Modern Noah Wants to Photograph the Animals. All of Them.

Joel Sartore is building a Photo Ark. It’s up to us whether the glorious, noble, and just plain weird creatures aboard it will ever get off.

Remember the Pioneer Plaque? It was a gold-anodized aluminum sheet attached to the 1972 Pioneer 10 spacecraft, showing a naked (Caucasian) man and woman and a schematic of the solar system for the edification of any extraterrestrials who might come upon it. Who knows? Maybe, like the aliens in Arrival, they’ll drop by to help us out.

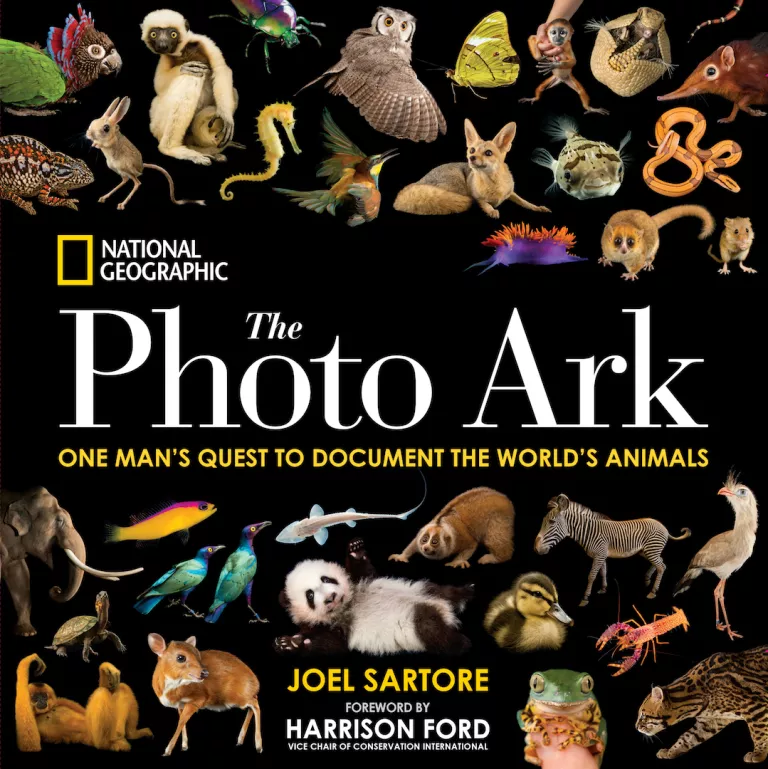

A similar impetus is behind National Geographic photographer Joel Sartore’s magisterial The Photo Ark: One Man’s Quest to Document the World’s Animals (National Geographic, 2017, $35). “I think of myself as an animal ambassador, a voice for the voiceless,” he writes. “People can’t save what they don’t know exists.”

Sartore has contributed to National Geographic for a quarter century, but it would not be an exaggeration to say that the Photo Ark project—which he estimates will take another 25 years—is his life’s work. It began in 2005, after his wife was diagnosed with breast cancer (from which she later, happily, recovered). He suddenly had to confront mortality and the value of his remaining days. The project he devised was to document the world’s 12,000 captive species with formal studio portraits; the proboscis monkey he shot at the Singapore Zoo last May was number 6,000. (In one of many clever pairings in this book, the ape appears opposite a pair of African spoonbills, whose bills mirror its impressive schnoz.) The animals, mostly from zoos but some in captive-breeding programs, are shot against plain white or black backgrounds—an M.O. that has the virtues of realizability (shooting 12,000 creatures in their native habitats would take far longer than one photographer’s lifetime) and democratization. “It levels the playing field,” says Sartore. “The tortoise counts as much as the hare, and a mouse is every bit as magnificent as a polar bear.”

And indeed it is. The St. Andrew beach mouse grooming its whiskers fills the page as much as the mandrill on the facing page, its hand raised to its mouth in a similar gesture, although not to groom. Rather, it looks for all the world like astonishment: Sartore notes that the ape “is likely reacting to seeing itself for the very first time, seeing its reflection in the glass filter on the front of my lens.” The equal-weight protocol even extends (occasionally) to invertebrates, like the quizzical springbok mantis (mirrored by a correspondingly curious arctic fox), and the nightmare-inducing hairy jaws of a wolf spider. Insects generally benefit from being viewed at a smaller scale. A magnificent spread juxtaposes nine extraordinarily varied grasshoppers and an equal number of phantasmagoric shrimp; a circle of oblong-winged katydids—yellow, chartreuse, orange, pink—look like long-legged candies. Go home, evolution—you’re drunk.

When your project is to display the panoply of life on our planet, strange creatures are unavoidable. Thus an entire chapter is devoted to “Curiosities,” like a dragonfly with wings apparently made of stained glass and the hideous red-headed uakari, a New World monkey that looks like a choleric talk-show host on Fox. But The Photo Ark has a deeper, more serious purpose, because saving the world’s creatures from the modern deluge of habitat loss and climate change is going to take a lot longer than 40 days and 40 nights. Veteran National Geographic writer (and sometimes Sierra contributor) Douglas Chadwick contributes a customarily eloquent and moving essay about the extinction crisis and our responsibility in it:

To continue extinguishing species in an eyeblink of geologic time is to heedlessly delete file after file, volume after volume, in nature’s genetic library. Permanently. This isn’t merely shortsighted. Apart from punching the nuclear launch button, it has got to be about the dumbest, most counterproductive thing an animal that prides itself on being intelligent could do.

Sartore isn’t about to let us wallow in despair, though. His book is sprinkled with the stories of conservation heroes, and concludes with “Stories of Hope”—amazing creatures that could have joined the dodo and thylacine but somehow held on and, in some cases, flourished anew. After a successful captive-breeding program, the California condor now flies freely again in the central part of the state and perhaps soon among the redwoods again. The banning of DDT in 1972 allowed the Peregrine falcon to make a comeback, and now it has found new habitat among the skyscraper canyons of cities like New York and San Francisco.

But hope is famously not a plan. The Mexican gray wolf recently flirted with extinction, and while captive-breeding and reintroduction programs have increased its numbers, President Donald Trump’s threatened “great, great wall” could bisect its habitat. Whether the Sumatran orangutan—which is fast losing its native forests to logging and palm oil plantations—is consigned to the photographic ark forever is up to us. “This orangutan was quite tame,” recalls Sartore. “I remember being in the room with her as she posed on white seamless paper. I kept wondering what she was thinking behind those eyes.”

The Magazine of The Sierra Club

The Magazine of The Sierra Club