The Colonels

In praise of the ordinary night heron

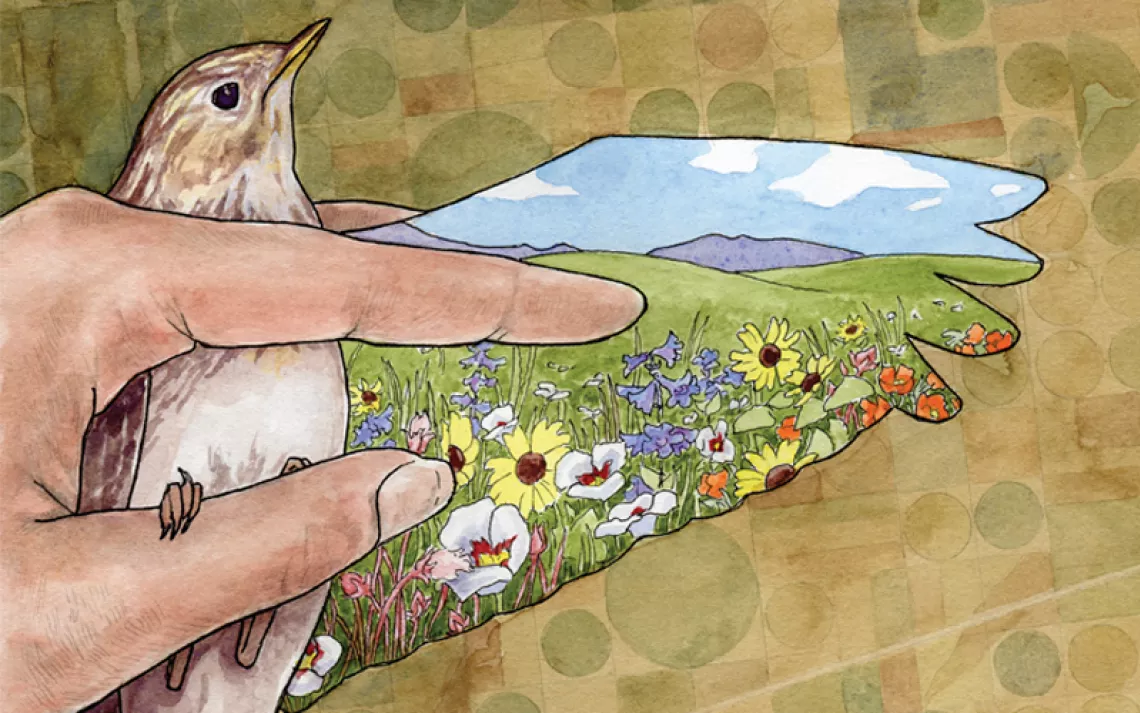

Photo by Jenny Odell

The first time I saw a black-crowned night heron, it was late one night on the docks of Alameda, California. My first thought was, “there’s something wrong with that seagull.” As I got closer, the being in question revealed itself to be a football-shaped bird, sitting perfectly still on the edge of the dock, its formidable beak pointed down at the water. There was something compressed and grumpy about it.

A year later, I moved to Oakland and began to notice a small group of similar birds hanging out on the fire escape of the Grand Lake Theatre, a historic movie palace near Lake Merritt. They were also partial to the patio umbrellas of the KFC around the corner. Given their location, my boyfriend and I nicknamed them “the colonels.”

They were almost always there during the day and sometimes at night. My phone filled up with night heron photos, many of which could easily be mistaken as the same photo. At some point I realized that I had started modifying my walking route to pass by the colonels, sometimes even waving and saying hello as if I had run into an old friend. The nighttime security guard on the corner where the colonels hang out started giving me funny looks.

But I found myself at a loss to truly account for my love of night herons. They are neither rare, nor terribly endangered. They are not classically cute, like a goldfinch, or obviously majestic, like a great blue heron. But every time I saw a night heron, no matter what, I broke into a stupid grin.

Part of it had to do with the special qualities—or the personality, if you’ll have it—of night herons. The most obvious was their stubborn stillness. Night herons hunt at night, so a heron during the day might try to find a sunny place (like the roof of a KFC) for a nap. I’ve often passed by one of them sleeping, only to have it slowly open one of its laser-red eyes and peer down at me without moving its head.

But night herons are just as still when they’re hunting. A writer for Ocean Wild Things notes that this quality is actually one of the easiest ways to identify night herons: “While most other birds are busy preening, hunting, or flying, black-crowned night herons are completely immobile.” They bring to mind advice that a friend recently told me, from the philosopher Krishnamurti: “Remain completely alert, and make no effort.”

I felt comforted by their consistency. All around me in Oakland, new condos sprouted, warehouse collectives dispersed, and the Sears building downtown disappeared into a plastic cocoon as it was renovated in anticipation of its new owner: Uber.

In the shifting sands of the internet, where I spent far too much time, the landscape changed even faster.

With pigeons, seagulls, and crows swirling around overhead, the unmoving night herons have come to seem to me like the Bartlebys of the bird world (Bartlebirds, I call them). Soon after noticing the colonels, I started writing an essay called “How to Do Nothing.”

A large night heron colony used to live in the ficus trees on 12th and Howard. Recently the trees were removed for a housing development, and the developer hired biologists to relocate them to different trees around Lake Merritt. The biologists used decoy night herons and recorded bird calls to encourage the night herons to move to new nesting sites that they had prepared for them. The success of this initiative remains to be seen—the project is only three months in, and relocating the birds could take years. Sarah Phelan, covering the move in the East Bay Express, asked with good reason, “Can you get night herons, which spend their days hunching motionless, to move when and where you want?”

Night herons stay put not only individually but also collectively. One colony has summered in Washington, D.C., at the National Zoo, for more than a century, and night herons can live up to 20 years. The herons have existed in Oakland since before Oakland was a city. Like crows, part of their success has been adapting to the human environments built up around them. They’ll readily eat trash, do not seem to mind traffic, and will nonchalantly stand in the middle of a sidewalk downtown. Resolute in both space and time, night herons are the stocky ghosts of marshes past.

That’s one reason to love night herons, but there’s something more. For lack of a better term, I would argue that there is also a secret weirdness about them.

People often describe night herons as having “no neck.” In fact, they have long necks just like other herons, but they keep them folded up and hidden away in their feathers. I didn’t discover this until last year, when I watched a night heron on the sidewalk in front of the KFC slowly and surreally stretch its neck out, perhaps to look at something particularly interesting across the street. Then, just like that, it returned to a compact oblong as if nothing had happened.

Night herons are also unexpectedly graceful in flight. Their wing beats are recognizable from afar—full, round, and leisurely, and they trail their legs lengthily behind them. I’ve watched them fly over my neighborhood at dusk as well as from the Stanford campus, where I sometimes see them heading toward the bay after class. At that hour, by some magic, their blue-gray wings seem to match the color of the sky. It’s a sight that Arthur Cleveland Bent captured perfectly in his 1927 Life Histories of North American Shorebirds:

How often, in the gathering dusk of evening, have we heard its loud, choking squawk and, looking up, have seen its stocky form, dimly outlined against the gray sky and propelled by steady wing beats, as it wings its way high in the air toward its evening feeding place in some distant pond or marsh!

Their evening flights are one of the rare times I’ve heard a sound from a night heron—a dinosaurish not-quite-quack that is often spelled “quok.” In fact, the birds are named some variation of this sound by languages other than our own: kwak in Dutch and West Frisian, waqwa in Quechua, vạc in Vietnamese, kvakoš nočn in Czech, and quark on the Falkland Islands. Night herons hunt in the evening to avoid competition with other shorebird species. Unable to claim space for themselves, they territorialize time instead.

Recently, I stumbled upon the night heron El Dorado. I was in the Mountain View Cemetery an hour before sunset, on my way to a hill behind the cemetery where I like to sit, motionless and night-heron-like. There are a couple of ponds in the cemetery where you can reliably see a few shorebirds and maybe even a turtle. This time of year, the water in the ponds is high, and the leafless trees stood half-submerged in the duckweed.

It was there, between the tangled branches and in the reedy edges of the pond, that I saw them: at least 18 night herons—not only adults, but also the ruddy, speckled juveniles. I realized that all of the times I’d seen night herons flying over my neighborhood, they’d been headed in this direction. It was possible that the colonels were somewhere among them.

When I tried to take a photo, the neon color of the duckweed in the setting sun threw off the exposure on my phone, so all I could capture were ambiguous orbs amidst the green. A few herons were flying around overhead, quokking energetically, something I had never witnessed. I was put in mind of all the other parts of the night herons’ lives that I hadn’t seen: the furtive spoils of their hunts, the shape of their nests, the sound of their mating dances (during which the male reportedly stretches out that secret neck and bobs his head, then grabs a branch nearby and shakes it, known as a “twig shake”). With all my watching, I have still never caught a night heron with a fish in its mouth.

I was reminded of earlier this spring, when the dry and seemingly barren hill behind the cemetery exploded with flowering vetches, rose clover, lupines, and California bee plant—expressions of everything in the ground that I didn’t know was there.

In Konjaku Gazu Zoku Hyakki, an 18th-century bestiary of the supernatural demons and spirits (yōkai) of Japan, there’s a description of a phenomenon called Aosaginohi, or “blue heron fire.” According to the associated folklore, black-crowned night herons sometimes begin to glow in old age. Transforming into yōkai, they fuse their feathers into scales that give off a bluish-white glow, their breath releasing a golden fireball that eventually disperses into the evening.

I had this in mind as I left the cemetery in the gathering dark. Just as easily as I knew where to find the colonels the next day, it wasn’t hard to imagine another thing that I had never seen: late at night after the cemetery closed, a ring of glowing birds around the pond, waiting for fish.

The Magazine of The Sierra Club

The Magazine of The Sierra Club