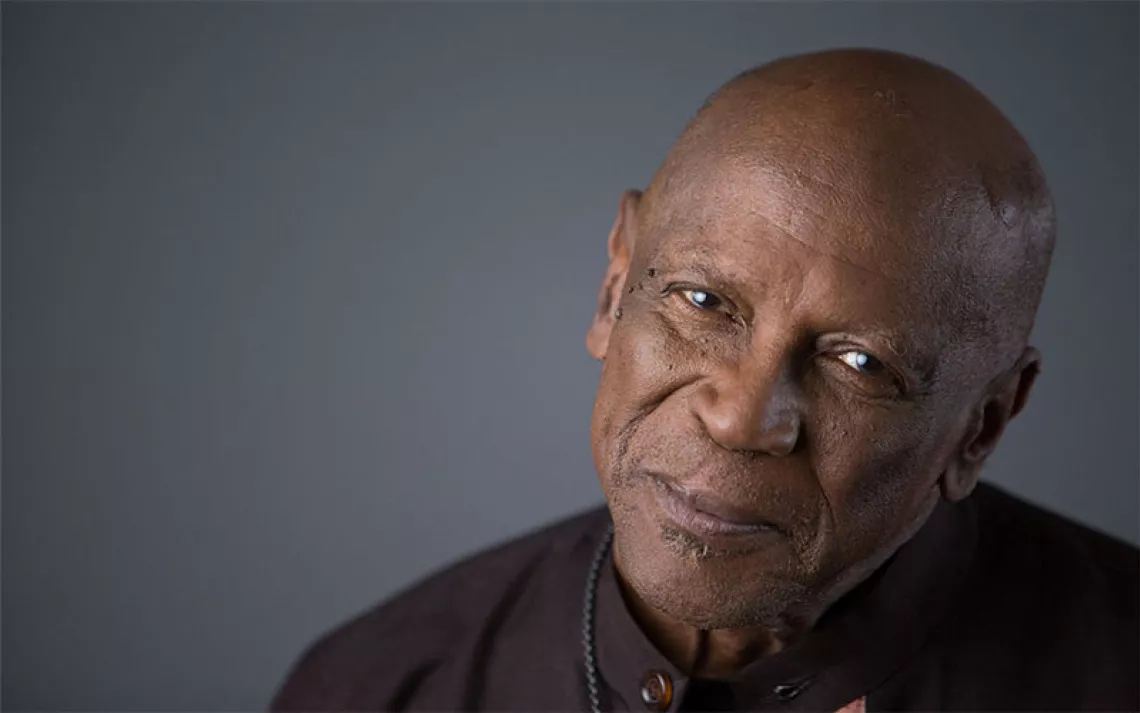

Community Activist Anthony Torres Receives Youth Brower Award

It might sound radical, but this youth organizer wants a world that works for us all

Photo by Storyline Media, courtesy of Earth Island Institute

Anthony Torres wants a more just world. To get there, he believes in drawing people together from different movements, something he learned to do first by coming to terms with his own plural identities.

Torres is the son of an immigrant from Nicaragua and a white, United States–born mother who made her way from the working class to a comfortable middle class life. He’s also an environmentalist who grew up near Long Island’s barrier beaches and rising sea levels. In his most current role, he’s the campaign representative for the Sierra Club’s Responsible Trade Program.

On Tuesday evening, the 23-year-old was one of seven recipients of the Brower Youth Award, which annually honors young leaders in the environmental movement from across the United States.

In high school, Torres worked as a wildlife steward in the town of Babylon on Long Island. He and his fellow stewards combed the same 10-mile stretch of beach each day, surveying for endangered species, testing for contaminants, and checking up on a clam restoration project.

“We were pretty much the only folks out there except for the rare marine patrol,” Torres says. “We were the protectors of that land.”

Then in 2012, shortly after Torres left for college, Superstorm Sandy struck. Torres returned to the area during his winter and summer breaks to help with restoration efforts and was shocked by how much the coastline had eroded. Even more striking to Torres was the inequity of the recovery efforts. “Those who had beachfront property were given all the resources they needed to rebuild, whereas communities of color and low-income communities in Brooklyn and Queens did not get the same help. It took years for them to be able to recover.”

It was a formative experience. “We were all left reeling and paying for this disaster,” Torres says, “while the fossil fuel CEOs and politicians who continue to perpetuate these disasters were unscathed. That’s a pattern that set me off into this work.”

While still in college, he spent a semester in Ecuador as part of a program called Rehearsing Change. Using theater and storytelling to promote social justice, the group worked with a hip hop collective in Quito, and then with indigenous communities in the Amazon that were opposing oil extraction. It was there that Torres learned what it means to be an ally to a frontline community.

Since then, Torres has been an active movement builder in youth-led organizations like All of Us and the Sunrise Movement, which strive for climate justice and more democratic governance. He has staged what he calls strategic interventions, such as a dance party outside of Ivanka Trump’s house and a vigil for Hurricane Harvey victims outside Rex Tillerson’s residence. He’s held sit-ins in the offices of Congress members, including one in Delaware senator Tom Carper’s office, shortly after which Senator Carper came out against the Keystone XL pipeline.

He also got involved in the fight against the Trans Pacific Partnership, and after graduating, he was hired to work on the Sierra Club’s Responsible Trade team, just at the peak of the effort to defeat that trade deal.

Climate justice, economic parity, immigrant rights, and labor protections—for Torres, trade is the nexus of all of these issues. He sees the Sierra Club as one of the few national environmental organizations working to advance a plan for trade that focuses on healthy, thriving communities, good union jobs, and action on climate change.

“We have to expand our view of what it means to fight for our environment,” he says. “The work the trade team and I do has really been about articulating a vision of environmentalism that is centered on people, human rights, and the needs of communities.”

A big part of the job is educating others about the impacts of trade deals like NAFTA and what Torres calls Trump’s NAFTA 2.0—the even more corporation-friendly pact that could replace NAFTA if the Trump administration follows through on its promises to scrap the original deal. “Trade policy has been crafted in a way that gives corporations special privileges above our environmental and public health regulations, or any local, state, or federal protections,” Torres explains. For instance, under a provision in NAFTA, a U.S. oil and gas company called Lone Pine Resources is suing Quebec to undo the province’s moratorium on fracking under the St. Lawrence River. “Workers, the environment, communities of color, and immigrants have all been on the receiving end of these bad policies.”

Torres says getting these groups and others to recognize how much they have in common is essential for defeating corporate trade deals.

“A lot of the work I do is about trying to weave together a common vision, and a common agenda, that slingshots our movements forward,” he says, “and provides the political power we’ll need to really change the world.”

The Magazine of The Sierra Club

The Magazine of The Sierra Club