Building Black Community While Climbing Mount Kilimanjaro

Members of the first all–African American expedition to ascend the mountain share their stories

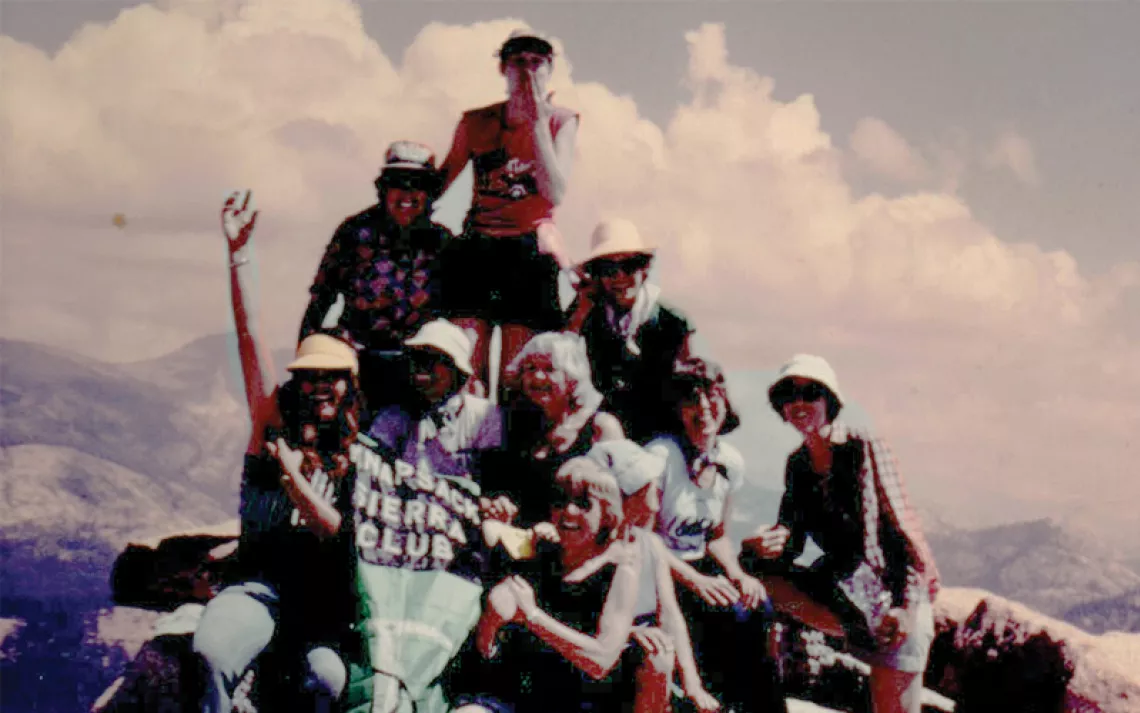

Photos courtesy of Outdoor Afro

When asked what was the most memorable part of climbing Mount Kilimanjaro in Tanzania this past July, few of the 11 members from the first all–African American team to tackle the peak mention reaching the summit. That wasn’t the highlight—not by a long shot. Instead, what has lingered in participants’ minds since their return was the rare experience of climbing and connecting with people who looked like them.

Valerie Morrow, who joined the expedition to mark her 60th birthday, says the revelation of experiencing the outdoors while being surrounded by other black people can’t be overstated. “Oh, my goodness. It’s beyond [being] represented. Everybody in the hotel was black. Everybody on the bus from Nairobi to Arusha was black. The team, of course, felt like family. It’s being in a group where you belong. Where you fit. Where you can bring your whole self. And you don’t have to justify it, or culturally adapt.”

Tarik Moore, a 34-year-old accountant and father of three living in the Philadelphia area, felt that spirit of belonging as soon as he touched African soil. Moore landed in Tanzania late at night, the last of the group to arrive. He was tired from the flight, and disoriented at navigating an unfamiliar country. Yet when Moore met the guide who came to drive him to Arusha, the gateway city at Kilimanjaro’s base, the words of welcome he received made a profound impact: Reaching for Moore, the guide said with a smile, “Welcome home.” From then, Moore knew this would be far more than a climbing trip. This was a reconnection with his ancestral identity. “It sort of hit me, then: I’m here.”

There are many reasons for assembling an exclusively black group of American wilderness leaders to climb the world’s largest freestanding mountain and, at 19,341 feet, the tallest in Africa. Outdoor Afro’s foremost motivation for organizing the trip is unequivocal: “We love black people.” Beyond community-building, though, is the drive to challenge stereotypes that portray black people as uncomfortable with, or totally unseen, in nature. The Kilimanjaro expedition provided an example of black bonding that was rooted in environmental stewardship, cultural education with African community, and nature exploration as a mental health benefit.

Even intra-community perceptions can go a long way toward making or breaking a person’s lifelong relationship with nature. Moore remembers growing up in Jersey City, where green spaces were rare or neglected at best. The city didn't bother investing in urban development in his part of town, and black families were more concerned with surviving than exploring nature. (Carl Anthony, the legendary urban planner and environmental justice advocate, termed this disparity in low-income neighborhoods as "spatial apartheid.") Moore says, "I was lucky to have both my parents. I had a family that cared, [who] wanted to see me get outside and do more than was typical for people in my area." His upbringing has fed into his own attempts at fostering comfort in nature among his children. "I bring them out to monthly Outdoor Afro events, to experience things I couldn’t when I was little–kayaking, camping, things like that. By the end, they don't want to leave! You want to be an inspiration to your kids, have them see faces that look like theirs in the things they want to do."

The Kilimanjaro expedition threatened to be grueling—six days, ascending through multiple climate zones—and so the team members undertook rigorous training before they reached Tanzania. In the year leading up to the trip, they were in constant contact, convening for weekly conference calls and checking in every few days to swap training anecdotes, or share bouts of nervousness and excitement. Each climber designed their own high-altitude endurance training: Some joined local climbing gyms or athletic groups; some left work early to do weighted runs around their metro area; others embarked on multiday backpacking trips at high elevation. “The Kilimanjaro hiking trails are nothing like what we have here,” says climber Raymond Smith, a 59-year-old U.S. Air Force veteran who works at the Bureau of Land Management and who was part of the Outdoor Afro team. “You’re waking up at eleven at night, doing four points of contacts with your hands and feet trying to get up a rock ledge. It’s hard to mimic that here.”

The training also helped the climbers prepare emotionally for a journey that many wouldn’t have imagined themselves undertaking. For Morrow, joining a local triathlon team for women over 50 forced her to re-evaluate the way she thought about her body. “I’ve never done anything like that before. I would’ve run for the hills, if someone had suggested I join a triathlon team. But it meant physically feeling great: joints that hurt, [when they’re] worked out a lot, feel great. That was life-changing.” There was also the anticipation of going many days without family. At the suggestion of a fellow Outdoor Afro leader, Moore began reading Geronimo Stilton: Mighty Mount Kilimanjaro, a children’s book about a mouse who climbs Kilimanjaro with his adventurous friend, a hyena. His daughter read along with him, and the story helped her contextualize what her father was about to undergo. “I’d read a section every night,” Moore says. “The book talked about the mountain: different biomes, how long it would take, what Geronimo experienced at different elevations. When they were showing all the things he packed, my daughter said, ‘You have a sleeping bag too, right?’ She started going through and comparing the things I’d need with his list.”

Kilimanjaro’s location was as essential to Outdoor Afro’s choice as its height. It was important to everyone that they connect with black culture in Africa, and get to know the people of Arusha. From the moment the team arrived, the community embraced them. “Going to the continent for the first time, and being in a new environment with mostly black people, was indescribable,” Moore says. “We melted into a family.”

“Family” is how most of the team describes the relationship they developed with Arusha locals. “You should’ve seen the looks on their faces,” Smith recalls. “The smiles. The welcoming. The hugs. It was like we were a part of their family already. To go to the continent where our people originated from, and to feel that kind of love . . .” Smith pauses, trying to find the words. “That level of comfort is a lot different than what you feel at home. We were about to do a daunting, physical challenge, but when we met the people, we all took a breath and said, ‘We can relax. I think they got us.’”

The team knew that some foreign visitors beelined straight to Kilimanjaro without really seeing Arusha or its people, so they got proactive about creating cultural bridges. All the climbers learned some Swahili as part of their training, which helped them quickly connect with their porters and guides. Many packed extra essentials to give as tokens of thanks: socks, shoes, jackets, gloves. “They were more open to us,” Moore remembers, “because we were trying to learn their culture, instead of just coming in and saying, ‘OK, we’re going to come and conquer this mountain.’” Morrow, who spent extra time with the porters due to resting at camp during the final ascent, felt a kindred spirit. “We talked, laughed, and sang with them. We would see other climbing groups on the mountain, and we were clearly more connected to our guides and porters, just in our body language. When you saw other groups and their guides, the body language was so different.” Smith sums up the intimacy they developed with their Tanzanian crew: “They had our lives in their hands, and they took care of us. I have nothing but respect for those guys."

Kilimanjaro, which is located just south of the equator, has five distinct biomes across its three-and-a-half-mile-high elevation. The first zone is cultivated land, receiving the most annual rainfall and dotted with coffee plantations. Above the plantations are Kilimanjaro’s famed rainforests, unique for a high-elevation mountain, full of monkeys, birds, and species endemic to sub-Saharan Africa, like the aardvark. Spreading above the jungles are the frigid, misty heath-moorland zone, followed by the alpine desert. Finally, there is the Arctic-like summit, where climbers trek through glaciers and fresh snow. Passing through each zone, the Outdoor Afro team touched a wild, majestic aspect of nature that dwarfed the humans crawling through it.

“It pulled you into being present in the moment, of being in that land,” Smith remembers. “One day, we were around lush greenness; on the next, we were on the moon, a lunar landscape.” Smith developed fluid in one lung during his acclimation, and later caught frostbite. Each challenge was a message from the mountain. “That was Mother Nature saying, You must respect Me. That’s what that was. I will never take that for granted.”

Morrow remembers feeling nestled in the vast presence of the mountain, held within the hand of nature. “We slept above the clouds. You heard word that it was raining down in Arusha, but we’d have this beautiful blue sky above us. Looking out over the valleys, you could see the trail for a couple miles ahead. Because I was far behind the rest of the group, I could look up at them. I could always tell where it was headed. It was very joyous.”

Of the 11-person group, five climbers made it to the top. They barely mention it, though, as if summiting Mt. Kilimanjaro was a lesser outcome. “Most of us went as high or higher than we’ve ever been,” says Smith, who made it to the top. “We consider that a summit. You may not have gotten to the sign [at the top], but you have summited. We know the effort that everybody put into climbing that mountain, and that grows a new level of respect.”

After completing the climb, most of the team continued to the Serengeti for a safari trip, where they learned about the local Maasai culture and explored the area’s history. The leadership skills that they gleaned from the trip will be disseminated throughout the Outdoor Afro network here in the United States. “It’s nothing but a boon for Outdoor Afro,” Smith says, “for we came back better leaders, and we’re going to share that across our networks—and across the black community.” When asked how he has integrated the experience of climbing Kilimanjaro into his life since returning, Smith is all excitement. “I spoke to a school that’s predominantly students of color, who followed our trip the whole time. The teacher said she wanted them to see a person of color who’s done something like that. I was so excited to talk to those kids and tell them the world is waiting for them to do the same thing.”

The Magazine of The Sierra Club

The Magazine of The Sierra Club