Black History Told Through America’s Public Lands

Check out these monuments, parks, and sites on your next outdoor adventure

The National Museum of African American History and Culture in Washington, DC. | Photo by traveler1116/iStock

The mere mention of outdoor recreation often evokes the grand: the sweeping valleys of Yosemite National Park or days spent trekking the sprawling Appalachian Trail. Of the hundreds of parcels of public land, these are frequently the stars of the show, drawing in millions of visitors annually, attracting filmmakers, and being lovingly documented on Instagram. But there are other attractions worth celebrating, not just for their beauty but for their dedication to preserving American history, especially Black history.

There are historic sites that invite you into the inner sanctums of leading abolitionists and civil rights activists, such as the homes of Frederick Douglass and Mary McLeod Bethune, both in Washington, DC. Other public sites honor places where pivotal moments in history occurred, such as the Selma to Montgomery National Historic Trail, a 54-mile route that commemorates the path of the 1965 Voting Rights March in Alabama. In neighboring Jackson, Mississippi, the residence of prominent civil rights activists Medgar and Myrlie Evers has been a national monument since 2019. The site preserves their home and memorializes the life of Medgar Evers, whose assassination in the home's carport served as the catalyst for the passage of the Civil Rights Act of 1964.

In addition to honoring significant places and celebrating the lives of these individuals, these sites remind the living how far we have come as a society, and what's at stake if we don’t continue to advocate for justice and equality. As presidential candidates proclaim that America isn’t a racist country, these sites reveal the blood and pain etched into our nation's history. But they represent so much more than tragedy. They are also testaments to the resilience of people and the power of collective action. Black people, their spaces, and their stories have left an indelible mark on society, and these sites commemorate that heritage. Here are a few more sites to consider visiting when you want to learn about Black history with the added benefit of also enjoying the great outdoors.

Emmett Till and Mamie Till-Mobley National Monument

Roberts Temple Church of God in Christ, where Emmett Till's open-casket funeral was held in 1955. | Photo by Alexandra Buxbaum/Sipa USA via AP

Designated by President Biden in July 2023, the Emmett Till and Mamie Till-Mobley National Monument is America's newest national monument dedicated to ensuring we never forget the brutality of bigotry. It honors the death and legacy of Emmett Till, who, at 14 years old, was kidnapped and murdered by two white men after a white female store clerk accused him of teasing her. This is one of the few national monuments spread across multiple states. Its sites include Graball Landing in Mississippi, near where Till's body was recovered from the Tallahatchie River. A commemorative sign has marked the area since 2008, but vandals continuously deface it and frequently pierce it with bullet holes. In 2019, the Emmett Till Memorial Commission erected a bulletproof sign. The second site is the Tallahatchie County Courthouse, where an all-white jury acquitted the two men who murdered Till. The last site is the Roberts Temple Church of God in Christ in Chicago, Till's home city, where his mother famously held an open-casket funeral so that people could see what racism had done to her boy.

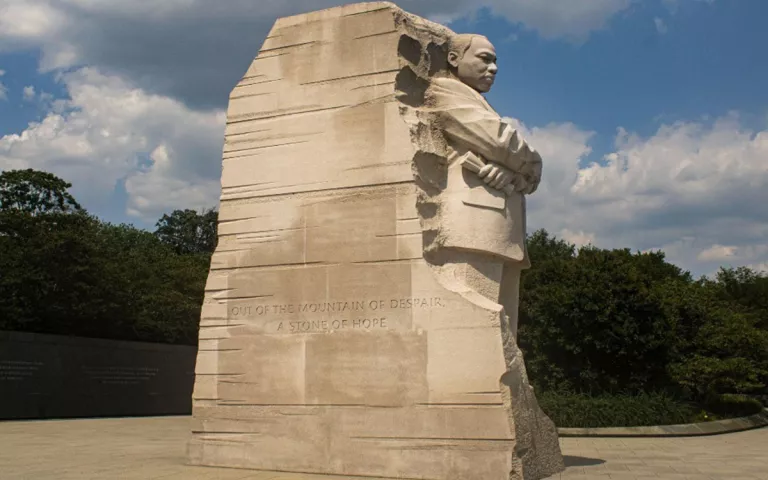

Martin Luther King, Jr. Memorial

The Martin Luther King, Jr. Memorial at the National Mall. | Photo by Abdul Gueye/NPS

The Martin Luther King, Jr. Memorial, along Washington, DC's Tidal Basin, is the first memorial on the National Mall to honor the life of a Black person. While there are no buildings around the memorial, the official address is 1964 Independence Avenue SW, a nod to the year the Civil Rights Act became law. As a leading figure in the civil rights movement, Dr. King was pivotal in helping pass that law, and he also advocated for the Voting Rights Act of 1965. The monument officially opened on the 48th anniversary of the March on Washington, where Dr. King delivered his famous "I Have a Dream" speech. Today, visitors enter the memorial through two large boulders called the Mountain of Despair. After passing through, they emerge in front of a 30-foot-tall granite carving of Dr. King rising from a stone called the Stone of Hope. Both the mountain and stone refer to a quote from the speech. A crescent-shaped 450-foot-long wall of Dr. King's quotes surrounds his statuesque likeness.

George Washington Carver National Monument

Statue of the young George Washington Carver. | Courtesy NPS

Known as the "Plant Doctor," George Washington Carver was a renowned scientist who pioneered methods of crop rotation and soil regeneration well before they became farming fads. Born into slavery in southwestern Missouri, Carver's knowledge and talent, especially as it related to the cultivation of peanuts, received international acclaim by the time he reached adulthood. In 1943, just months after Carver's death, President Franklin D. Roosevelt created the George Washington Carver National Monument, preserving the estate where Carver was born. The 240-acre national monument dedicated in Carver’s honor consists of his childhood home, a welcome center, and a cemetery, all set against sprawling woods, trails, and information plaques detailing Carver's life. The site is the first national monument devoted to someone who wasn't president and the first to celebrate the life of a person of color.

Harriet Tubman Underground Railroad National Historical Park

Harriet Tubman Underground Railroad National Historical Park, Dorchester County, Maryland. | Courtesy NPS

In 2013, President Obama created the Harriet Tubman Underground Railroad National Monument using the executive powers of the Antiquities Act, which authorizes presidents to single-handedly protect cultural and historical sites. The following year, Congress established the national historical park, which sits within the monument. The 480-acre site, on Maryland’s Eastern Shore, is the childhood home of famed humanitarian Harriet Tubman, and on its grounds, guests can stop by the visitor center to see exhibits, films, and artifacts or venture outside and check out stops along the Underground Railroad. Tubman returned to this area several times after escaping to freedom to help others emancipate themselves. Helping visitors envision what the area would have been like when Tubman lived here, people are encouraged to also explore the adjacent Blackwater National Wildlife Refuge, a 25,000-acre sanctuary for public recreation, learning, and wildlife protection. This area is also one of the first stops on the Harriet Tubman Underground Railroad Scenic Byway, a 125-mile road trip that starts in Maryland, wends through Delaware, and ends in Philadelphia.

Boca Chita lighthouse at the entrance to Boca Chita Key Harbor at Biscayne National Park in Florida. | Photo by Claudia Cooper/iStock

The Jones family is one of the greatest Black families in the land conservation movement that you’ve probably never heard of. It’s because of their family’s estate, the first parcel of land owned by a Black family in Florida, that we have Biscayne National Park, a 172,000-acre protected area seven miles off the coast of Miami. The area, which is at the northern edge of the Florida Keys, was first purchased by Israel Jones in the 1890s in an area that many white farmers on the mainland had deemed undesirable. Undeterred, Israel purchased several islands, built a home, and cultivated limes. Israel’s two sons, Sir Lancelot and King Arthur, held onto the property well into the 20th century and became fishing guides when they decided to no longer farm the area. In the 1960s, developers started to eye the property, with the sons reportedly refusing several offers to buy the land. Instead, they wanted to preserve it. President Lyndon B. Johnson designated the area as a national monument in 1968, two years after King Arthur’s death. Congress elevated the area to national park status in 1980.

Future Sites

To this day, the story of national monuments and parks dedicated to Black history is far from complete. Advocacy groups, civil rights leaders, and environmental-justice organizations are still fighting to protect spaces that keep history alive. As recently as December 2023, Democratic New Jersey senator Cory Booker and Republican Oklahoma senator James Lankford introduced legislation to protect “Black Wall Street,” a famed section of Tulsa’s Greenwood neighborhood where Black commerce thrived before a mob of white terrorists besieged the area in 1921. During a June evening that year, at least 300 Black people were killed, and dozens of businesses were burned to the ground. Local groups, such as the Black Wall Street Coalition, have been urging President Biden to use the Antiquities Act to declare this area a national monument since at least 2021, but efforts to study the potential for a protected area honoring the area have been ongoing for nearly two decades.

Like the massacre in Tulsa, the site of the 1908 Springfield race riots is one that marks terror and pain. White residents looted and destroyed Black neighborhoods and businesses in this Illinois town after learning that the sheriff had moved two Black men accused of crimes—and who the mob intended to lynch—out of the city for their safety. The destruction was so great that many Black residents moved, never to return. The events, which occurred over a two-day period, helped spark the creation of the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP). Illinois state leaders submitted legislation to create a national monument in 2021, but the bill languished. Advocates, including the NAACP and the Sierra Club, are now hoping President Biden will designate the area as a national monument for its history and archaeological artifacts. Doing so would honor the people who lived here, the lives that were lost, and the effect the riots had on American history.

The Magazine of The Sierra Club

The Magazine of The Sierra Club