Help Songbirds Migrating North Avoid Collisions

Opportunities abound for bird-loving citizen scientists

Photo by VictorTyakht/iStock.

Every year starting around March 15, migratory songbirds begin their arduous journeys back north to their summer nesting sites. These songbirds travel at night, navigating by the earth’s magnetic pull as well as through “maps” made up of constellations. They often unnoticed by anyone accustomed to seeing the V-formations of day-migrating geese and other shorebirds. Unnoticed, that is, until they collide with buildings.

Collisions are the second largest killer of birds in the United States after cats, accounting for somewhere between 100 million and 1 billion deaths per year, with the likelihood of collision at its highest during migrations. That’s why every spring and fall, birding organizations and their bird-minded volunteers kick into action, prowling just after dawn through cities and towns along the four major migratory flyways: the Atlantic, which stretches from the Caribbean to Baffin Island; the Mississippi, from Alabama to Manitoba; the Central, from the Gulf Coast of Texas to Canada’s Northwest Territories; and the Pacific, from Patagonia into the Yukon.

Like those who partake in Audubon’s Annual Christmas Bird Count, these volunteers are part of one of the planet’s most comprehensive citizen science projects. Such birders have multiple objectives: amassing data for studies that analyze which “super collider” bird species are most at risk for building crashes, and determining the building types that attract the greatest number of super colliders.

Their data is put to great use. New York’s NYC Audubon, for example, used 15 years’ worth of volunteer-accumulated data from its Project Safe Flight program to show that white-throated sparrows and common yellowthroats suffered the greatest number of impacts in the area. Citizen scientists working with Audubon societies in Atlanta,Texas, andMinnesota—and in Canada, via an organization called Fatal Light Awareness Program (FLAP)—input their findings into crowd-sourced, online databases that researchers can access. What’s more, NYC Audubon,Audubon Atlanta, and the Chicago Bird Collision Monitors consistently send out volunteers come migration time to monitor high-risk building sites—often glassy high rises located across from parks—for injured birds. Those they find, they bring to rehabilitators.

What causes the crashes? According to Joanna Eckles, a conservation program manager at Audubon Minnesota, the biggest culprit is light pollution. Bright lights can confuse birds, “trapping” them so they flap in circles until they die of exhaustion, or disorienting them to the point where they fly headlong into the glare. As the sun starts to rise, buildings that reflect trees pose a danger, too—tricking birds into thinking such reflections are in fact places to perch. Several Audubons use volunteer-collected data to beseech building managers to turn off lights during migration season, and to advise architecture firms on bird-friendly window treatments. While skyscrapers in cities are huge risks for migrators, according to Eckles, “Most birds are killed by our homes.” This includes low-rise structures in rural areas, as well as developments in suburbs. “That’s good news,” she says, “because it means this is a preventable problem.”

DIY solutions include turning out lights when they’re not in use, and swapping out porch bulbs for LEDs that point downward, reducing bird-luring glare. Decals can warn birds that they're not about to fly through empty space, and covering windows with screens or netting can lesson the impact when and if birds do crash into them.

FLAP Canada provides excellent resources for collision-proofing your home. But if you’re all hopped up to get out and volunteer, locate your local Audubon or contact Chicago Bird Collision Monitors to learn what citizen science opportunities they’re offering for bird enthusiasts this spring.

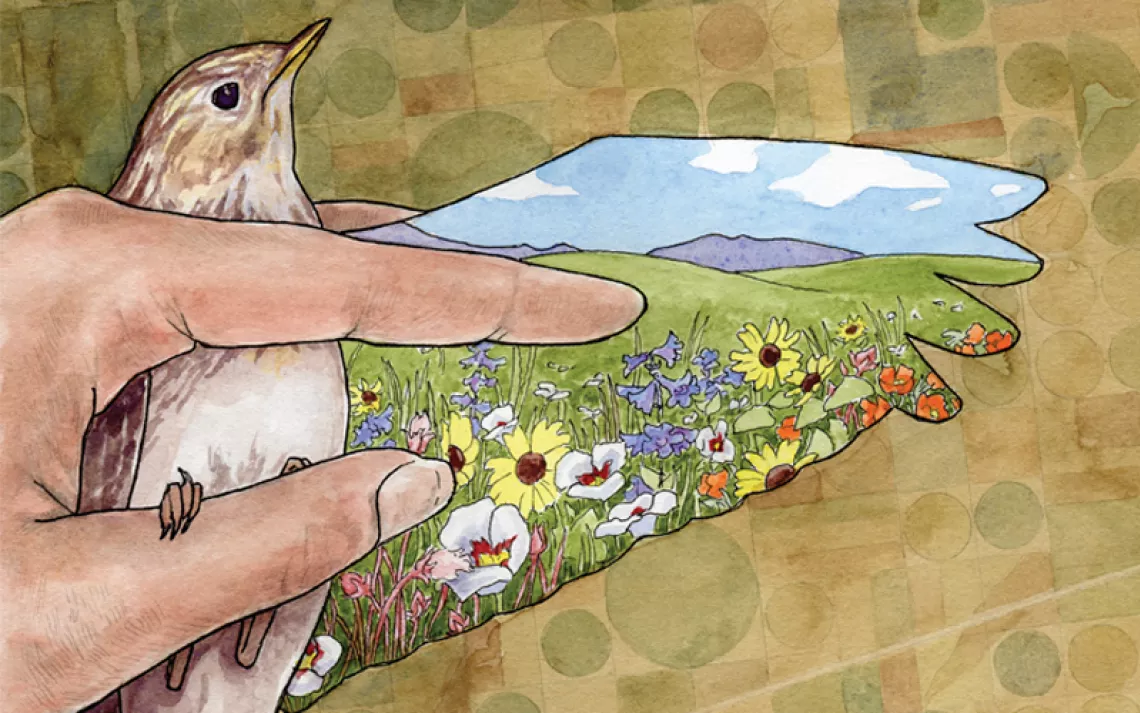

Another thing to keep in mind: Gardens are outdoor sanctuaries for birds, insects and other wildlife. Every spring, migrating birds visit citizen yards seeking nourishment from gardens, and places to raise their chicks. By adding native plants to one’s yard, balcony, container garden, rooftop or public space, anyone, anywhere, can not only attract more birds, but give them the best chance of survival in the face of climate change and urban development.Check out Audubon’s Plants for Birds public online database, through which anyone nationwide can access a list of native plants that benefit their favorite local bird species, by just typing in their zip code. Live near chickadee populations? Help them out by planting some birch. Attract hummingbirds with honeysuckle vines. Type in your own zipcode to learn more.

The Magazine of The Sierra Club

The Magazine of The Sierra Club