Bottle Shock

How can campus sustainability crusaders navigate polluting corporate contracts?

Fondly or, depending who you ask, infamously referred to as “ZooMass Slamherst,” or “the Zoo,” the University of Massachusetts Amherst has a long-held reputation as a party school—but one with a mean green streak. UMass’s 23,000+ undergraduates compost more than 1,500 tons of food each year. The university offers a bike-share program, boasts more than 15,000 solar panels, and reduced its total greenhouse gas emissions by 27 percent from 2002 to 2016. Last year, it recycled 489 tons of single-stream products and 506 tons of cardboard. By 2050, UMass hopes to claim carbon neutrality.

For such a large university, this is an impressive record. But it’s marred by the scourge of an all-too-common source of campus pollution: its own, branded plastic water bottle. Handed out at orientation and sporting events, and sold all over UMass Amherst, discarded bottles are a familiar sight on the picturesque New England campus.

Single-use plastic water bottles have a lifespan of roughly 500 years, meaning that every ounce of plastic manufactured since the material was created still exists somewhere today. On top of that, the Pacific Institute in 2007 found that it took 17 million barrels of oil to produce enough plastic to keep pace with Americans’ bottled water consumption in 2006. A 2015 Science article estimated that more than 8 million tons of plastic waste annually enter the oceans, where, by 2050, plastic debris is expected to outweigh fish.

“Since we're a university that says that it’s very sustainable, we thought that it was kind of ridiculous that we had our own brand of plastic water bottles,” says UMass student Timmy Sullivan. A Massachusetts native and political science major, Sullivan is the undersecretary of sustainability within the university’s Student Government Association.

“There’s a lot of cognitive dissonance,” adds SGA secretary of sustainability and senior Ainsley Brosnan-Smith. “A lot of students say they know it's bad, but it's there and it's accessible, and it's a dollar, or it's handed out for free.” Outside this year’s Founders Day barbeque, Brosnan-Smith set up camp next to where the water bottles were being distributed and offered an alternative: compostable cups. Still, many opted for the water bottles—even some who had reusable bottles stuffed into their backpacks. “There are a lot of students who are trying and a lot who want to see the plastic go away,” she says, “but at the same time there are a lot of students who really just don't care.”

The university’s instincts for self-promotion, however, aren’t entirely to blame; the issue largely comes down to UMass Amherst’s binding corporate contract with beverage giant Coca-Cola.

As a whole, the beverage industry is largely controlled by the factions of Coca-Cola Co. and PepsiCo Inc., which is why soda-swilling patrons at most restaurants, amusement parks, and sports complexes have no choice between the two: it’s either Diet Coke or Diet Pepsi, Sprite or Mountain Dew. As it turns out, college and university campuses run along the same divide. Boston University? Coca-Cola. University of California Davis? Pepsi. UMass Amherst? Coca-Cola. Students like Brosnan-Smith and Sullivan are involved in an initiative to ban plastic water bottles on campus, but due to UMass’s contract with Coca-Cola, they’re up against a Goliath.

UMass Amherst entered into its current, five-year contract with Coke in 2014. Campus officials say that in 2019, the university will likely take Coke up on an opportunity to extend for another five years. Over the course of the 10-year “sponsorship,” as Coca-Cola describes it, Coke will pay the university $6 million. Each year, $60,000 must be spent on “mutually-agreed merchandising items” (hence, the ubiquitous branded water bottles), and in exchange, the “Bottler” (Coca-Cola Refreshments USA, Inc.) donates up to $5,000 annually for student and faculty special events. Coca-Cola also has rights to UMass’s logos, which can be used on a royalty-free basis “for the purposes of marketing, advertising or promoting” both Coke and the university.

Coca-Cola has “exclusive beverage availability rights on the entire campus at all times” during the contract. The university must make Coca-Cola beverages available for sale campus-wide, in fountain dispensers, coolers, and vending machines. The beverage giant also owns a certain percentage of shelf space in campus retail areas. Which means that if students were to effect a ban of UMass-branded water bottles and remove the products from campus refrigerators, that would only open up more shelf space that’s contractually obligated to Coke. As Brosnan-Smith explains, this provides the opportunity to sell more unhealthy alternatives and high-sugar drinks.

“It really just ties their hands,” she says. “It's hard because Coca-Cola gives the campus a lot of money—they give a lot to athletics and scholarships and that's why UMass likes them. So in terms of moving forward with sustainability and banning the bottle, I don't see how it would be likely, because of the contract.”

Such contracts with schools provide millions for beverage giants and hundreds of thousands of dollars in sponsorship and campus scholarships—and they’re as common as they are are lucrative. Out of Sierra magazine’s Top 10 2016 Cool Schools, two have a contract with Pepsi, four are with Coca-Cola, and four have no contract. An article in CrossFit Journal reported earlier this summer that out of America’s 3,000-plus college and universities, less than .09 percent are known to have broken ties with “Big Soda.”

One among them is Sierra’s No. 1 Cool School of 2016 and 2017—College of the Atlantic (COA) in Maine, which in 2013 severed ties with corporate beverage companies after students petitioned to purge a campus Coca-Cola vending machine, as well as an Odwalla (owned by Coke) cooler and a Nestlé juice machine. About a decade prior to that decision, students dragged a Coke vending machine out to Maine Route 3, then affixed a paper thumb to the machine to make it appear as if it were hitching a ride.

“The student population tends to be an activist population, and they tend to be vocal about what they do and do not like,” says Sarah Luke, dean of student life at COA. “We don’t prohibit these [beverages]; it’s just not something we institutionally support by providing money or resources towards those food products or corporations.”

Although COA is a school of fewer than 400 students, it’s set a precedent for other institutions.

Still, Brosnan-Smith says, Coca-Cola gives UMass Amherst too much money for school officials to say no. “We have so many of those [UMass] plastic bottles everywhere that we're increasing plastic just to compete with Coke, which produces a lot of plastic itself,” she adds. “The university is thinking more from a business than a student perspective. But more students don’t want, than want, the plastic bottles, and isn't the campus supposed to be for students? A place where we effect change and express ourselves freely? Not a business model for the administration to make money from?”

When asked about the relationship, a UMass Amherst official cited Coke’s sustainability as a factor in the university’s decision to award the five-year contract.

“Coke identified a number of ways it was addressing recycling and sustainability, including its Reduce, Recover and Reuse program,” says Daniel Fitzgibbons, the university’s associate director for news and media relations. He also notes that Coca-Cola has sponsored campaigns to increase awareness on sustainability and encourage students to recycle, that its vending machines use HFC-free refrigerants, that hybrid electric trucks facilitate deliveries, and that Coke provides $5,000 annually to UMass Amherst for recycling and sustainability initiatives.

UMass Amherst’s sustainability community, however, isn’t buying in. Despite its green intentions, Coke, which sells nearly 100 billion bottles a year, only recycled seven percent of its sourced materials in 2015. Although UMass’s contract is in place until at least 2019, the SGA is working to combat the amount of plastic on campus by passing motions to increase recycling rates and reduce trash. But more often than not, students say, bottles are still simply thrown in the trash, a discouraging fact that aligns with nationwide trends: A 2013 American Chemistry Council report found that Americans only recycle 31 percent of their plastic bottles.

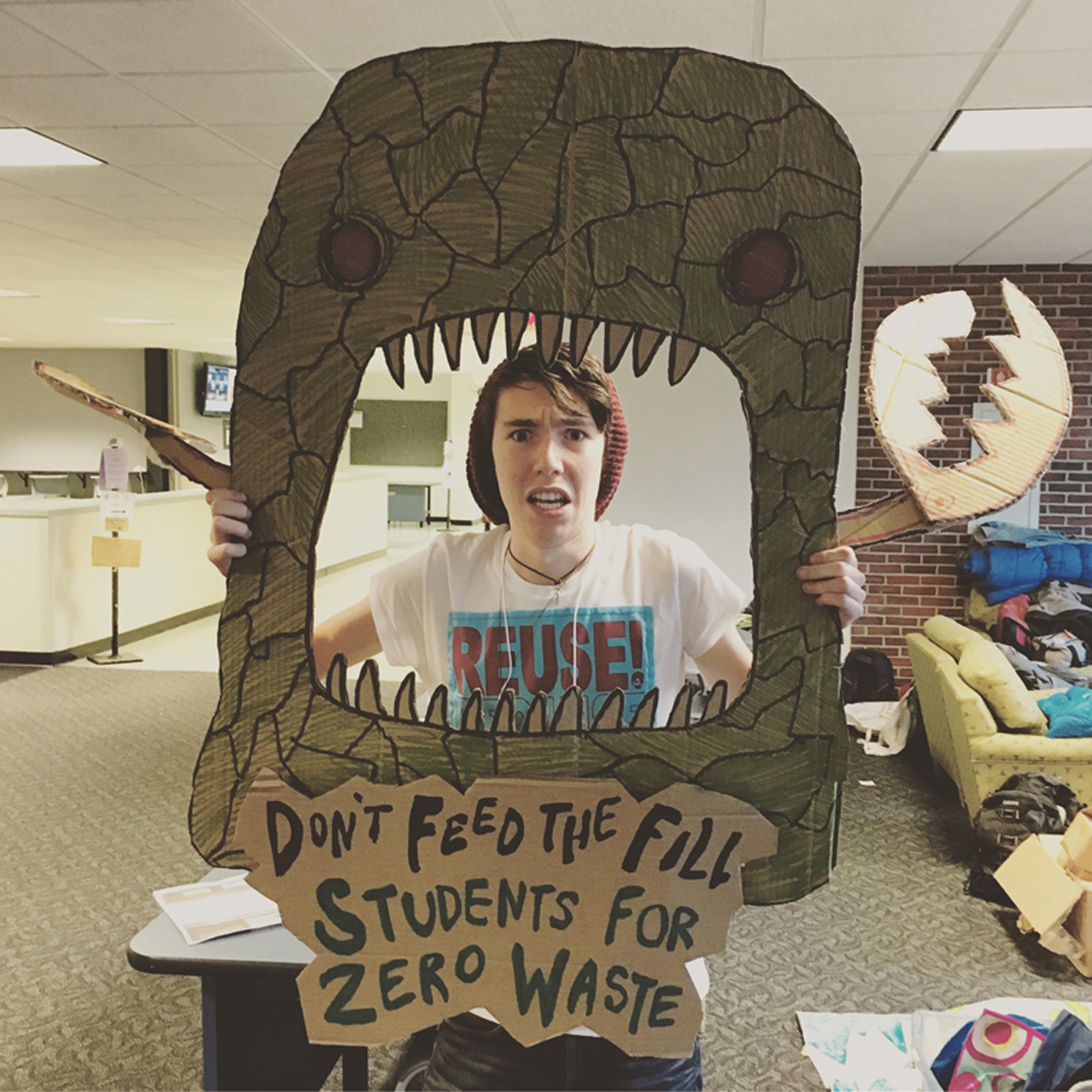

Photo courtesy of Timmy Sullivan

“We're examining a few avenues, working on campus within the means of the contract, to get students to consume less plastic,” says Sullivan.” But educational campaigns only go so far. So we're trying to work with university administration to find other ways within the contract to reduce plastic consumption. If that means having more water dispensers around campus, or using the glass Coke bottles, that would be a compromise I'd be willing to make.”

One possible way to circumvent the contract would be for the municipality of Amherst, which banned plastic bags last winter, to prohibit single-use plastic bottles—which has indeed been a topic of discussion among city council members. Under the terms of its contract, Coca-Cola has to abide by all municipal laws. Of course, students also could push for the university not to re-sign the beverage company once the contract is up for discussion.

“We claim to be a campus that's really sustainable, but we have heavy ties to one of the biggest corporations that contributes to plastic bottle pollution,” Sullivan says, echoing Brosnan-Smith’s frustrations.

“Corporations like Coke aren't going to change their practices on their own. It's going to take a lot of push from consumers to make these changes, and I think universities are really positioned to put a lot of pressure on corporations,” Sullivan says. “We live on a finite planet, but we continue to consume as though we have an infinite amount of resources. So until we switch to a culture that institutionalizes zero-waste practices and makes reusables part of daily life, we're not going to solve the climate crisis.”

The Magazine of The Sierra Club

The Magazine of The Sierra Club