Colombian Elections Could Move Environmentalism to Center Stage

Afro-Colombian land defender Francia Márquez could become the next vice president

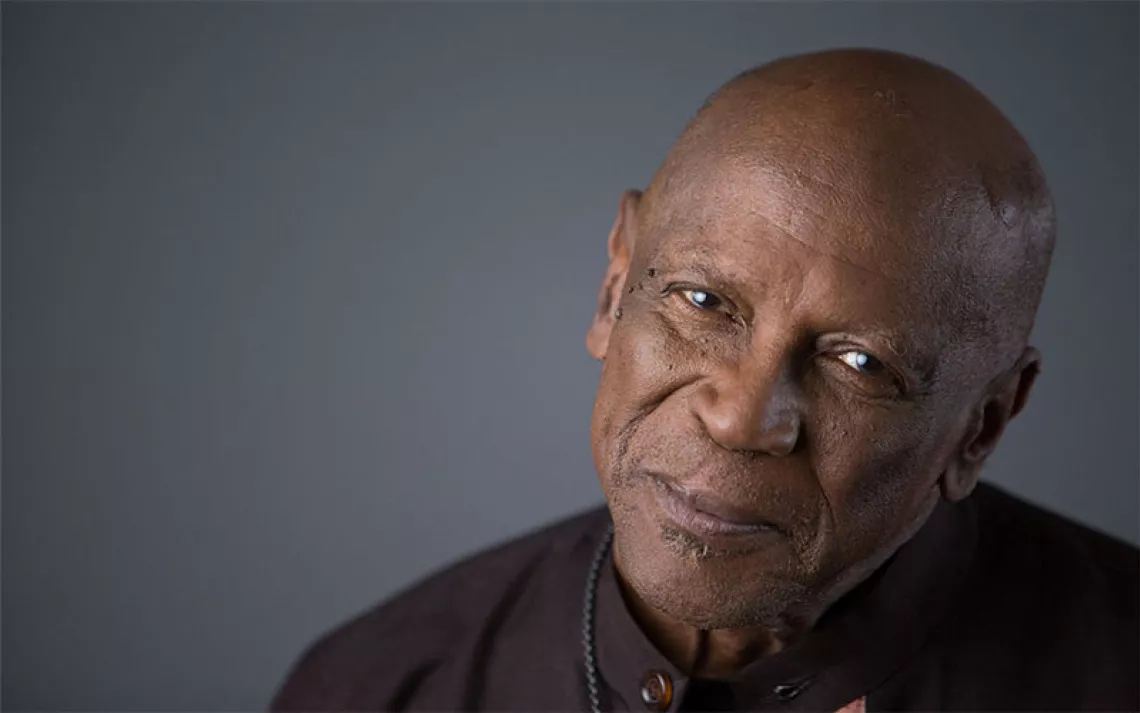

Photo courtesy of Daniela Diaz

Update: On June 19 Petro Gustavo was elected Colombia's first left-wing president along with Francia Márquez as the country's next vice president.

Dozens of brilliantly colored turbans shone in Plaza de Bolívar, the seat of government in Bogotá. The more than 70 Afro-Colombian women who wore them had marched hundreds of miles across central Colombia to demand an audience with a government that had ignored their community for decades. The woman who led them across the Andean country, Francia Márquez, was an environmental activist, a young single mother, and a former domestic servant who had put herself through law school.

Her voice carried above the sound of the crowd as she demanded protection for her homeland and protection for its people.

On that day in 2014, Francia Márquez was unknown to the wider Colombian public, but the women activists from Cauca would soon captivate the public imagination in a standoff with the national government. In what came to be called the “March of the Turbans,” a group of social activists from a small town of La Toma—which had been suffering extreme environmental damage as well as outbreaks of violence due to both illegal and state-sanctioned mining—demanded that the government withdraw mining titles granted without the consent of the people who lived there. The activists occupied the historic square where Congress and the Constitutional Court reside. The women of Cauca eventually sat down with the Ministry of the Interior and the government ceded to their demands.

Four years later, in 2018, Márquez won the Goldman Prize for environmental activism for her decades of environmental activism in Cauca. She survived an attack by would-be assassins in Santander de Quilichao, Cauca, in 2019, as men with grenades and rifles attacked a conference of activists who worked in the region. Colombia is the most dangerous country in the world for human rights activists and land defenders: 138 were killed in 2021.

Now, Márquez is running to be Colombia’s next vice president in an election that could be historic if she and her running mate, leftist front-runner Petro Gustavo, win on Sunday.

“Environmentalism is not only about caring for nature,” Márquez told Sierra in a written statement, “it is also about caring for the community and caring for culture. I did not become an environmentalist as a personal choice. Society has no choice but to become environmentalistic if we hope to survive.”

Gustavo tapped Márquez to be his running mate in March. The move represents a sharp departure from traditional politics in Colombia, which have historically been dominated by white men from wealthy central regions of the country. Marquez’s appointment gave a considerable boost to Gustavo’s campaign. In last month's presidential primaries she received the third highest vote tally of any candidate in the field, and she brings with her a coalition of grassroots activists and social organizations in rural regions that have long distrusted the “establishment politics” that Gustavo represents.

But more important for fellow activists, she also represents a rare moment when environmental issues, long ignored by the right-wing administrations that have held power in Colombia for decades, have taken center stage in a political campaign.

One of Petro’s campaign planks is to rein in a hydrocarbon-dependent economy, which currently represents nearly a third of the government's operating budget, and replace it with clean energy. Márquez has made her career shining a light on the social and economic damage caused by mining, which has long had a direct negative impact not just on ecosystems but also on human rights in conflict regions.

“To be an activist in Cauca is to live a life under threat,” Clemencia Carabali, an environmental activist from Cauca, told Sierra. “Armed groups have almost total control over the region. And when the interests of these groups are threatened, when social leaders raise their voices, they silence us.”

Photo courtesy of Marilyn Machado

“What Francia represents for those of us who live and work in this region, more than just an inspirational symbol, is a chance to spotlight the social, economic, and environmental damage that extraction industries cause in our communities,” she continued. “It is an issue that the current government would rather ignore.”

Illegal mining has been even more devastating to Cauca than its legal counterpart. Eighty percent of all gold mined annually in Colombia is produced illegally, and is a primary contributor to deforestation in the Amazon rainforests as well as contamination of river tributaries and water tables. Mining involves the use of chemicals dangerous to human life and ecosystems as well as heavy metals such as mercury and lead.

“What I would do [as vice president] is encourage a change in values,” said Márquez. She would “encourage society to learn and to live harmoniously. For that to happen we need more seeds, better agricultural practices, more caretaking for forests and for the people that inhabit them. [We need] better caretaking for the waters and the life they harbor."

Márquez and Gustavo have proposed a plan to curtail deforestation, invest in clean energy, and begin weaning Colombia away from a hydrocarbon-extraction-based economy, which currently accounts for nearly a third of the government's operational budget as well as the country’s principal export. Márquez advocates for investment in agriculture and tourism as well, especially in conflict regions where employment opportunities are lacking and where neglect across multiple administrations has led to a rise in gender-based violence, economic destruction, and cycles of poverty and violence.

“We are one of the most biodiverse countries in the world,” she recently said in a live interview with Colombian media. “And there are sustainable ways to stimulate economic growth using this natural wealth in a responsible manner.”

“Francia has been part of our movement for decades,” said Cha Dorina Hernandez, the first Black congresswoman from San Basilio de Palenque, a historic district known as the first free town in the Americas. “I met her when she was 15 while working on a campaign to preserve rivers in the Pacific.” For Hernandez, the appointment of a Black women to potentially fill the second highest office in the country is a victory in itself. “She is inspiring an entire generation of new leaders,” she told Sierra. “Her victories are our victories.”

Marilyn Machado, a sociologist and human rights activist in the north of Cauca and a longtime colleague of Márquez's, was one of the women present at the March of the Turbans demonstrations. She says no one could be better suited than Márquez to advocate for environmental reform in Colombia. Machado laughed as she recalled their victory in Bogotá. “Most of us were women from the countryside,” she explained to Sierra. “Most had never even been to the capital before. For us it was a strange, unknown place, cold and distant from the struggles we knew.”

“And the negotiations! Imagine the scene,” she continued, still laughing. “At most of the meetings it was me, Francia, and a few others on one side of the table, and an army of lawyers and experts on the other. They did their best to intimidate us. But Francia was never deterred for a moment.”

“In Cauca we have a saying,” she said. “The river is both father and mother. It is a great example of what nature means to us—something we have a very spiritual respect and love for. It is our origin, our family. We were born from it. For us, this connection is deeply cultural. That is the world Francia comes from. And she isn’t going to let an army of politicians prevent her from defending it.”

“Everything is linked,” Márquez told Sierra. “Without justice there is no peace. Without peace there is no tranquility or respect. We must be prepared as a society to face the incredible global challenges posed by the climate crisis. In order for defenders of nature to face fewer risks, society itself must become a defender of nature.”

The Magazine of The Sierra Club

The Magazine of The Sierra Club