Cutting Trees to Save the Birds

How managing Maine’s “baby bird factory” can save eastern songbirds

Photo by Dan Zukowski

It’s a chilly, damp spring morning in Sewall Woods. The red oaks have begun to leaf out among the white pines, and a soundscape of songbirds plays in the tall trees. This 91-acre former dairy farm along the Whiskeag River in Maine has been designated as a demonstration forest by the Kennebec Estuary Land Trust, where landowners, foresters, and loggers can see that cutting a few trees actually helps bird conservation.

Active management of the state’s vast woodlands with an eye toward enhancing bird habitat is the goal of the Forestry for Maine Birds initiative, a collaboration of Maine Audubon, the Forest Stewards Guild, and state conservation agencies.

Populations of eastern forest birds have declined by 25 percent since 1968. Since 90 percent of Maine’s land, or 17.6 million acres, is forested, 90 different bird species come here each year to nest, mate, and raise future generations.

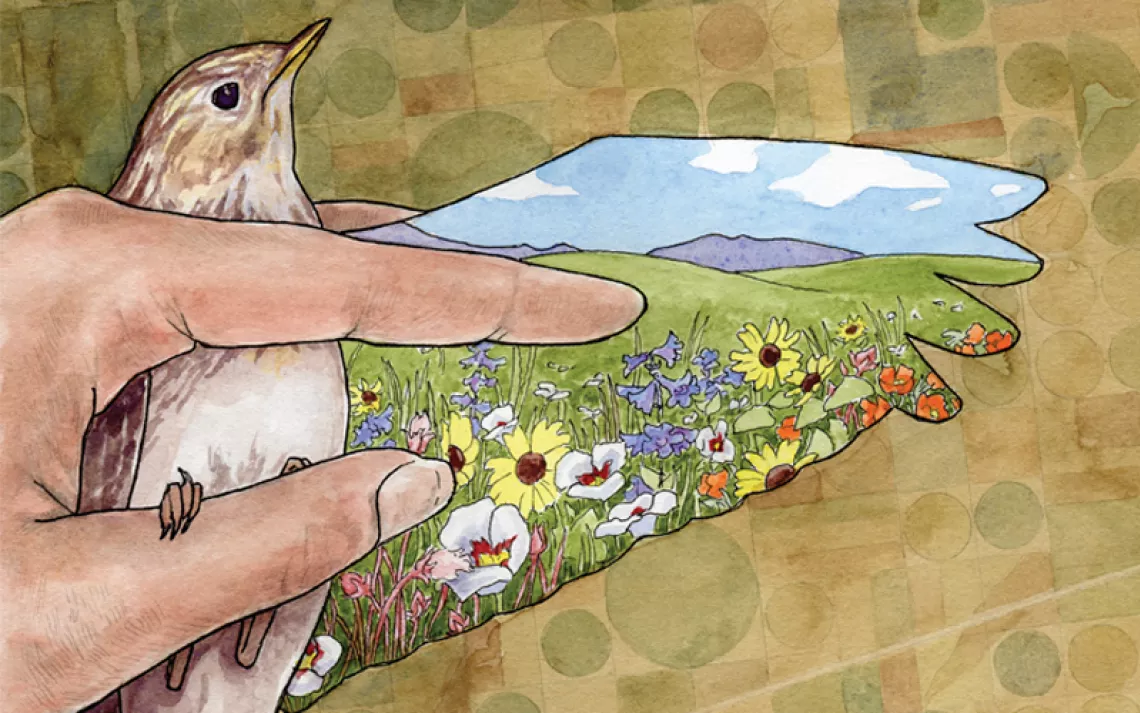

I meet Susan Gallo and Sally Stockwell, who are leading the initiative for Maine Audubon, at the Sewall Woods trailhead. “If you think about long-term population recovery, you need more baby birds,” says Gallo, a wildlife biologist. “And if you look at where the baby birds are produced, it's really Maine."

Maine Audubon identified 20 priority species, some of which make their presence known as we walk the Whiskeag Trail. We hear an ovenbird singing “teacher-teacher-teacher” and the plaintive song of the eastern wood-pewee. High above us, a male northern flicker attempts to charm an unimpressed female.

Gallo explains that healthy forests include a variety of vegetation. A dense understory allows birds to hide from predators, while open-and-closed canopies fit the different needs of many bird species. Standing dead wood provides cavities for nesting and attracts insects that birds feed on, while gaps in the trees mimic natural disturbances, allowing seedlings to sprout.

“It's OK to cut some trees,” said Andrew Shultz, landowner outreach forester for the Maine Forest Service. He explained that selective thinning, which can be a single tree or a half acre, helps biodiversity and enhances wildlife habitat. “A lot of the attributes that birds like, other critters like, too.”

While the total area of forested land in Maine is nearly the same as it was in pre-colonial times, it has lost much of its complexity. In the 19th century, towering white pines were prized as ship masts, while beeches and oaks became barrels. The 20th century brought industrial logging, with the state once home to the world’s largest paper mill.

Maine’s forests today are a remix of human activity, invasive plants and insects, a warming climate, and tree species decimated by beech bark and other diseases. Abandoned farms have returned to forest, although the trees are smaller, younger, and more homogenous in age and size.

“Forests have returned throughout New England, but Maine is much less developed,” said Andrew Barton, University of Maine-Farmington biologist and author of The Changing Nature of the Maine Woods. He explained that the state’s forests are less fragmented than elsewhere. “For species that need unfragmented, intact forests, Maine is incredibly important as a baby bird factory.”

Barton, the owner of a 100-acre woodlot, is one of 86,000 small-family landowners in the state. He understands the value of small clearings. He wants to see bigger trees and a more complex structure on his land, and to harvest trees “in a way to promote wildlife.”

In the most recent U.S. Forest Service National Woodland Owner Survey for Maine, family landowners cited beauty, wildlife, and nature as their top three reasons for owning. Many have been on their land for more than a quarter century.

Maine Audubon has been conducting workshops statewide for these landowners and produced a free landowner guide. A more detailed 130-page forestry guidebook is available for download, with a print edition distributed at the workshops and available for purchase. A guidebook for loggers is in the works.

About a quarter of Maine’s licensed foresters have taken workshops so far. Shultz has also sent the Maine Forest Service district foresters to the workshops.

But Maine is not the only state where the forests are going to the birds.

The inspiration for Maine’s program came from Vermont, which launched its Foresters for the Birds project in 2008, a partnership of Audubon Vermont and the Vermont Department of Forests, Parks, and Recreation. Steve Hagenbuch, a conservation biologist who has been with Audubon Vermont for 20 years, said that while species recovery takes time, annual bird inventories in their demonstration forests show a “positive response” by the birds.

Hagenbuch also described the response of state landowners and foresters as “outstanding.” When asked how Vermont’s program achieved success, he explained, “You really have to have all the stakeholders at the table.” Just as important: “I strongly advocate for making a good, strong scientific bird conservation rationale behind what you're trying to do.”

Barton told me that he sees programs like those in Maine as scientifically sound. “They really have cutting-edge research that it’s all based on.”

The Forest Stewards Guild is now working to adapt and bring bird-centered forest programs to Rhode Island and North Carolina, said Amanda Mahaffey, the Northeast region director. They’re also looking to the Great Lakes states and Oregon.

It can’t come too soon for birds like the rusty blackbird, which has declined by 85 percent since the 1970s, or the Canada warbler, which depends on shady undergrowth. Declining at a rate of 3 to 4 percent a year, the rusty blackbird is what Gallo calls the “poster bird” for crashing populations.

Eastern forests have already lost the passenger pigeon and Carolina parakeet to extinction. The rare Bachman’s warbler is federally endangered, and there have been no definitive sightings of the ivory-billed woodpecker despite a five-year search by the Cornell Lab of Ornithology. According to the 2009 USGS State of the Birds report, about one-third of all forest-breeding species nationally have declined since 1968.

Based on the ospreys circling overhead and the wood thrushes foraging on the forest floor, Sewall Woods seems well along as a healthy woodland for birds. The morning fog is lifting as we complete our walk, having stopped at eight points along the trail that will be marked with interpretive signs. Gallo says the ultimate goal is for more private landowners to manage more acres for bird habitat.

Already seeing success in “influencing the culture of how foresters and loggers and landowners think about the woods,” Mahaffey calls birds “the perfect spokesperson” for the forest.

The Magazine of The Sierra Club

The Magazine of The Sierra Club