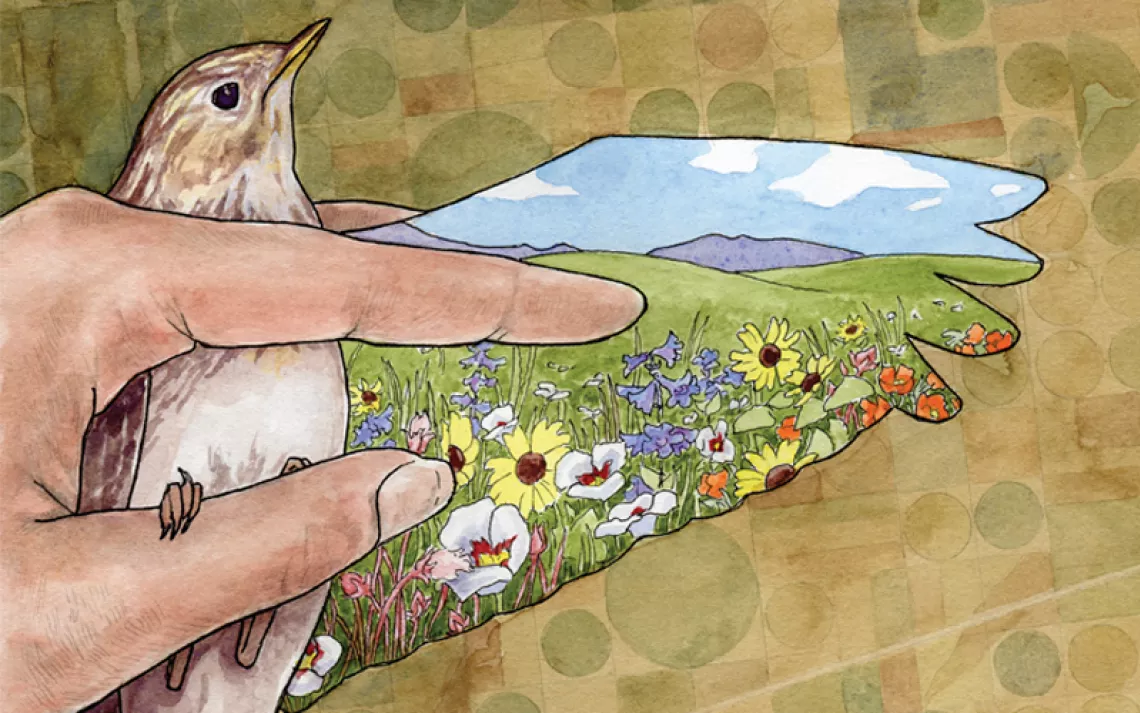

For the Birds

A new mapping tool helps steer people away from stressed-out wildlife

Photo by kenileed/iStock

Jim Oehler likes to take morning walks along the trails in a popular preserve in Hollis, New Hampshire. One day last fall, he inadvertently flushed up four wood ducks. As a wildlife biologist with the state’s Fish and Game Department, Oehler understood better than most people how stressful that interaction could have been for the waterfowl—and how his seemingly benign behavior was a factor in that stress.

“We need to get people outside to enjoy nature—the physical and emotional benefits of nature,” he says. “But we need to do it in a balanced way so that wildlife can thrive. And outdoor recreation can have an impact on wildlife—their abundance, distribution, and presence in the woods.”

Encounters between humans and wildlife are increasingly common today, especially as more users hit the trails in response to pandemic-related closures of indoor spaces. A study published in April by the Connecticut Trail Census found that average trail use increased by 77 percent at 13 of the state’s most popular multiuse trails in March 2020 compared with the previous year. A Pennsylvania Environmental Council study found that springtime trail use in 2020 started a full month earlier than usual, and that across the state people got outside in unprecedented numbers.

Whether they know it or not, trail users’ routine behaviors can stress wildlife. Seemingly innocuous encounters like a trail runner passing a pair of endangered Blanding’s turtles, a mountain biker riding through a flooded section of trail, a birdwatcher approaching a steep slope for a close look at a peregrine nest, or a horseback rider passing by a heron rookery can, each in their own way, discomfit wildlife.

Such encounters can prompt a range of reactions in animals, including increases in heart rate, temperature, and stress hormones, as well as behavioral changes that negatively impact their ability to forage. Run-ins with people can result in birds building fewer nests, laying fewer eggs, or leaving young chicks vulnerable to predation when adults flee from perceived predators. Combine these impacts with breeding season or harsh winter conditions, and it’s easy to see how even brief human interactions can have long-term consequences, such as a species that leaves an area and doesn’t return.

In an effort to address the consequences of human-wildlife encounters, last year Oehler and his team at New Hampshire Fish and Game began to develop a statewide tool that gives land managers information about wildlife when planning new trails. Trails for People and Wildlife applies habitat data to help landowners, conservation groups, and natural resource professionals decide not only where to build new trails but also where to reroute and decommission existing ones.

“People weren’t thinking about the impacts of trails on wildlife,” Oehler says. “They probably weren’t thinking it was an issue. That’s my perspective in dealing with different natural resource professionals.”

Oehler’s team first compiled an online map of conservation land labeled with existing trails, parking lots, kiosks, scenic overlooks, historic sites, bodies of water, and other key features. They then overlaid that map with five habitat criteria: wet areas, steep slopes, rare species, habitat edges, and special habitats.

Next, they generated a heat map in which shades of red indicate ecologically sensitive areas best left as undisturbed as possible, while shades of blue show areas that are ideal for trails because they’ll impact wildlife least. The mapping tool allows trail planners to follow the blue colors to route trails away from rivers, streams, and wetlands that are home to waterfowl, wetland birds, and turtles; to avoid steep slopes where peregrine falcons, bobcats, and rare small-footed bats raise young; to route trails along habitat edges to protect bobolinks and eastern meadowlarks in grassland, and New England cottontails or eastern whip-poor-wills in shrubland; and to avoid habitats sensitive to disturbance such as pine barrens and rocky ridges. Oehler says that after a heat map is generated, one of the final and most important stages of the process is decidedly analog: “Boots on the ground.”

While other states have incorporated habitat criteria into their trail planning, New Hampshire is the first to apply it to GIS modeling. “Those same principles, like avoiding wet areas, have been deployed in other states such as Colorado. But they didn’t create that mapping model that you could overlay on,” says Rachel Stevens, a wildlife ecologist for the Fish and Game Department and stewardship coordinator with Great Bay National Estuarine Research Reserve, which initiated the project. Public lands officials in Vermont and Massachusetts have expressed interest in developing similar tools for their states.

Some private conservancies in New Hampshire have already started using the mapping tool. With more than 1,500 acres, Stonehouse Forest, in Barrington and Nottingham, is the largest undeveloped parcel in Barrington. Three years ago, it featured more than 10 miles of single-track trails and wooded primitive roads. Portions of them crossed wetlands and ponds, including the well-visited Round Pond and Little Round Pond on the northern part of the property.

Using the mapping tool, forest managers decided to maintain more than seven miles of trail, create three new sections of trail totaling about one mile, and decommission 3.6 miles of trail. “We created a new portion of trail that lets people go along the southern edge of Round Pond and Little Round Pond, see the open water and waterfowl, then redirects them south,” says Deborah Goard, stewardship director for Southeast Land Trust of New Hampshire, Exeter, which acquired the property in 2017. A section of trail that went “straight through wetlands” on the southern portion of the property was decommissioned, she says, adding, “it was all red on the heat map.”

South of Stonehouse lies a 1,100-acre parcel owned by the Harvey family. The family has allowed public recreation on 13 miles of trails and woods roads that wind through palustrine wetlands buffered by forested uplands and beaver-influenced ponds supporting a great blue heron rookery. “The family has allowed people to use it—hunting, hiking, mountain bikes, all of that—for, like, forever,” Goard says.

The Southeast Land Trust has also used the mapping tool to redesign trails on the Harvey property, which has an extensive network of water features, including vernal pools that attract breeding species such as fairy shrimp, spotted salamanders, and wood frogs. Trails in these areas often flood and show up on the heat map as orange and red. As a result, the land trust reduced trails in these high-impact areas by 70 percent and steered users to higher elevations. The trust also more clearly designated which trails were appropriate for specific activities such as hiking, mountain biking, and horse riding. “We can take people to a different location on the property, still enjoy the views, and still walk through the forest, but lessen the impact on the water quality and the animals using the wetlands and the areas around it,” Goard says.

Goard sees the tool as a way to balance users’ love of trails with limited resources for maintaining them. “As a land manager who manages land that’s highly used like these two properties, we don’t have the time or resources to go out and get all the scientific information from our properties,” she says. “To have something that we can easily and quickly input our trails into, and have snapshots that help us take wildlife into consideration with everything else is great. I’ve been telling everyone to use it.”

The Magazine of The Sierra Club

The Magazine of The Sierra Club