In California’s Monterey Bay Area, a Proposed Desalination Plant Divides Wealthy Communities and Poorer Ones

Residents of the town of Marina say it’s all a utility scam

Monterey Bay, California. | Photo by William Reagan/iStock

Few people would argue that California’s decade-long drought has been anything but a disaster. As in all disasters, there are some who seek to help—and others who are looking to capitalize.

On the picturesque Monterey Peninsula, critics accuse a private utility of trying to do the latter and profit off the area’s water scarcity. They say that the local water utility, California American Water (better known as Cal-Am), is pushing an expensive and largely unpopular desalination plant that, they complain, has pitted wealthy communities against poor ones.

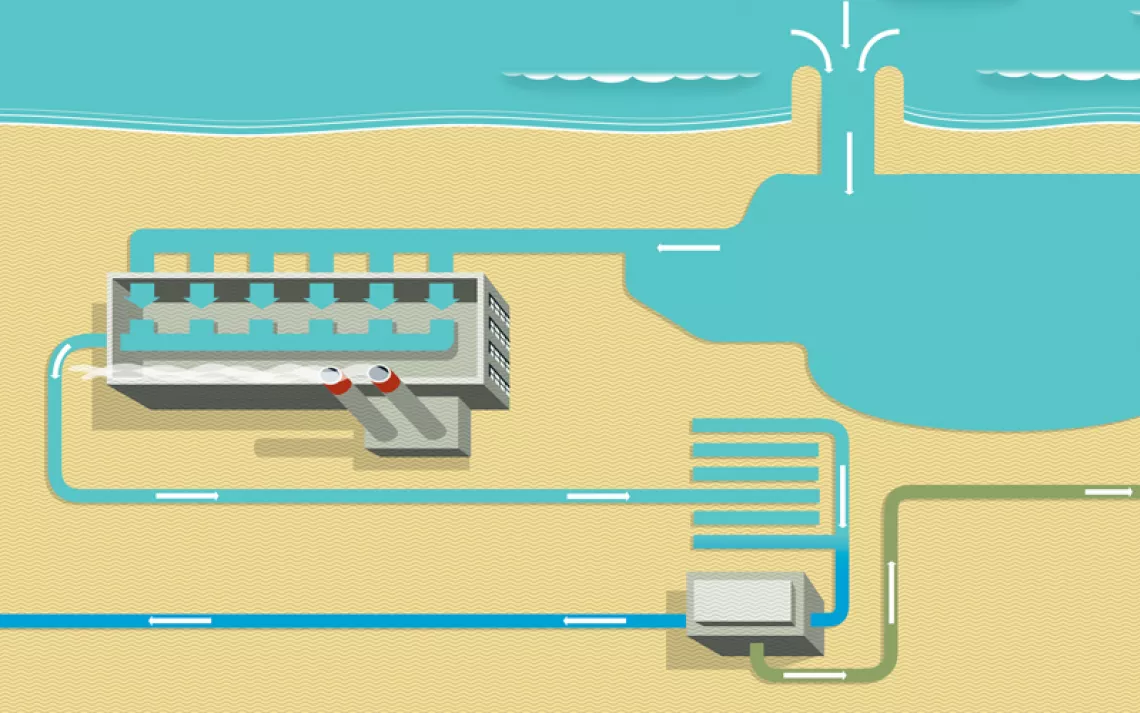

Last November, the California Coastal Commission approved a permit for a sprawling, $330 million seawater desalination facility in Marina—a blue-collar city of 22,500 residents that is located about 15 minutes north of the more affluent community of Monterey. If approved, Cal-Am’s desalination plant would produce 4.8 million gallons of freshwater per day and would be the first seawater desalination plant constructed in California in nearly a decade.

Marina mayor Bruce Delgado has been fighting the project, which he believes will change the complexion of the community and harm the local environment. He says his city would bear the industrial burden of the new plant while wealthier adjacent communities—Carmel-by-the-Sea, Pacific Grove, and Pebble Beach—would reap the benefits.

Marina, unlike its wealthy neighbors to the south, is an ethnically diverse and decisively working-class city. “There are approximately 52 languages and dialects spoken by Marina families,” Delgado told Sierra. Its residents—roughly two-thirds of whom are people of color—make on average $8,000 less per year than other residents across Monterey County. Many Marina residents work in the plush resorts around Pebble Beach or in the surrounding artichoke and strawberry fields.

Although Marina doesn’t need the water, Mayor Delgado says, ratepayers could see their water bills rise by more than 50 percent per month. The Monterey Peninsula already has some of the highest water rates in the country, according to a report from Food and Water Watch. “We don’t have the economic means of other nearby cities,” Delgado said. “Our city hall is in a 45-year-old mobile home. It was meant to be temporary … when we first incorporated, but we’ve never been able to build a civic center. We don't have any tennis courts. The only basketball courts we have are at the schools. We don't even have a swimming pool. These things are pretty basic."

What the city does possess is a beautiful location. Marina is situated along a windswept stretch of dunes that are home to dozens of rare plants and animals, including the endangered western snowy plover. Delgado says that public access to the coastline would be cut off by the sprawling footprint of the proposed plant. “We're finally getting rid of the last remaining coastal sand mine,” Delgado said. “But now, we're going to have to go through an industrial site to get to the beach.... If Cal-Am said they were going to put this plant on a beach in Monterey, I guarantee Monterey wouldn't have it.”

As the fight over the Marina plant continues, California has been given a temporary hydrological reprieve. A massive spring melt from one of the largest snowpacks on record promises to fill reservoirs while also threatening to inundate entire towns. But most water experts believe that one big precipitation year will not alter the fundamental shakiness of California’s water supply. As long-term aridification bears down on California, enthusiasm for desalination seems to be rising.

That enthusiasm emanates from the highest levels of state government. A leading proponent is none other than Governor Gavin Newsom. A report released by the governor’s office in August, titled California’s Water Supply Strategy, Adapting to a Hotter, Drier Future, advocates for expanding the state’s desalination capacity. “As California becomes hotter and drier, we must become more resourceful with the strategic opportunity that 840 miles of ocean coastline offer to build water resilience,” the plan reads.

“California, and the entire Central Coast, have endured many consecutive years of drought, and this trend is expected to continue,” said Josh Stratton, a Cal-Am spokesperson. “Conservation and reclamation of current water sources are essential elements of our water solution, but desalination is finally the drought-proof, reliable water source that has long been needed to solve our water crisis.”

The state currently has 12 seawater desalination plants, according to the State Water Resources Control Board. But only four are of utility scale and in regular operation. “Some people who live in these seaside communities look out at the ocean and see what appears to be an endless supply of water,” said Dave Stoldt, general manager of the Monterey Peninsula Water Management District. “It’s not that simple.”

Stoldt and other critics of the Cal-Am desalination plant believe that because of its huge costs, massive energy requirements, and potential for environmental damage, desalination should be considered an option of last resort. “We’re not necessarily against desalination as a form of water supply,” he told me. “But desalination is the most expensive resource, and it doesn’t make sense to go there until we have exhausted more affordable supply options.”

For years, Cal-Am has sought ways to increase its supplies after state regulators ordered the company to stop illegally diverting more than its allocated share of water from the Carmel River. And yet, Stoldt says that the company’s case for desalination on the Monterey Peninsula is built on shoddy math. Even factoring in growth projections, he said, there is more than enough water available from recycled wastewater along with improved groundwater management to meet the peninsula’s needs for decades to come. The Monterey Peninsula Water Management District along with local wastewater company Monterey One are expanding the capacity of the Pure Water Monterey wastewater treatment facility, which would supply an additional 2,250 acre-feet of water annually. Surplus water from the plant, Stoldt said, could be stored in surrounding aquifers.

Stoldt said misconceptions around drinking recycled wastewater are quickly fading. “The water is extremely high quality,” he said. “I sometimes have to remind people that a good part of the flow of the Carmel River comes from leaching septic systems.”

Recycled water is not only clean but also far cheaper than desalinated seawater—on average between one-third to one-seventh the cost of desalinated water, according to Michael DeLapa, executive director of local environmental group LandWatch Monterey. DeLapa says that Cal-Am’s push to build a desalination plant has less to do with creating an affordable and sustainable water supply than with maximizing profits for executives and shareholders. “These private, publicly regulated utilities generate profit as a percentage of capital investments,” DeLapa said. “If they are able to build a desalination plant, whether or not it is needed, that is a big capital investment.”

Connor Everts, executive director of the Southern California Watershed Alliance and a vocal critic of desalination, said he has seen interest ebb and flow over the decades. One season of heavy precipitation like what California experienced in the winter of 2022–23 is often enough to stifle interest for years to come, he said. He pointed to the early 2000s, when 11 small desalination plants were proposed between Santa Cruz and Monterey. “Most of those have gone away,” Everts said.

Whether California’s historic winter storms will diminish enthusiasm for the Marina plant remains to be seen. But for his part, Mayor Delgado says he won’t stop fighting until the plans are scuttled. “For decades, industrial facilities have been sited in poor communities of color, and it's no different here,” he said. “We already have the regional sewage treatment plant and the regional landfill. We have the regional outdoor composting facility and the regional sand mining plant. Now we're supposed to host this desalination plant.”

He continued: “We want to have more control of our destiny and not have someone else from outside our area force another industrial facility on us. We’ve already got more than our fair share.”

The Magazine of The Sierra Club

The Magazine of The Sierra Club