Best Astronomical Highlights of 2019

What to look out (and up) for this coming year

Photo by dariustwin/iStock

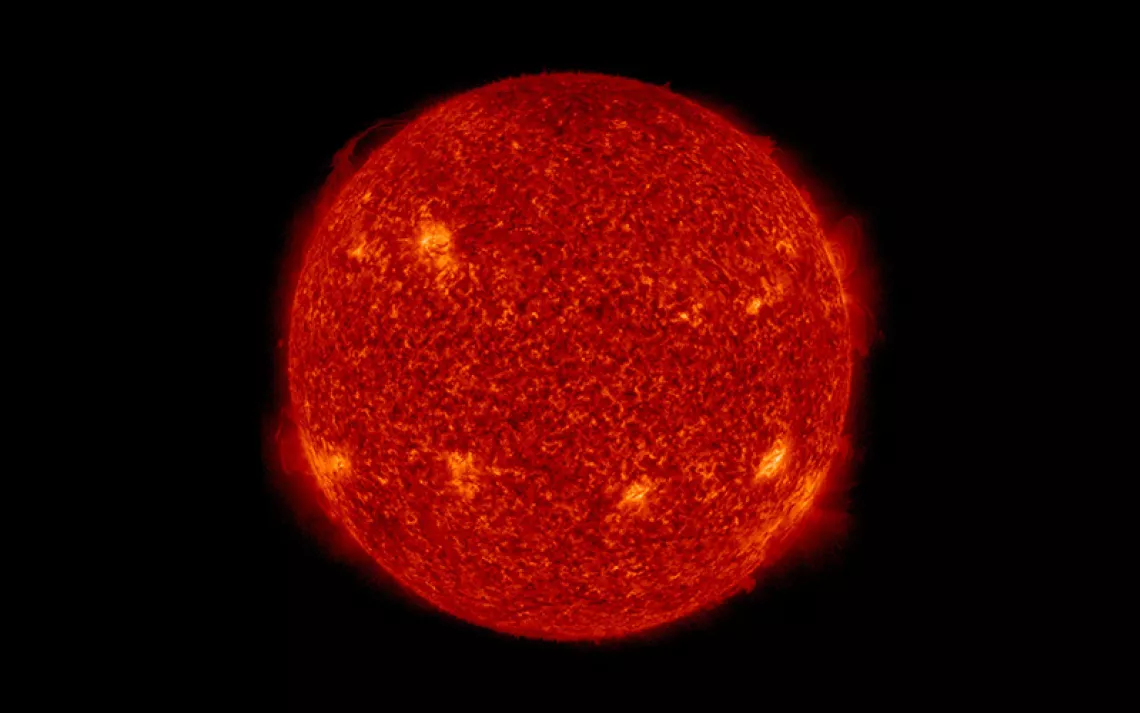

Lunar and Solar Eclipses

2019 will be a big year for eclipses, with two occurring in January, two in July, and one in December. The total lunar eclipse, which is the easiest to view, will also be the most accessible to anyone living in North or South America. On January 20, the moon will slide into Earth’s shadow and turn orange-ish red. Expect to hear the term “Blood Moon” for this eclipse, even though, depending on your location, particulates in the atmosphere from events such as wildfires may cause the lunar eclipse to appear purple-ish or even black.

The lunar eclipse will be even more spectacular because it coincides with an extra large moon, or supermoon—the first three full moons of the year will be supermoons because they occur during perigee (when the moon is closest to Earth). The total stage of the lunar eclipse starts at 11:41 P.M. on the East Coast and 8:41 P.M. on the West Coast, with the partial stages beginning and ending about an hour before and after total stage. The moon will stay totally eclipsed by Earth’s shadow for approximately one hour and be visible to virtually everyone in North and South America except where the view is ruined by clouds.

The second lunar eclipse of the year is a partial eclipse that is centered over Africa and the Middle East on July 16/17. The solar eclipses are also far-flung from the contiguous United States. A partial solar eclipse occurs on January 5/6, visible from the west coast of Alaska and northeastern Asia. The first total solar eclipse since the Great American Eclipse in 2017 is on July 2 in Chile and Argentina. Finally, an annular eclipse—when the edge of the sun remains visible as a bright ring around the moon—will occur on December 26 near the Indian Ocean.

The Comet of 2019

Comet Wirtanen showed up in the night sky in December, but it lingers into January enough to hopefully still be a decent viewing target. The comet is near overhead on January evenings, headed toward the bowl of the Big Dipper. The full, fuzzy body of the comet means its total brightness is spread out, so it won’t be a snap to spot. But part of being in the amateur astronomer club is standing outside on cold, dark nights and getting excited when a faint, barely perceptible greenish-blue fuzz enters your binoculars' field of view.

100 Meteors an Hour

A few annual meteor showers regularly produce a predictable onslaught of debris raining down from the solar system. The three best are the Quadrantids on January 3/4, the Perseids on August 11/12, and the Geminids on December 13/14. All three showers can produce meteors for a week or more around their peak, but on these dates it is possible to see up to 100 meteors an hour. If you can, stake out a spot in the countryside away from city lights in order to really enjoy the show.

The Summer of Gas Giants

Jupiter and Saturn both reach opposition in the summer months, meaning they’ll be visible almost the whole night long, giving anyone with telescopes a great chance to explore rings, moons, and more.

Jupiter reaches opposition on June 10. The planet reveals much character with optical aid, including dark and light bands, four ever-rotating satellites, and for the eagle-eyed observer, a peachy oval known as the Great Red Spot.

Saturn reaches opposition on July 9. It’s currently positioned like you would expect based on classic, storybook-type images, with its rings tilted toward our view, unlike other times when it is angled in such a way that the rings are edge-on to us and almost disappear. In 2019, the view will be majestic, with the rings making the planet look twice as wide.

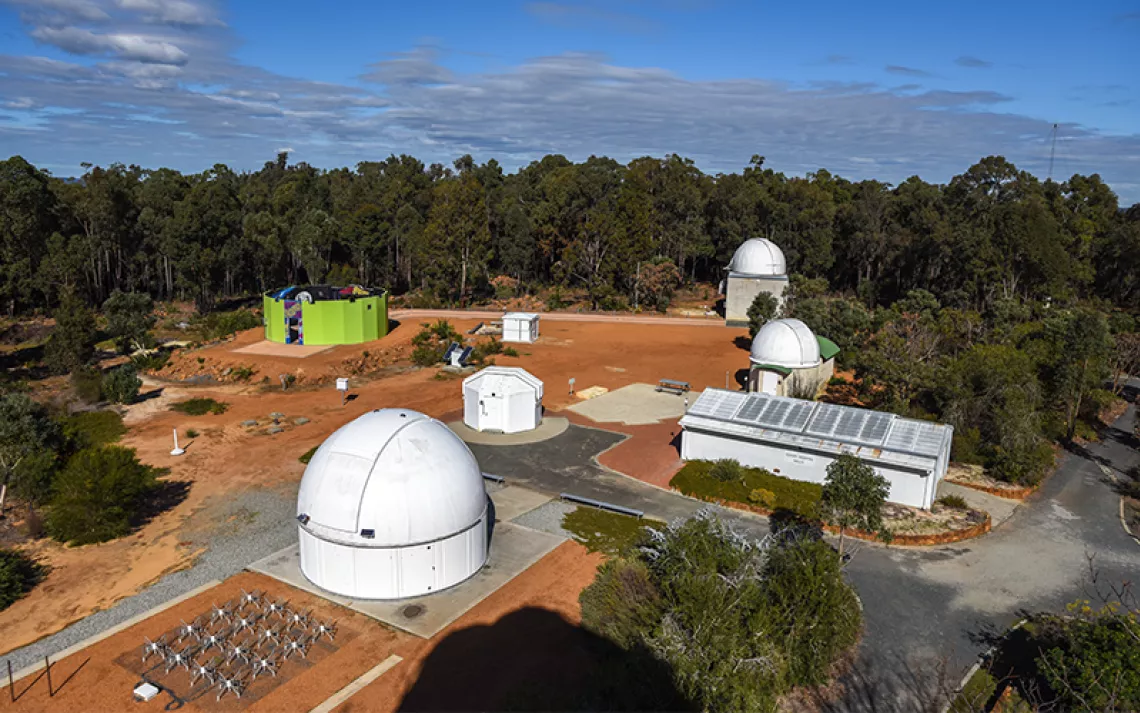

Transit of Mercury

On rare occasions, Mercury will pass right in front of the sun as seen from Earth. While Mercury is too small and far away, and the sun too large to create a solar eclipse like the moon does, the black dot of Mercury on the surface of the sun can still be seen with the right equipment, namely a large telescope and a solar filter. Mark your calendar for the morning of November 11 and find a local observatory that is open to the public so you can watch this uncommon event.

Asteroid Vesta Brightens

Most people have never seen an asteroid, but Vesta, the second largest and the brightest asteroid, gives us an opportunity in November. Vesta reaches opposition on November 12. Its magnitude can vary during opposition, and this year it will be around magnitude 6.5, within grasp of anyone who has excellent vision and is in a dark enough location, and visible to almost all of us with the help of binoculars. The trick to finding Vesta is having a good finder chart so you can star-hop to exactly the right faint point of light in the night sky.

Try looking for Vesta on November 6, when the V shape of the Hyades in Taurus will point the way. This V shape can be used as an arrow that aims toward a pair of magnitude-3.6 stars known as Xi and Omicron Tauri. On this date, Vesta will be less than half a degree from Omicron Tauri. In a telescope with a 1-degree field of view, you will be able to fit both Xi and Omicron Tauri along with Vesta. The best way to be sure you’ve seen Vesta is to come back the next night and see if the target has moved. Sketching the field of view from one night to the next also helps to spot the silent solar system interloper.

The Magazine of The Sierra Club

The Magazine of The Sierra Club