February Astronomical Highlights: Meteors and the Dawn of the Planets

What doesn’t happen this month is just as interesting as what does

Photo by VitaliyPozdeyev/iStock

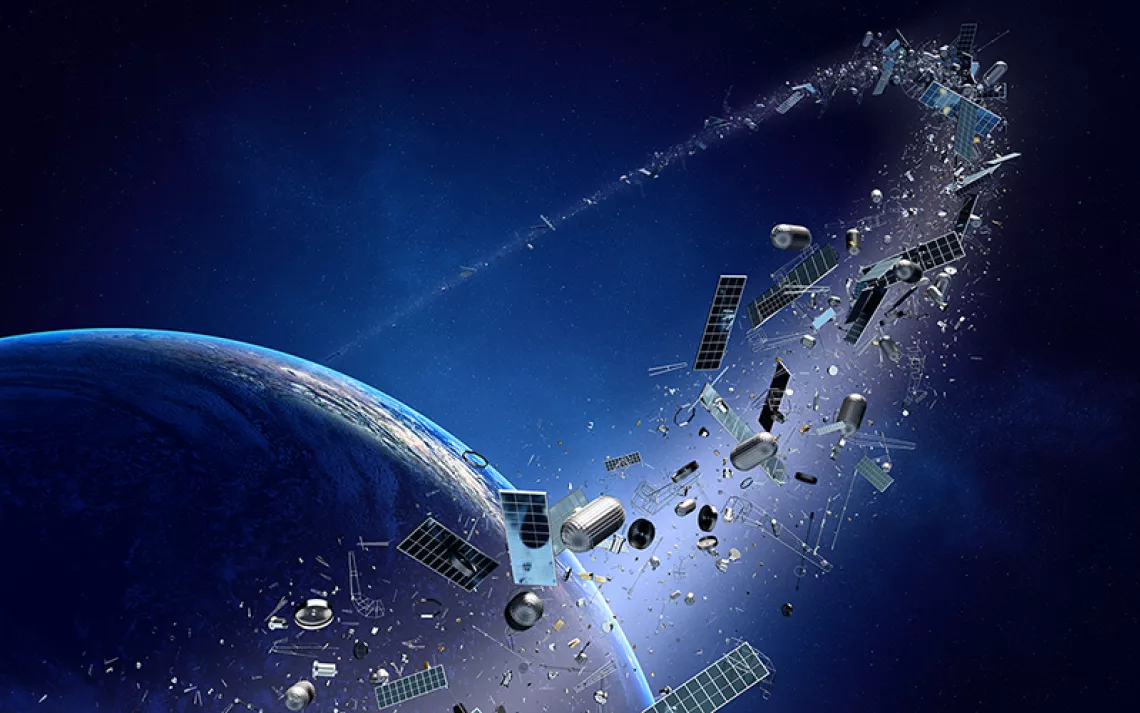

News junkies who can remember back to July 2002 will breathe a sigh of relief when February 1 has come and gone without incident. That’s because 17 years ago, a newly discovered two-kilometer-wide Near Earth Object named 2002 NT7 looked like it might impact Earth on this date. NASA went so far as to list it on the Torino Impact Hazard Scale, only to remove it a few days later after its orbit was refined and the all-clear was given. If you’re nervous that maybe the subsequent observations got it wrong and that a dangerous object is still hurtling toward us, you’ll be happy to know that 2002 NT7 already crossed Earth’s path back in January. Newly discovered objects have been added to the Torino Scale every year (there were four in 2018), but all were eventually removed after further observations and calculations showed them steering clear of our planet.

Small, nonhazardous objects strike Earth’s atmosphere all the time, producing the flashes and streaks of light we see as meteors. These bits of solar system debris are usually about the size of dust or pebbles and burn up completely in a matter of moments. The moon can also be a target of these, and just such an object was recently seen during the total lunar eclipse on January 20/21. As the onset of totality began, various astrophotographers captured a tiny prick of light on the left side of the moon. Unlike Earth, the moon doesn’t have a protective atmosphere, so the fooball-size object would have impacted the moon and created a possible crater of about 30 feet, which astronomers are now searching for.

Mars Leads to Uranus

The best time to spot Uranus—one of the planets that is farthest from us in our solar system—is when it is near brighter and more easily identifiable objects. This will occur on February 12, when Uranus passes less than 1 degree from Mars. At magnitude 1, the red planet is 1.6 AU (astronomical units) from Earth, while Uranus glows at magnitude 5.8 and is 20.2 AU from Earth. A star glowing at the same magnitude is located a tiny bit farther from Mars. Magnitude 5.8 is considered within the range of objects you can see without optical aid, but you’ll need to observe from a location without light pollution, and your eyes must have adjusted to the dark.

If you’re having trouble figuring out which spot of light near Mars is the star and which is Uranus, the planet should have a little bit of a disk appearance that’s visible through binoculars or a telescope, and perhaps have a greenish-blue tint. You should just be able to fit reddish Mars in the binoculars' field of view along with Uranus, which is to the left and a little below Mars. You’ll find this pairing of planets in the southwest after it gets dark, drifting in the constellation Pisces. A half-lit moon in Taurus may add to the challenge of finding Uranus, by brightening the evening sky. The moon keeps Mars company on February 10 and will be full on February 19.

Dawn of the Planets

Mars is the only easy-to-spot planet in the night sky this month, but the morning sky hosts a lot of activity. In the early hours of February 1, you can find Jupiter, Venus, a crescent moon, and Saturn all strung out along the eastern horizon. The moon sinks to the far side of Saturn on the next morning before disappearing near the sun and re-emerging in the evening sky a few days later.

Venus falls closer to the horizon each morning, getting nearer to Saturn until February 18, when they are slightly more than 1 degree apart. The duo sits on one side of the Milky Way with Jupiter on the other. On the last two days of February, the moon again joins the morning scene, first pairing with Jupiter and then bridging the gap between the planets with the Milky Way as a background.

The Magazine of The Sierra Club

The Magazine of The Sierra Club