The Push to Save the Coho at Dry Creek

The Warm Springs Dam isn’t coming down anytime soon. Conservationists want to use it to help save salmon.

The land bordering Dry Creek is under a patchwork of private ownership, almost all of which is vineyard. The habitat enhancement project will eventually contain six noncontiguous miles and involve dozens of landowners. This site, recently established on an easement of Ferrari-Carano Vineyards, includes stream diversions, slow-flowing water features, bank stabilization, and native plant restoration, all of which serve as ideal habitat for endangered coho salmon.

Can a dam help restore a critically endangered coho salmon population in Northern California?

That sounds like heresy, but Warm Springs Dam, which impedes Dry Creek to create Lake Sonoma, is a source of cool, clean water. These flows may be an essential component of a broad recovery program the National Marine Fisheries Service (NMFS) mandated in 2008.

Dams have been a central reason that Pacific coast salmon populations have plummeted or vanished during the past century, but the Warm Springs Dam, completed 40 years ago for flood control and water storage, isn’t going to be removed anytime soon. So those tasked with trying to rebuild coho runs, from the US Army Corp of Engineers to local water agencies, are making use of the cool water released by the dam.

Salmon, which typically spend a year in their native streams before swimming to the ocean for two years then returning to spawn, like cool water. Most species become susceptible to disease when temperatures rise above 60°F. A problem in Dry Creek, a 14-mile tributary of the Russian River in Sonoma County’s wine region, can be too much water due to mandatory releases—an ironic counterpoint to streams parched by periodic droughts.

Sudden high flows flush out the creekside oases formed by woody debris where juvenile salmon can shelter and grow. These dam releases, especially in high water years, also wash away gravel that salmon need for spawning.

Dam-release flows “run really fast” and create a “straighter channel,” said Ann DuBay of Sonoma Water, the county agency. “Coho like shallow water. They like ripples. They like complexity. They like places to hide.... It’s challenging for them to thrive when they have that much volume.” The Russian River Biological Opinion (issued in 2008 by NMFS) mandates federal and local agencies to “provide hiding places and refuge in Dry Creek for young coho salmon and steelhead trout.” The opinion requires six miles of habitat be constructed in the 14-mile-long creek.

Eric McDermott, a biologist for Sonoma Water, monitors a viewing window at the Mirabel inflatable dam. Upstream migrating salmon must pass through this observation point, allowing for accurate population counts while the dam and fish ladder are active. In the fall of 2022, when this photo was taken, returns were later and lower than expected. Sonoma Water's annual report described the 2022-23 return as "among the lowest in a decade."

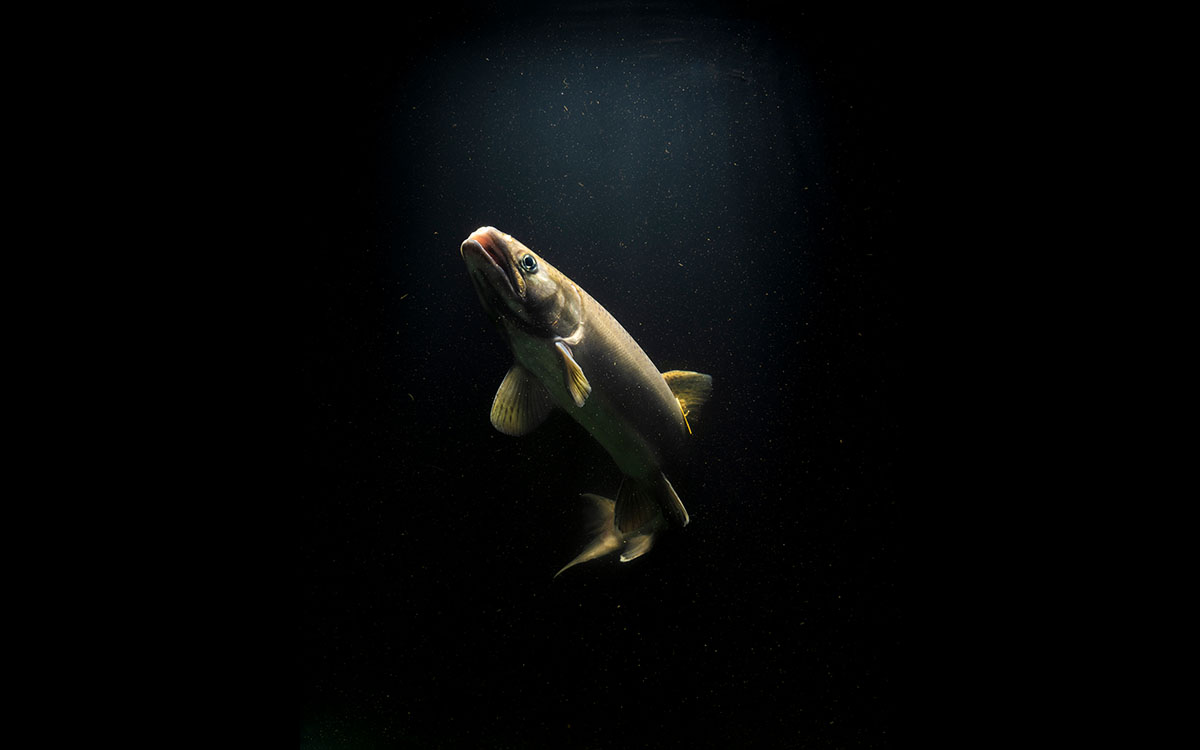

Coho #219 spawned in 2023 as a “jack" (precocial, off-cycle, young male salmon). This natural behavior inadvertently mixes genetics across different salmon runs, increasing genetic diversity in the population as a whole.

Ben White, a biologist for the Army Corps of Engineers, said the project is creating “low-velocity side channels” called “backwater areas” where juvenile fish can thrive. “Even in drought years, Dry Creek (due to the dam) is going to have water flowing,” White said. “So it's always going to be an option for salmon to spawn in, but what it was lacking was juvenile-rearing habitat.” While important and helpful, White said the project can’t address the other causes of salmon decline: logging, gravel mining, overfishing, and excessive water diversions for agriculture, as well as climate change, which is warming water temperatures globally.

The restoration effort, which involves heavy machinery pile-driving long wooden poles into the riverbank, is well underway with more than three miles of the six-mile project completed or nearly finished. “When I first saw the construction, I was shocked. It looked so raw and so unnatural,” DuBay said. “Then to come back over the years, and see how vegetation has grown and how it’s part of the creek environment, is the coolest thing.”

Much of Dry Creek is bordered by wineries. While these landowners were initially concerned about the impact of the project, many are cooperating. Some were “eager to come on board,” DuBay said. Others noticed that high flows were eroding their properties and viewed the project as a way to combat that erosion.

Don Wallace, a proprietor of Dry Creek Vineyards who as a young man helped engineer Warm Springs Dam, played a pivotal role in urging other vintners to support the restoration project. “If you move things in the right way, Mother Nature will come up with a way to kind of patch things together. And that’s what we did. We gave Mother Nature a real toehold here to be able to fix the problems.”

The Dry Creek project caught the eye of commercial photographer Kaare Iverson, who grew up fishing for salmon with his father off Prince Rupert in the northern reaches of British Columbia, Canada. It’s a place where the anadromous fish remain comparatively abundant.

“It really struck me that I wasn’t all that aware of what was happening (to salmon) and that I didn’t feel it as urgently as I did other species’ endangerments and extinctions,” Iverson said. “It was such a stark comparison to the Russian River Watershed where I live now. The contrast made me think about a world without wild salmon, something that’s slowly happening.”

Ken Leister, a fisheries biologist with the US Army Corp of Engineers, loads a male coho salmon into a holding tank of river water spiked with anesthetic. The male, and others like him, will be bred across several females based on a matrix that maximizes genetic diversity within this endangered population.

The sun rises over a recently built side channel on Dry Creek. The vertical stumps that appear as a recently logged streamside are full-length logs that have been pneumatically driven into the ground to stabilize flow-enchancing features. The denuded ground has been stripped of invasive plant species and reseeded with native riparian vegetation. This stretch of water will maintain steady, cool, and slow-flowing water that is ideal for young coho salmon.

Iverson, who now lives with his own family in Sonoma County, hopes to present salmon in a different light. “If people could start to see salmon as a magnificent animal worthy of the same kind of conservation consideration and empathy as megafauna like bison and grizzly bears, then maybe they would start to treat the fish, and the habitat they require, with more reverence,” he said. “I know what this place could be like … and I recognize that it’s going to take a considerable shift in public perception to get it there.”

Around the year 2000, coho in Northern California were on the brink of extirpation, said Sarah Nossman of Sea Grant, a NOAA program (this is different than extinction as extirpation applies to a species’ survival in a region whereas extinction is global). A few adult fish were found in Green Valley and Dutch Bill Creeks. “We were able to save the last of the Russian River genetics for our Russian River coho salmon population,” she said. “It was a last-ditch effort.... Unless we took drastic action and started a brood stock program, we were going to lose these species from the Russian River. So we collected half of the fish that we found and brought them up to the Warm Springs hatchery.”

The progeny, carried in water-filled backpacks, were released into “streams that historically supported coho,” Nossman said, “but not ones that still had runs, so not Green Valley Creek originally and not Dutch Bill, because nobody wanted to mess with any native runs.”

White, of the Army Corps, noted that biologists “actually hike the fish back into the tributaries where they historically lived. We release them at younger life stages with the goal that they'll imprint on those release streams.” The goal is “to trick them into thinking: ‘This is where you were born. This is where you need to come back to as an adult.’” When the program started about 20 years ago, less than a dozen adults were returning to the entire watershed, White said. “That's how close it was to blinking out. We’ve done so much to aid in the decline of the species—now it's time for us to give back and try to do everything we can to preserve and enhance their success. So we're doing a little bit of everything.”

Over the past couple of decades the number of coho returning to four Russian River feeder creeks—Dutch Bill, Willow, Mill, and Green Valley—have ranged from a few dozen to about 300. The 2022-23 number was about 50 returning adult coho, down from more than 200 the year before. White said he and his colleagues have a “very emotional connection to the fish. “We feel a huge sense of ownership.... We raised them from eggs all the way to adulthood. We tag 'em. We take care of 'em. We clean 'em. We try to provide them with the healthiest, cleanest, most low-stress environment possible.”

Yet the decline of wild coho is an indication of a watershed crisis that “needs to be a wake-up call for this whole community,” White said. “We need to do something about it before this species blinks out. Luckily we still have some water; we still have some fish. So in my eyes, we still have hope.”

The Magazine of The Sierra Club

The Magazine of The Sierra Club