Have a Happy Winter Hut Trip

With proper advance planning, the backcountry wonderland is your oyster

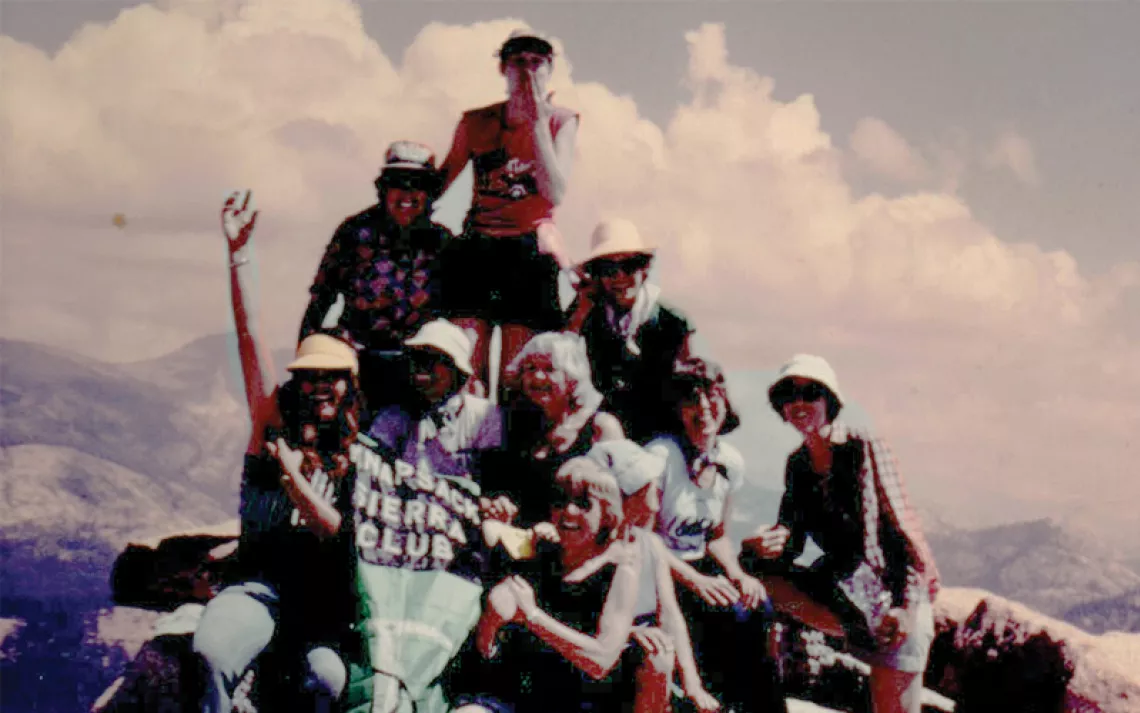

Photos courtey of Cindy Hirschfeld

The first time I set out on a winter hut trip, I traveled into the wilderness on long, svelte telemark skis and low leather boots, a group of backcountry enthusiasts showing me the way. I was excited but didn’t quite know what to expect. Now, almost 25 years later, I’ve long since upgraded my gear to sturdier-yet-lightweight alpine touring skis, and I know exactly what to expect—but still, the excitement remains. I’ve explored backcountry huts and yurts throughout my home state of Colorado, as well as in Idaho, Canada, France, and Switzerland, and these trips have become my favorite winter outings.

Why embark on a hut trip? For one, there’s the allure of skiing untracked powder in the backcountry. There’s also the unexpected pairing of solitude—being deep in the mountains—with the camaraderie that develops among you and your hutmates (whether a group of friends or fellow adventurers you’ve just met) as you set up high-altitude housekeeping, share meals, play games, and get into deep fireside conversations. And of course, getting back to basics in the wilderness—where matters such as what route to ski, how much wood to feed the fire, and the best spot on the deck for stargazing take precedence—is always a luxurious respite from the high-tech, high-stress everyday.

A trip usually begins with a trek through quiet, snow-covered forest. It doesn’t take long to fall into a rhythm, skis shuffling forward, breaths adjusting as a trail climbs, levels out, then climbs again. The ski-in can take several hours, broken up by trailside snack breaks and periodic check-ins to ensure everyone in the group is doing OK. My favorite signal that a hut is close by? Getting a whiff of wood smoke, the surefire sign that other visitors have been stoking the stove.

A trip usually begins with a trek through quiet, snow-covered forest. It doesn’t take long to fall into a rhythm, skis shuffling forward, breaths adjusting as a trail climbs, levels out, then climbs again. The ski-in can take several hours, broken up by trailside snack breaks and periodic check-ins to ensure everyone in the group is doing OK. My favorite signal that a hut is close by? Getting a whiff of wood smoke, the surefire sign that other visitors have been stoking the stove.

The Colorado huts that I frequent most often are far from the drafty, rustic structures you might envision; in fact, many inspire fantasies of log-cabin living, with two levels, multiple rooms, large windows framing spectacular views, and sizable decks. These huts are usually sited close to treeline, so they’re protected while offering proximity to wide-open vistas and soaring peaks. I’ve also stayed in many yurts—those round, one-room shelters prevalent in Mongolia. Though not as spacious as huts, and lacking the same level of privacy, yurts also make for cozy backcountry digs.

Been thinking about planning a hut trip of your own? Here are the pro trips I’ve gleaned—or learned by trial and error—through my years of mostly DIY adventuring.

How Fit, and What Type of Skier, Do I Need to Be?

Ideally, your first hut trip will be a manageable challenge. For an inaugural experience, look for a hut that’s a relatively short distance from the trailhead (up to four miles is a realistic goal) with an elevation gain low enough that the route is more of a gradual climb than a winter Stairmaster. The adventure may push you a bit outside your comfort zone, but you shouldn’t feel like a) you might just pass out on the side of the trail; b) you’ll never make it to the hut; or c) it’s the most miserable experience of your life. You’ll want to have a good fitness baseline, meaning you regularly do some type of aerobic exercise. Remember that you’ll be exerting yourself at a higher altitude than you’re likely used to.

Be at least an intermediate-level skier. The most challenging part of many hut trips is skiing back out at the journey’s end. If it hasn’t snowed in a few days, the trail may become a fast, luge-like run, which you’ll be navigating with a backpack on. If in doubt, snowshoe.

How and When Do I Book a Hut?

As backcountry skiing, and hut tripping, has soared in popularity, booking far in advance—often the preceding winter—is the new normal. That said, plans change and hut spots often open up last minute. Other than word of mouth, online forums like the one on the 10th Mountain Division Hut Association website help skiers buy and sell spots. In Colorado, some of the best huts for first-timers—Shrine Mountain Inn, Francie’s Cabin, Sangree M. Froelicher—are booked through 10th Mountain. The new energy-efficient and enviably cush Sisters Cabin, which debuts this month, is the latest offering in the Summit Huts system, and at 3.7 miles in, is also a good bet for newbies. Better yet, it’s still entirely possible to book a spot this winter, as reservations (via 10th Mountain) open January 7. This hut system is the state’s most popular, and reservations fill up quickly. On average, these huts sleep 16, and you can book either the whole hut or however many spots you need. Members of the hut association (memberships start at $35) get first dibs through an annual mid-February reservations lottery.

The hut association also handles bookings for the Braun Huts, south of Aspen. Markley and Lindley are both good options; the others require more complicated route finding and travel through potentially risky avalanche terrain. These huts are smaller, with an average of eight spots, and you must book the whole hut (whether or not you use all the spots). Reservations open up the first business day of May, by phone or online.

Other good options for first-timers include the yurts and huts in Colorado’s Never Summer Nordic system, northwest of Fort Collins, the Southwest Nordic Center Yurts in southern Colorado and northern New Mexico, the Fishhook Hut or Boulder Yurts through Idaho’s Sun Valley Trekking, and Bear River Outdoor Recreation Alliance yurts in northeastern Utah.

You can take spectacular guided yurt trips in eastern Idaho through Teton Backcountry Guides. However, going unguided here requires route-finding skills and backcountry experience that’s likely beyond most first-time hut trippers. Same goes for the guided trip to the Bell Lake Yurt in southern Montana, where going unguided requires previous hut-tripping experience.

Other notable hut systems include the Sierra Club’s own Keller Peak Ski Hut in Southern California and the Peter Grubb and Bradley Huts in Lake Tahoe (booked through the Clair Tappaan Lodge), the huts run by the Mount Tahoma Trails Association near Washington State’s Mount Rainier National Park, and the Appalachian Mountain Club’s Carter Notch, Zealand Falls, and Lonesome Lake huts in New Hampshire’s White Mountains. (Depending on conditions, snowshoeing or winter hiking may be your preferred means of transport here.)

Huts make for cozy backcountry havens.

What Should I Bring?

Huts are equipped with kitchens, firewood, sleeping mattresses and pillows, an outhouse with a pit or compostable toilet plus TP, and photovoltaic lights. Many also have a selection of books and games, and some even provide a basket of slippers to wear at the hut. A smattering of huts even have the luxury of a wood-burning sauna.

In addition to a waterproof/breathable ski shell and pants, plus insulating layers, you’ll need some lightweight clothes to wear inside (I generally bring a T-shirt and leggings—huts heat up quickly when the woodstove is blazing), packable shoes or slippers, a toiletry kit, and a sleeping bag. I like to bring my own pillowcase too. Don’t forget a small first-aid kit, head lamp (for finding your way to the outhouse at night and reading in bed), and whatever book you’ve been meaning to find time to devour. Plus, of course, food. To carry everything comfortably, you’ll want a backpacking pack.

As with any backcountry mountain outing in winter, make sure to have an avalanche beacon, probe, and shovel. There may be minimal avalanche danger on the trail in to a hut (the routes to the 10th Mountain huts, for example, have been deliberately routed to minimize slide hazard), but if you want to ski or explore during your trip, you’ll need that safety equipment, along with the knowledge of how to use it.

One thing you can’t bring? Your dog. Because you’ll be relying on snowmelt for water, and dogs infamously create yellow snow, they’re not welcome at most huts.

How Will I Get There?

Most hut trippers use alpine touring or telemark skis, equipped with climbing skins, for access. Other good methods are splitboards (for snowboarders) or snowshoes. Yes, cross-country skis are an option, but if you’re able to navigate the often twisty, turny trails to a hut on those skinny boards while wearing a heavy backpack—especially on the way out, when the route is mostly downhill—you’re a much braver adventurer than I am.

Most hut trippers use alpine touring or telemark skis, equipped with climbing skins, for access. Other good methods are splitboards (for snowboarders) or snowshoes. Yes, cross-country skis are an option, but if you’re able to navigate the often twisty, turny trails to a hut on those skinny boards while wearing a heavy backpack—especially on the way out, when the route is mostly downhill—you’re a much braver adventurer than I am.

Members of your group should be familiar with backcountry winter travel, and at least one person should know how to route-find. Be sure to have a good topographic map of the area and a compass. A hut will have a designated route for access (and sometimes more than one from different trailheads), but markings will vary. Trails to the 10th Mountain system huts, for example, are well marked with blue diamonds on trees, but in a snowstorm, visibility can deteriorate.

Plan to leave from the trailhead early in the morning. Given the exertion required to skin uphill while carrying a backpack, reaching a hut often takes longer than you think. And if it snowed heavily the previous day, allow extra time for breaking trail. Early on in my hut-tripping career, some friends and I set out for the Skinner Hut, which, at almost 11 miles in, is notoriously the hardest one to access in the 10th Mountain system. It had snowed at least a foot overnight, which meant we had to break trail the whole way, and we started too late—at 10 A.M.—from the trailhead. By the time darkness fell (it was January, so days were still short), we were only about seven miles in. Not wanting to risk navigating at night, even by head lamp, we dug a snowcave and spent a wet, miserable, shivering night there before continuing to the hut the next morning. It was an experience I’ve made certain never to repeat.

And if getting to a hut on your own sounds too daunting, hire a guide. Most hut websites include links to local guide services that run trips.

Eat and Drink Well

I used to go on a lot of hut trips with my friend Sean when he lived in Colorado. In addition to getting in as many backcountry ski laps as possible, Sean loved to live large when it came to making hut meals: king crab legs, filet mignon, jambalaya, stuffed French toast. He brought it all in, and more. I’ll never forget the looks on the faces of two guys we once shared a hut with when they saw our dinner feast, then looked back sadly at their little packets of freeze-dried food. They were on their first backcountry ski trip and hadn’t realized that the hut would have a fully stocked kitchen with cookware and dishes, propane burners, and a wood-fired oven.

There’s a happy medium between Sean’s lavish approach (he used a mountaineering sled to hold everything) and that of the hut rookies we encountered. I recommend taking a backpacking approach to how you carry in your food—for example, eliminate extra packaging, put small amounts of cooking oil or whatever liquids you may need in plastic containers, and transfer wine to water bottles. But bring as much fresh meat, cheese, and/or veggies as you can comfortably carry; most huts have a “cold storage” area that functions like a natural refrigerator. And you’ll be able to prep most your food at the hut too; just be ready to negotiate counter space with hutmates.

The system that’s worked well for friends and me is to delegate breakfasts and dinners to share among group members, with an understanding that everyone is on their own for lunches and snacks. We also like to have a different crew wash dishes than the one that cooked the meal. Huts come equipped with dish buckets, soap, and bleach; putting a capful of bleach in the rinse water is highly recommended.

Huts have large metal pots for collecting snow and melting it on the woodstove. You’ll find a shovel outside for collecting snow; scout a clean-looking area at least 25 feet or so from the hut in which to dig. This will become your water for drinking, cooking, and washing dishes. Most people prefer to treat snowmelt before drinking it, either with a water filter they’re brought along, or by boiling.

Be a Good Hutmate

Backcountry living may be rustic, but there are still guidelines for hut etiquette:

Help with chores. The firewood box needs to be restocked, kindling split, snow buckets refilled for meltwater, decks shoveled, and dishes washed. It’s oh-so-tempting to settle in by the woodstove with a good book or a game and a mug of hot tea when you’re not out skiing, but pitch in a hand first, whether it’s to help out others in your own group or those you’re sharing the hut with.

Keep it together. Even if your home has a perpetual post-cyclone vibe, try to consolidate your belongings at the hut into a relatively small footprint. Not only is it nice to give your hutmates space for their own stashes, but it’ll also make it easier for you to keep track of gloves, goggles, and other accessories. You don’t want to be halfway down the trail home and realize you left your contact lenses behind.

Keep the floors dry. Take off your ski boots right inside the door and change into your hut slippers or shoes so you don’t track snow around inside. Then carry your boots over by the woodstove to warm them up and dry them out.

Know when it’s time to pipe down. One of the nicest times at a hut is in the evening, as people swap stories over dinner, engage in heated games of Hearts or Scrabble, or share sips of brandy by the fire. But when others start to shuffle off to bed, remember that your hutmates may not want to snooze off to you describing your most memorable hikes of the past year to the other night owl who’s still up. Likewise, if you’re an early riser, go ahead and restoke the fire in the morning, but leave the wood chopping, snow shoveling, or other noisy chores until most everyone else is onto their morning coffee.

Know when it’s time to pipe down. One of the nicest times at a hut is in the evening, as people swap stories over dinner, engage in heated games of Hearts or Scrabble, or share sips of brandy by the fire. But when others start to shuffle off to bed, remember that your hutmates may not want to snooze off to you describing your most memorable hikes of the past year to the other night owl who’s still up. Likewise, if you’re an early riser, go ahead and restoke the fire in the morning, but leave the wood chopping, snow shoveling, or other noisy chores until most everyone else is onto their morning coffee.

Pack it all out. The huts may seem homey, but there’s no trash collection. There are trash bags, however. Double bag your group’s trash to prevent leakage, secure the bag inside or outside of your backpack, and take it with you. That goes for uneaten food too. You may think you’re doing a favor by leaving your leftover pack of bacon or sticks of butter for the next hut users, but those extras tend to clutter up the kitchen area and can attract mice. An unopened bottle of wine, however? By all means leave it for the next group, who will likely toast you with gratitude.

The Magazine of The Sierra Club

The Magazine of The Sierra Club