A Dynasty at Risk

Another dismal population count puts the monarch butterfly closer to extinction

Photo courtesy JHVEPhoto/iStock

Iconic is one word that comes to mind: the bright orange and black lattice wings, flecked with white, fluttering through fields on bright summer days. Even from a young age, most Americans can recognize the monarch butterfly—the aptly named invertebrate considered to be the king of all rhopalocera.

A glimpse of the monarch, however, has become rare. The only butterfly in the world with a birdlike, two-way migration is more scarce than ever before, according to biologists’ latest tally.

A study published in Scientific Reports last March found that the population of eastern monarchs had dropped by 80 percent in the last decade. Now, with the 2016-17 wintering season coming to a close, the butterfly’s population has declined by one third since the 2015-16 count.

“The numbers of monarchs have been steadily declining for the last decade and a half, and that has been verified again this winter with low counts from the last winter,” says Doug Gurian-Sherman, the director of sustainable agriculture at the Center for Food Safety. “We think the evidence is quite strong and is the basis of serious concerns for the migrating population of monarchs. No other insect makes a migration comparable to monarch butterflies.”

Monarchs are divided by the Rocky Mountains, with the western monarchs living west of the Rockies and eastern monarchs on the other side of the range. Eastern monarchs are unique in that they have a multigenerational migration between their winter home in central Mexico and summer breeding grounds in the northern United States and southern Canada. It is the fourth-generation monarchs that make the 1,200-to-2,800-mile trip, after which they hibernate for six to eight months before the process begins again. Most other adult butterflies only live two to five weeks.

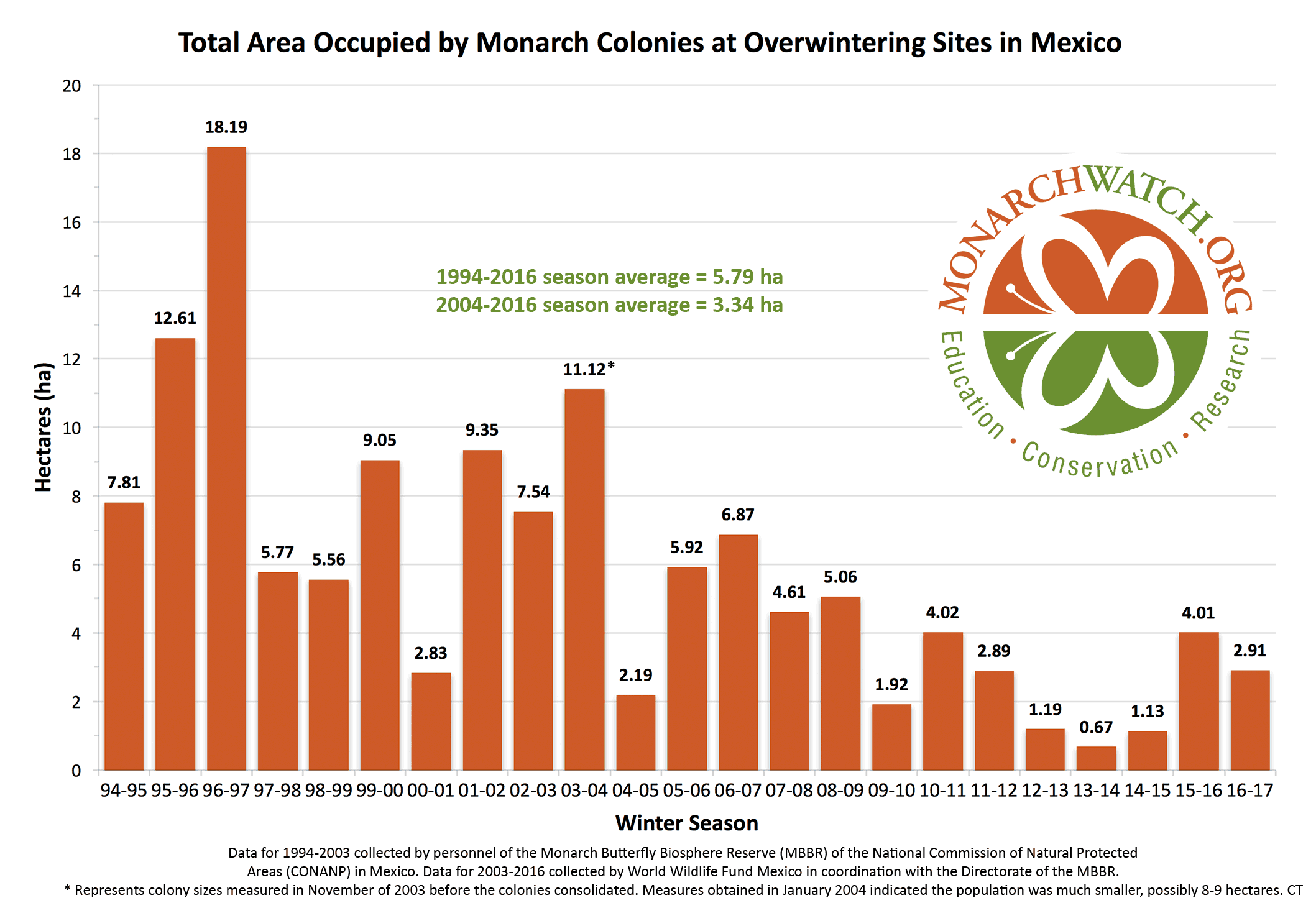

The count is done every year by the World Wildlife Fund Mexico as the butterflies winter in the oyamel fir forests in the Trans-Volcanic Mountains west of Mexico City. Counting every insect is impossible, so they are measured by hectare, with 37.5 million butterflies estimated to be in one hectare. This year, roughly 109 million monarchs were counted over 2.91 hectares. Last year, researchers recorded 4.01 hectares and 150 million monarchs. The highest count ever recorded was in 1997 with 18 hectares and 682 million butterflies. That is, the population of eastern monarchs has dropped by about 85 percent in the last 20 years.

The western monarchs are experiencing a similar trend, with 298,464 monarchs observed this winter. In the late 1990s, 1.2 million were recorded, according to Xerces Society.

With this continuing decline, it’s estimated that the eastern migrating monarchs have anywhere from an 11 to 57 percent of “quasi-extinction” over the next 20 years.

“Monarchs are kind of the poster child of pollinator declines because they're so beautiful and recognizable,” says Tierra Curry, a senior scientist at the Center for Biological Diversity. “Protecting habitat for them would protect the habitat for a large variety of lesser known pollinators.”

Monarchs face three interwoven threats: habitat loss, large-scale corporate farming, and climate change.

On one end of the spectrum, logging in central Mexican forests is depriving the insects of their winter home. As Curry notes, the butterflies are attracted to the woods for hibernation because the trees act as an insulator from winter temperatures. Without the trees, microclimates can drastically change and leave the insects vulnerable to the cold. In 2002, a winter storm killed 220 to 270 million of the creatures. Curry and the Center for Biological Diversity report that the mortality rate from that storm may have even been as high as 500 million.

Meanwhile, there has been a rapid decline of milkweed in the central United States, where the migrating butterflies lay their eggs for the next generation of monarchs. Milkweed, especially common milkweed, is the only source of food for the larvae and caterpillars.

“For as long as anyone has looked, populations of this milkweed have existed in the Midwest, in the corn belt and elsewhere, and has provided food for these monarchs,” Gurian-Sherman says. “What happened in the mid-90s was the introduction of genetically engineered crops that were designed to be resistant to the herbicide glyphosate. That’s important, because it increased use of herbicides overall, but it is also highly effective in killing milkweed.”

Glyphosate, also known as Roundup, is the most commonly used herbicide in the United States. In 1996, Monsanto launched Roundup Ready genetically engineered herbicide-tolerant soybeans and corn, which are now often used throughout the U.S. agricultural sector. As noted in the Scientific Reports article, 94 percent of soybean acreage and 89 percent of corn acreage is genetically modified Roundup Ready.

“Historically there have been billions of monarchs when there were a lot more natural and prairie areas,” Curry says. “When the vast majority of corn became genetically modified to herbicide-tolerant corn, it drastically reduced the amount of milkweed. These are corn deserts now where pollinators and monarchs are not being able to use those fields.”

Gurian-Sherman says that with 98 to 99 percent of milkweed being eradicated, there is not enough of the plant to sustain the generational cycle. Neonicotinoids, the pesticide implicated in the decline of bees, may also play a role in the monarch decline. Although neonicotinoids’ effect on monarchs is still being studied, Curry says it does kill young butterflies, and it can be absorbed into plants, potentially contaminating the remaining milkweed.

Milkweed abundance can also be affected by climate change. Like the oramel fir in Mexico, milkweed is highly susceptible to drought. Large swaths of the insects’ range in the United States remain under drought warnings, from abnormally dry to pockets of moderate and severe drought. Some areas north of the monarchs’ winter home in Mexico are becoming too hot for the larvae and caterpillars.

Given this grim news, what can be done to help boost monarch butterfly populations? Both Curry and Gurian-Sherman argue that the reworking of the U.S. agricultural system is necessary for preserving the species. Moving toward sustainable farming with a focus on habitat restoration and prairie strips would give monarchs a fresh chance.

Another option is to get monarchs listed under the Endangered Species Act, which would help create mandatory programs that work with farmers and other industries to find best practices to conserve the species. In 2014, the Center for Biological Diversity, the Center for Food Safety, the Xerces Society, and monarch scientist Dr. Lincoln Brower petitioned the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service to list the butterfly as threatened under the act. The Fish and Wildlife Service has until 2019 to decide on protection. In the meantime, the current political forecast further clouds the future for these insects.

“Clearly some of the proposed and newly approved cabinet positions have seemed to be quite hostile toward the mission of protecting our environment,” Gurian-Sherman says. “While we hope they act in the best interest in the way of our society and environment, including these rural [farming] communities, their record says otherwise. The motivation is profit, not protecting the environment.”

The Magazine of The Sierra Club

The Magazine of The Sierra Club