Can the Climate Tech Revolution Avoid Leaving Women Behind?

So far, the answer is no, but it’s not too late for change. Here’s what it will take.

AV Bourke, a SolarCorps Construction Fellow at GRID Alternatives. Courtesy GRID Alternatives

This article was originally published by the Fuller Project.

Anna Bautista has heard the stories working in construction: penises and breasts drawn on porta-potty walls, sexist graffiti scrawled on job sites, photo calendars on break room walls featuring scantily clad women. She’s seen women assigned menial tasks such as cleaning, getting lunch, or organizing materials rather than learning new skills of the trade.

This treatment is not limited to old-line construction sites. Bautista, the vice president of construction for Grid Alternatives, the US’s largest nonprofit solar installer, said these problems are also common in the rapidly growing green economy—to the point that she goes to great lengths to present herself as very masculine when on a job site. She’s even worn a wedding ring to a job site—despite not being married—so there would be no questions about what she was doing there. “I was not there to date,” she said.

One of a small group of women working in clean tech, Bautista continues to notice microaggressions such as when partners assume a male colleague is the boss of the job and shake his hand before hers. Or when someone refers to her as “mister” in emails.

“It can feel like death by a thousand cuts,” she said.

Her experiences illustrate a difficult truth for Joe Biden, who has framed clean energy as a win-win for the US economy and environment. “When I think of climate, I think of jobs,” the president told reporters in Palo Alto, California, in June, referring to $370 billion in clean energy funding in the Inflation Reduction Act, which he called the “most significant climate investment law ever anywhere in the history of the world.”

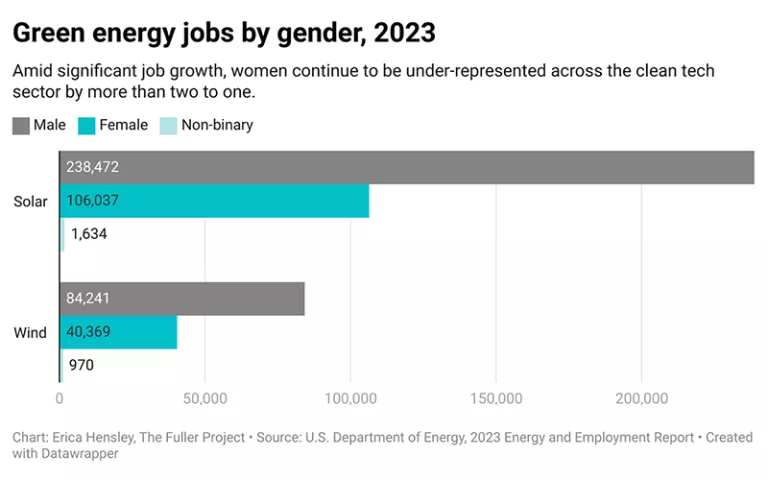

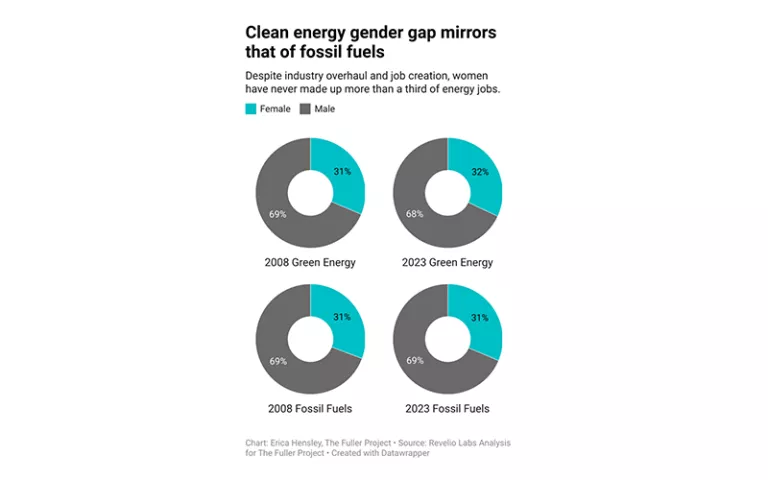

A new analysis of data by the Fuller Project in collaboration with Revelio Labs, a company that uses artificial intelligence to analyze employment data, found that people who hold clean energy jobs in sectors such as solar and wind tend to be overwhelmingly male.

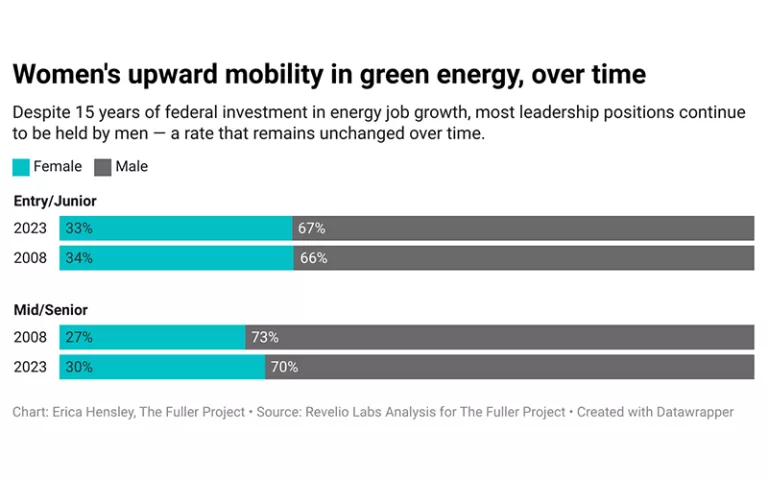

Women compose just 31 percent of workers in green energy, the analysis found, a level largely unchanged since Barack Obama promised to create 5 million green jobs in 2008. The analysis found women are underrepresented at both junior and senior levels of alternative energy companies, mirroring the lack of representation of women in fossil fuel companies.

Revelio reached these conclusions by collecting data from millions of online public profiles, résumés, job postings, sentiment reviews, and layoff notices, analyzing them using proprietary algorithms.

The Inflation Reduction Act (IRA) and the Bipartisan Infrastructure Law (BIL), both signed during Biden’s first two years in office, do require applicants for federal grants and loan guarantees to present community benefits plans, which spell out the efforts grantees will make to promote diversity and accessibility. But there are no required targets. The only goal for women’s inclusion in energy projects is a 45-year-old executive order that recommends, but does not require, that 6.9 percent of work hours be completed by women on federally funded construction projects.

“We have quite a gap to close,” said Amanda Finney, the deputy director of public affairs for the US Department of Energy.

Finney told the Fuller Project that the Biden administration was aware of the gender gap and is looking to lead by example in closing it. The department was the largest funder of clean energy technology in the country, she said, and was screening applicants based on “specific commitments to recruiting and reducing barriers for underrepresented workers, including women.” The community benefits plans required by the IRA and BIL account for 20 percent of the score the agency uses to determine which projects get funded, she said.

Advocates have been warning about the dearth of women employed in the green sector for years. In 2010, after Obama promised a green jobs revolution, researchers at the Urban Institute noted that “the projected growth of green jobs is concentrated in overwhelmingly male-dominated industries and occupations," such as natural resources, construction, and maintenance. Two years earlier, the feminist author Linda Hirshman noted in a New York Times op-ed that “it turns out that green jobs are almost entirely male.”

The solar industry is likewise conscious of the disparities. A report from Solar Industry International, a trade group, notes that “women of color in the solar industry report that they often have to prove their competence, and they face challenges connecting with those in charge of hiring decisions.” The group says it offers specialized training and scholarships to women designed to close the gap.

At the nation’s largest solar tech company, NextEra Energy, only 24 percent of the 15,000-strong workforce is female. The company did not return requests for comment.

“These are traditionally male-dominated jobs, and so they’re subject to the same forces as the rest of the economy that make it hard for women to enter,” said Carol Zabin, a labor economist at the UC Berkeley Labor Center who has studied the solar industry.

Zabin says the best way to solve the problem is through apprenticeships—because they are structured to train people on the job and support them. Bautista agrees: Having structured training both for apprenticeships as well as retention strategy makes it more likely that everyone has equitable access to opportunities, not just those who have the best relationships on the job.

When Bautista went to MIT, her engineering track cohort was already half women, and her first solar training was taught by two female electricians.

“I have been able to experience the things that kind of work in terms of women-only support spaces—mentors, sponsors, seeing pushes for equity,” she said.

Historically, Bautista’s experience is the exception rather than the rule. A 2017 report by the UC Berkeley Labor Center found that women made up only 2 to 6 percent of ironworker, electrician, and operator apprenticeships for renewable energy plants.

When AV Bourke shows up at her job site, she’s one of only two women on the ground—out of 15 or so construction workers installing solar panels. Bourke is a SolarCorps construction fellow at Grid Alternatives, part of an 11-month training program that aims to diversify the solar industry by helping its participants secure full-time employment once the fellowship ends. Last year, she competed in the Solar Games installer competition, part of the first all-women and nonbinary crew in the contest.

The job has been hard but worth it. “It’s a lot to learn, but it helps that I’m good with my hands,” Bourke said.

When the Fuller Project requested comment on the lack of women in the renewable energy workforce, the Department of Energy pointed to a page providing information on registered apprenticeships for women in the field, noting that they are “vastly under-represented."

Back at her job site, Bourke said that every day is a learning experience, and she’s loving the solar industry so far—despite the gender disparity. For others coming up in the field, she has a piece of advice: “If you are a newcomer, especially being a woman, it’s important to just go for it. You won’t know how good you are at something until you try.”

The Magazine of The Sierra Club

The Magazine of The Sierra Club