This Houston Museum Teaches About Climate Change

Cofounders Aaron Ambroso and Tiffany Jin are rethinking the role that cultural institutions play in environmental justice

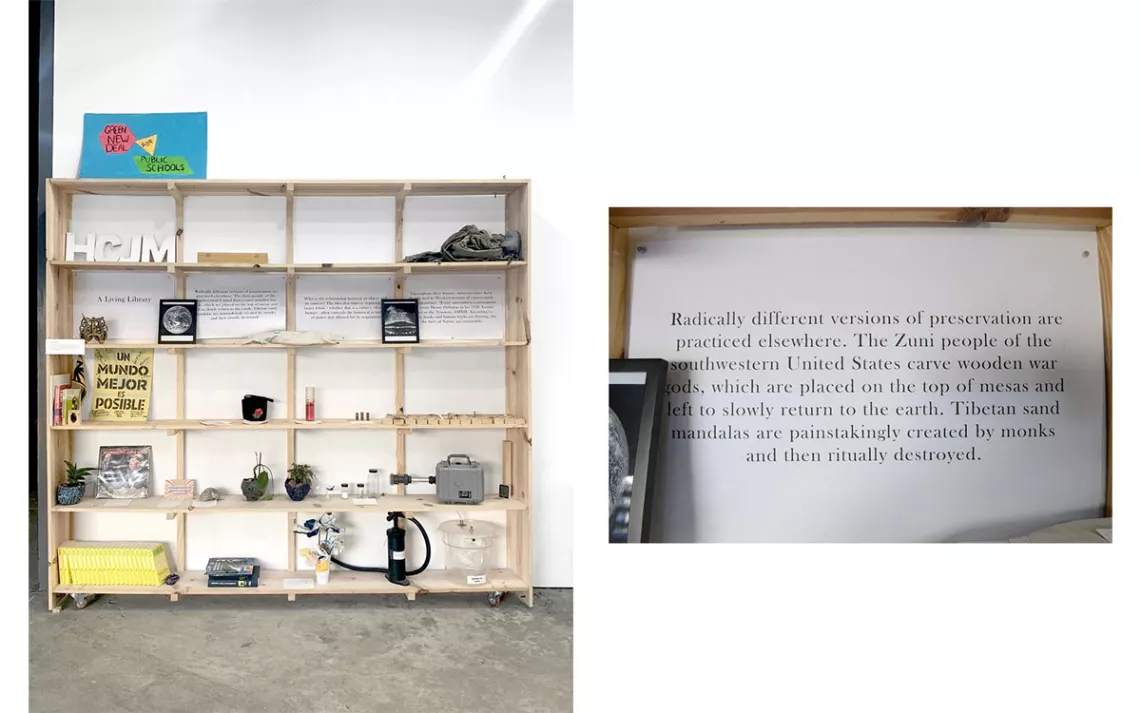

Exhibits on display at the Houston Climate Justice Museum and Cultural Center. | Photos courtesy Houston Climate Justice Museum

A pipe that burst during the February 2021 winter storm. A “Green Jobs for All” banner from the Houston chapter of the Democratic Socialists of America. A black velvet purse that survived Hurricanes Katrina and Harvey. A comic book about microplastics. A piece of asbestos.

Blurring the lines between art and world, these are just some of the items that go in and out of the Houston Climate Justice Museum and Cultural Center’s Living Library, an open-call project that invites community members to submit objects related to climate change and justice. Like books in a library, the items can be “checked out” and live a life outside of the museum. This is one of the space’s many projects and exhibitions; organizers are determined to reveal the longtime connections between art, local history, and the environment and display the intersectional complexities of climate change.

Aaron Ambroso, the cofounder of the museum, moved to Houston from his native North Carolina in 2019 with a background in museum education and art history. He later met Tiffany Jin, who grew up in the city, studied biochemistry and architecture, and has a background in art and design. The two frequently toyed with ideas of creating spaces that engaged with infrastructure like solar installation and water retention issues.

“Museums are our political spaces. Museums are doing politics—they just don't always say that they are,” Ambroso explained. “And one day, [Jin] was like, 'What are we waiting for? Let’s start one.'”

So the duo began to look for a place to build the space they wished existed. In 2021, what started as an idea in a Montrose coffee shop bloomed into the Houston Climate Justice Museum, one of just two cultural institutions in the nation centering on climate change. Ambroso and Jin eventually settled on a warehouse tucked away in the city’s Second Ward, or East End. Once used to make fittings for pipelines, the space was a leftover of sorts in the rapidly gentrifying neighborhood. The warehouse’s back end is built out into other art spaces and small businesses. Its entrance is a garage door, and the space isn’t climate controlled. The pair saw this as a perk to keep costs cheap as they rented it out while working their full-time jobs, but now, it’s become part of the museum’s identity.

“Museums are dedicated to a really strict version of preservation, but what does that mean in a world where we actually save money by not running air conditioning?” Ambroso said. “We lessen our carbon footprint by not running it.”

Exhibits on display at the Houston Climate Justice Museum and Cultural Center. | Photos courtesy Houston Climate Justice Museum

Many museums perpetuate what majority cultures, usually white and affluent, felt were worth preserving. “A lot of museums want to give you a sort of transcendent experience set aside from the bustle and the busyness of everyday life,” Ambroso said. “One of the challenges for dealing with climate change is getting out of that space. How do you make a museum that's part of the real world—one where going to the museum is not about escape but about getting into those processes that are every day? It’s our responsibility to figure that out.” Ambroso and Jin wanted to rethink the ways that cultural institutions, like museums, show up in conversations about race, gender, and environmental justice. “We wanted to make the museum take the curtain off, in a way, and have more discussions about whose culture was being presented in museum stories,” Ambroso said.

The museum’s past and current exhibitions may seem completely different at first glance, but they all share a throughline of storytelling, history, and above all, the imperviousness of climate change. For example, Saúl Hernández-Vargas’s y cómo era el desierto? como una inmensa mancha de color marrón y una máquina enmohecida y un punto en una línea (translation: "and what was the desert like? it was like a large brownish mess and a rusty machine and a dot in a line") highlights life in the desert and borderlands—the life that persists amid climate-change-fueled drought and North American Free Trade Agreement policies that exacerbate displacement and migration issues; Creosote Stories interrogates the legacy and future of the creosote plume in northeast Houston through the violent systems, such as slavery and Black labor, that fueled the wood-preserving industry, which has poisoned residents; and Climate Migrations centers climate-change-fueled migration and the links between climate change and displacement.

Creosote Stories was particularly impactful as it was an oral history project in which Fifth Ward and Kashmere Gardens residents, those who knew the issue best, those who lived it—and are living it—were finally able to tell their own stories. In the vignette-like clips, they touch on the pain and perils of gentrification, the impact that cancer (which creosote has been linked to) had on their families, air pollution, their childhoods, and hopes for the ward.

Sandra Edwards, a longtime resident of Fifth Ward and participant in the Creosote Stories exhibition, moved back to Fifth Ward to take care of her grandfather who died from bone cancer and holds the devastating timeline of creosote contamination close. “Everybody knew everybody; we all helped each other out,” Edwards recounted. “Then next thing you know, cancer is hitting house after house after house. People try to move away, but they still wind up getting cancer.” Edwards has been a community activist for decades now and said she was “honored” to be a part of the exhibition. “This was for my community,” she said. “People need to know what we are going through and how much help we are not getting. And we deserve acknowledgment.”

Willow Naomi Curry, a guest curator for the exhibition and Kashmere Gardens native, stressed that museums are inherently colonialist structures, so the need to tell stories as they’re happening felt all the more urgent. “Activists and advocates are historically exploited and sacrificed groups in the US,” Naomi Curry said. “There's usually not an attempt to center or even include them in our storytelling or our cultural institutions, so we have to. Because when these stories do finally end up in say, schoolbooks, you don’t usually get to see the frontline activists who brought these changes.”

She continued: “We can’t just wait a year later, five years later, 10 years later, when the harm has ballooned into something much larger. We can’t forget people—these activists, these residents, and their experiences.”

In a space like the Houston Climate Justice Museum, where most artifacts are in various states of decay, Ambroso and Jin saw this decision as a method of preservation or documenting the city’s climate history. “Museums are relatively Western ways of preserving the world, while many other people find meaning in the destruction or slow degradation of cultural artifacts,” Ambroso said. The Living Library, an ongoing collection that started in 2021, directly confronts the Western concept of preservation, questioning who gets to choose—and contextualize, for that matter—the items that are put in museum spaces. “One of the challenges of climate change is that you can't really collect it, since it’s about broad patterns over time,” Ambroso said of the impermanent collection. “So we wanted to just invite people to drop off things that were relevant to environmental justice issues in Houston. It was a way to try to get out of the museum voice and let other people have writing within the space.”

Nature is political, especially in Houston, a city plagued by supersized highways, the remnants of slavery, gentrification, little to no flooding infrastructure, rampant air pollution, and hurricanes. And the Houston Climate Justice Museum wants to reveal how all these issues are interconnected. “In this city, your zip code still determines your life expectancy,” Ambroso said. “And that has a lot to do with not just fossil fuels, but railroads, dredging, the histories of plantations, the petrochemical industry, redlining—they’re all part of environmental justice.”

In Houston, climate change is undeniable. In fact, Second Ward—the historically Latino but rapidly gentrifying neighborhood that houses the museum—is particularly vulnerable, subject to flooding and pollution caused by the mix of contamination and floodwaters. Due to the city’s lack of zoning laws, the ward is congested with industrial facilities perched near neighborhoods, infecting the residents with disproportionate rates for asthma and other respiratory issues. Neighborhoods are rapidly gentrifying around the city, which is why the Houston Climate Justice Museum works to partner with community activists, residents, and local artists and nonprofits and be a space—an archive—for everyone.

And the museum’s work is far from done.

“Every cultural institution has to ask what they’re willing to do, what they’re willing to sacrifice for the public good,” Naomi Curry said. “Museums are facing the biggest reckoning right now, and a lot of them are scared to lose what has made them possible. But we’re not. All we can do is share with each other as much as we know and unite.”

The Magazine of The Sierra Club

The Magazine of The Sierra Club