Material Guy

Damon Carson is helping American industry be more resourceful one concrete block at a time

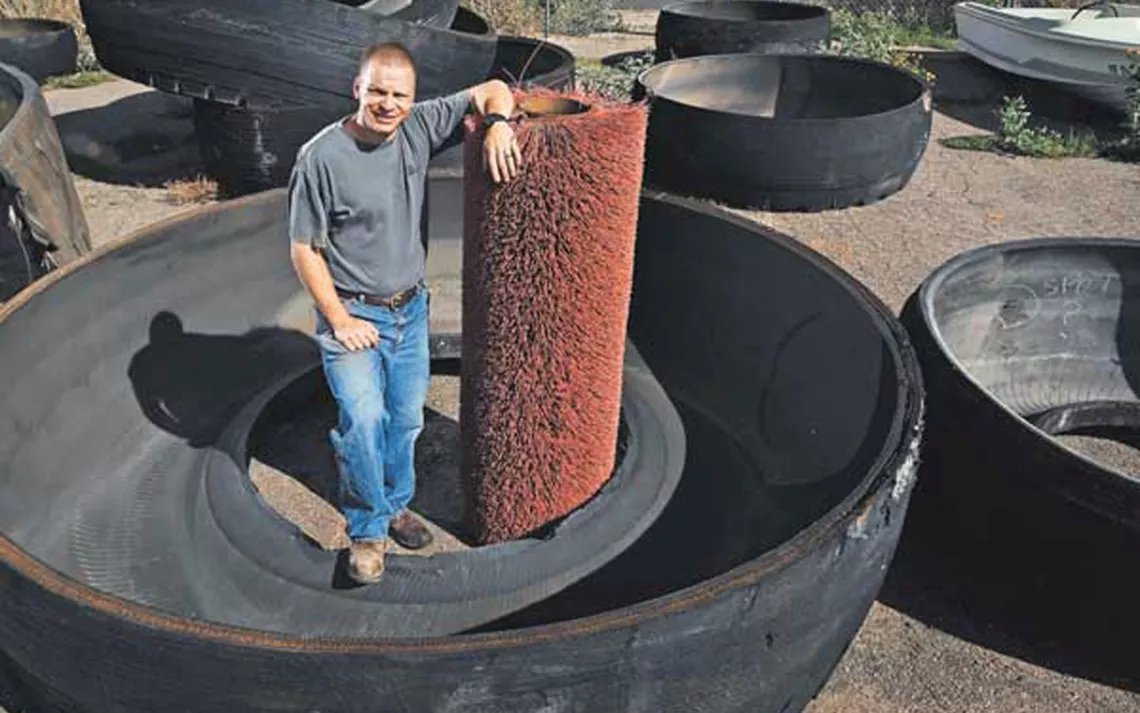

Damon Carson, founder of Repurposed Materials

|Photos courtesy of Repurposed Materials.

In the fall of 2010, Damon Carson was making a living restoring and refurbishing coin-operated kiddie rides. Then an airbrush painter he worked with gave him some offhand advice that changed the course of his career: “If you ever get a chance to buy one of those old advertising billboards that you see along the side of the road,” he told Carson, “you ought to buy one. They make a great drop cloth for painting.” This was Carson’s ah-ha moment. He made a few calls to outdoor advertising companies, bought 20 old billboards, and then sold them for a profit.

Old billboards are usually just thrown away, adding approximately 10,000 tons of billboard fabric to U.S. landfills annually. But as Carson has discovered, they can be reused not only as drop cloths but also as hay covers, pond liners, and even slip n’ slides. He’s sold 10 to a U.S. Army Ranger battalion to be used as curtain walls in a training maze.

Back in 2010, Carson knew he was onto something, but he wasn’t serious about it at first—buying and selling billboards was just a way to make a little extra cash, or as he calls it, “entrepreneurial screwing around.” Then about six weeks after he sold his first billboard, he found himself talking with one of his business associates about rubber. He searched online that evening, stumbled on conveyor belting, and bought and then resold a couple of used rolls. Animal barrier, garage flooring, railroad spill containment—it turns out there are a lot of secondary uses for conveyor belting.

Back in 2010, Carson knew he was onto something, but he wasn’t serious about it at first—buying and selling billboards was just a way to make a little extra cash, or as he calls it, “entrepreneurial screwing around.” Then about six weeks after he sold his first billboard, he found himself talking with one of his business associates about rubber. He searched online that evening, stumbled on conveyor belting, and bought and then resold a couple of used rolls. Animal barrier, garage flooring, railroad spill containment—it turns out there are a lot of secondary uses for conveyor belting.

Sign up to receive Sierra News & Views

Get articles like this one sent directly to your inbox weekly.

With this action you affirm you want to receive Sierra Club communications and may vote on policy designated by the Sierra Club Board.

In 2011, he officially launched his company, Repurposed Materials. Since then, he’s hired a staff of 15. The company is headquartered in Denver but runs five lots around the country. He and his employees are always on the lookout for products that are generic, versatile, and adaptable. (Carson says these three adjectives so fast, they sound like one word.) Stuff made out of basic materials like wood or plastic or glass can easily be repurposed for other uses, though usually Carson has no idea what those other uses will be until a customer calls him up. Through the conduit of his company, floor from a gym has become wall siding; bowling alley lanes have been fashioned into tables and chairs; a firehose has been transformed into a hammock; and a pool cover has been turned into a kennel shade. In 2016, his company diverted more than 7,000,000 pounds from landfills.

The job keeps surprising him. About a year ago, he purchased two semi loads of concrete from Comcast. “I thought maybe a cattle rancher would buy them,” Carson says. But a trucking company bought them all within two weeks. That particular company often shipped loads to Wyoming, a sparsely populated and windy state. On high-wind days, trucks that weren’t carrying a lot of packages would blow over, so the shipping company bought the concrete slabs to add extra weight to the truck beds. “I could have stayed up until 3 A.M. seven nights in a row, and I would have never thought of that,” Carson says.

Despite its potential utility, a staggering 375.3 million tons of concrete is dumped into U.S. landfills each year. Waste like this makes Carson feel sick. He’s always been a reuse kind of guy. He drives a used car and buys used clothing. He grew up in Kansas where the resourcefulness of rural America permeated everyday life. He was fascinated by how farmers would use oil field pipes to build corrals and railroad ties to build fence posts.

Recently, he received a call from a contractor working with the U.S. Coast Guard. They had ordered an industrial barrier wall to be erected somewhere along the coast, but it came in the wrong color—bright orange instead of burnt orange. “They rejected it because of color,” Carson says in disbelief. “It would be one thing if it were for a fashion runway in New York City, but we’re talking about a barrier wall that nobody’s going to see.”

According to Carson, this is not uncommon. About a month ago, someone contacted him about geofoam, a product that’s used in highway construction. Before it was to be installed, it was sitting in a construction yard where it got some minor scrapes. All of it—25 semi loads' worth—was rejected, even though once the material is in place, it’s buried underground and out of view. “One of my favorite lines is, ‘Abundance is the enemy of resourcefulness,’ Carson says. “This is the land of abundance, so Americans aren’t very resourceful.”

Randy Weikle gets the repurposing mentality. He and his wife are building a cabin in Blairsville, Georgia, and he keeps a careful eye on Carson’s inventory. He’s purchased hockey glass to use for the second-floor balusters, sliding material and particle board for the decks, artificial turf for the dog run, bleacher wood for shelves in the greenhouse, and a cargo parachute to use as a shade structure. “We have had phenomenal luck with the stuff that we find at Repurposed Materials,” he says. “It’s in great shape. We find great uses for it, and it’s enriching the cabin.” He estimates that buying used materials for the cabin’s construction has saved him roughly $50,000.

Carson is not big on governmental regulation, but he thinks making landfills more expensive might help solve the waste problem in America. “If it were $105 a ton in some landfills rather than $35 a ton, it would make people pause and maybe do a Google search instead of just calling waste management.” One way or another, entrepreneurs need to be incentivized not to waste. “Our company has grown because our model is economically viable,” he says. “We’re keeping a lot of stuff out of the landfill, but we’re standing financially on our own two feet.”

Watch Damon Carson talk about Repurposed Materials:

The Magazine of The Sierra Club

The Magazine of The Sierra Club