better route-navigation tools than ever before. And it’s potentially empowered people less experienced than Taggart to strike out on new adventures, armed with more information than ever before.

“Technology wasn’t why I decided to get into long-distance hiking,” Taggart says. “But for so many others, technology helps it become a possibility. It opens a door because there’s so much information out there.”

Is tech dumbing down what was once an undertaking best left to the skilled, or is it also democratizing these adventures, making them possible for people who might otherwise not have access? Is it blurring the lines between wilderness and civilization and detracting from the experience—or adding to it? It’s a philosophical question as well as a practical one.

Researchers have looked into whether technology like personal locator beacons—which can send rescue requests to the nearest search-and-rescue team with the push of a button—and smartphones, satellite phones, and GPS units affect one’s decision-making in the wilderness. Do such devices give users a false sense of security, thus leading them into dangerous situations?

The results have been mixed. But for the most part, hikers—especially solo travelers like Taggart—say they feel safer and more prepared, and thus enjoy their experiences more. They say they’re more likely to travel alone in the wilderness, that they don’t feel they take additional risks just because they carry tools like a PLB. While these studies didn’t look at long-distance trails specifically, the results are likely applicable.

It's a topic familiar to Jack Haskel, trail information manager at the Pacific Crest Trail Association, the nonprofit tasked with protecting and promoting the 2,650-mile trail stretching from the southern edge of California to the northern border of Washington State. Haskel says the PCT has long influenced and been influenced by hiking tech. In fact, many major gear innovations—from some of the earliest ultralight backpacking equipment to apps like Guthook—have been developed by PCT alumni.

“The long-distance trail community, especially the one centered around the PCT, has a long history of birthing companies and changing backpacking,” Haskel says. “The PCT has had a big impact on hiking innovations, and a lot of that impact is technology.”

Haskel says technology—specifically internet technology—has allowed scores of people to discover what was once a little-known trail supported by a small community of enthusiasts. “The internet’s ability to let people discover new things is profound,” he says. “The PCT has thousands of websites built about it and probably millions of other posts about it, helping people dive deep into the relatively obscure world of a 2,600-mile-long wilderness path.”

The internet has helped hikers build expertise in preparation for the trail, he says, and has kept people passionate about and connected to it long after they’ve stopped hiking, reduced barriers for the less experienced, and helped bring in users from a more diverse set of backgrounds, nationalities, and identities. “Technology is at the root of how the PCT has become well-loved and known around the world,” Haskel says.

Nowadays, adventurers who may not undertake a thru-hike because of physical limitations have newfound access: Mike Hanson, a blind man who conquered the Appalachian Trail in 2010 with the use of a Loadstone GPS device, is one prominent example. Today’s AT thru-hikers have cellphone service almost daily, enabling them to post updates online, contact friends and family, and potentially get out of trouble—assuming, of course, that their batteries stay charged and nothing breaks.

Haskel notes, however, that access to information is no substitute for firsthand experience. “We have people who have done seemingly all of their research and prep through YouTube videos. Watching a video is not the same as building a personal experience,” he says. And of course, it’s important to strike a balance between increased use and overuse—the more trails are promoted online through avenues like vlogs and Instagram, the more they’re susceptible to becoming overrun. At the same time, the PCTA is better able to spread the word about Leave No Trace principles and safety practices—reaching a wider range of people via free tools like Instagram—and to raise money for the trail’s protection.

Overall, Haskel says, this increase in technology is a good thing. After all, when trails—long-distance and otherwise—are discovered and used by a wider audience, they’re then beloved by that wider audience. “The PCT should be famous,” he says. “It’s important that trails are used—otherwise they’re not supported. Trails disappear if they’re not used.”

The Magazine of The Sierra Club

The Magazine of The Sierra Club