August Stargazing: Comet Neowise, Instagram Star

The internet sensation will be visible until the middle of the month

Photo by Deirdre Miller

We’re standing on a sage-covered mountainside on the California-Nevada border, in the sliver of dusk before the onset of night. One by one, the stars flicker into view. My 14-year-old daughter, Deirdre, has attached her camera to a compact tripod and is pointing it at a fuzzy streak of light in the northern sky. She’s a tough hiker and a lover of the outdoors—and like many girls her age, a denizen of social media. Tonight, she’s looking to capture an image of Comet Neowise, an object that has flashed through the public imagination and through Facebook, Instagram, and Twitter feeds around the world.

Though the foregrounds of the images on social media are different, the subject is invariably the same: Neowise over the ocean; Neowise blazing through the light pollution of Los Angeles; Neowise suspended above the monoliths of Stonehenge. One clever composition shows two people with tennis rackets in silhouette, knocking the comet back and forth like a glowing shuttlecock.

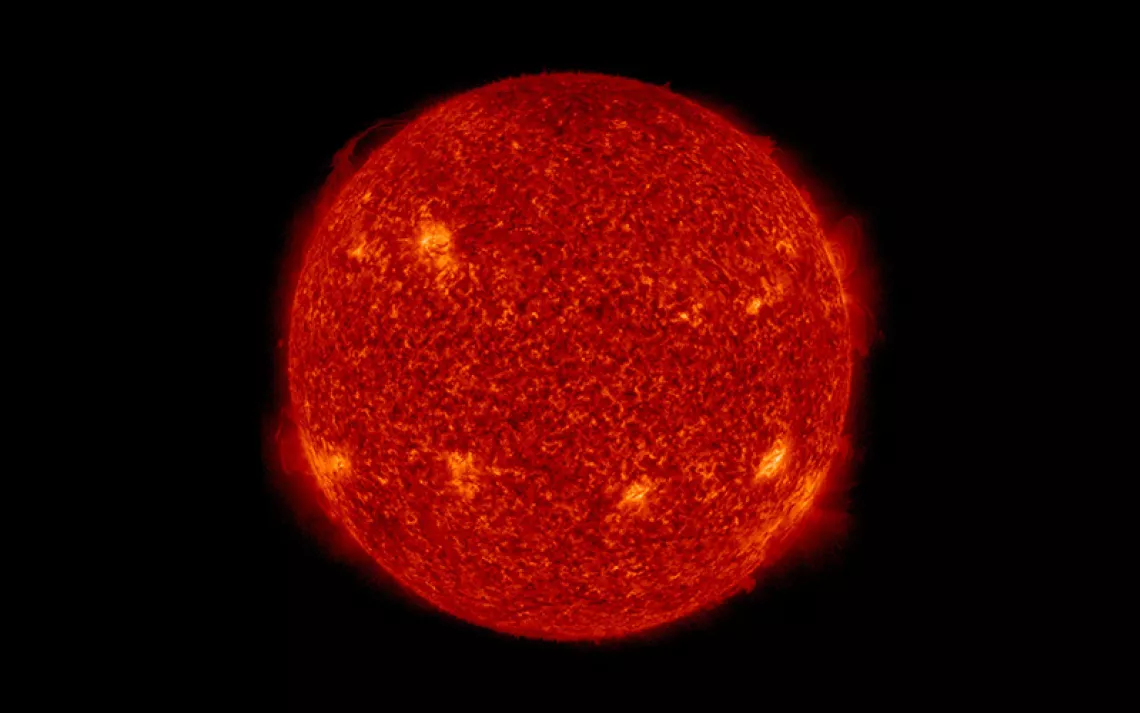

When Neowise began its rapid brightening at the beginning of July, it became the first comet since Hale-Bopp in 1995–1997 that was bright enough to be seen by city dwellers, offering the display that two much-hyped comets, Atlas and Swan, failed to deliver earlier this year. Its unwieldy name (an acronym for NASA’s Near-Earth Object Wide-field Infrared Survey Explorer, the instrument that discovered the comet in March) belies the fervor it has touched off.

In the past two weeks, I’ve watched in awe as friends and acquaintances—folks who have never expressed the slightest interest in space, mind you—post stunning images of Neowise online. Take, for instance, a former colleague, a fine and perceptive person, to be sure, but never one to gush about wonders of the cosmos, who managed to snap a magazine-worthy photograph from the outskirts of Boston. Even my dad (who, to be fair, was a hobbyist astronomer in the 1980s) has been gripped by comet fever. Last week, he called me out of the blue asking me to walk him through the complicated menus of his DSLR camera, to find the best settings for capturing the comet.

#NEOWISE has officially become an astronomical internet sensation. But why?

Certainly, some of the interest has to do with the pure visual beauty of the object itself. The misty fuzz of the comet’s core fading into a wispy arcing tail is something out of a fairy tale—archetypical, dreamlike, a shooting star as drawn by a third grader. I have heard others describe an innate fascination with the idea that such a small and distant object can, for a brief moment, become the most striking object in the night sky. A sense of urgency may also be driving us, camera in hand, into the night: Unlike Halley’s Comet, which returns to Earth on 75-year intervals, Neowise will not be seen from Earth again for thousands of years. Once it’s gone, it’s gone. The coronavirus pandemic may also play a role, stirring within some of us a more universal outlook—a coming to terms with the notion that the collective survival of our planetary family depends upon our willingness to work together.

But those explanations don’t fully account for the social media phenomenon. I think that Neowise’s popularity has a lot to do with the fact that so many of us have in our possession the gear needed to capture dazzling images of it. Some new smartphones, for example, are equipped with digital sensors so sensitive that one can snap a photo of the comet without having to attach it to a tripod. "The Neowise craze seemed to be fueled by good amateur astronomer photographs in late June, which I think caused the media hype,” Stan Honda, an astrophotographer and board member of the Amateur Astronomers Association of New York told me. Aside from the telescope itself, no other innovation has allowed us to engage with the intricate structures of space as intimately as digital photography.

Neowise above Central Park. | Photo by Stan Honda

And yet, I can’t help but wonder—as technology has leveled the playing field, allowing anyone with a digital camera to shoot the comet and share the images instantly across the expanding universe of the internet—whether something is being lost in translation.

Those old enough to witness Halley’s Comet’s appearance in 1986 probably recall not just the comet itself but also the rituals undertaken in order to see it. Though I was only nine at the time, I remember in vivid detail the smell of coffee, the feel of the rough upholstery on the seats of my dad’s Ford Bronco, the music on the FM radio, notably, Don McLean’s “American Pie,” fading into static as we pressed further onto the eastern plains of Colorado. I can still feel the tingle of the frigid air on my face, fingers, and toes as we stepped onto the snow-crusted prairie. Our goal wasn’t to capture the comet. It was to experience it.

“I think I got it,” Deirdre says excitedly, peering at the LCD screen. She has indeed. The white streak of Neowise above a distant, pine-stippled ridge is unmistakable. Though Neowise won’t return for another 6,800 years, its image is sure to drift across the internet for decades to come. As we zoom in and examine more closely the comet’s brilliant silhouette, I wonder what light is more indelible, the blue-green smear of Halley’s that lives in my memory or the small bright streak rendered in pixels on the screen of the camera?

At this moment, I’m reminded of the essayist Annie Dillard’s words of caution to the aspiring memoirist: “If you prize your memories as they are, by all means avoid—eschew—writing a memoir. Because it is a certain way to lose them. . . . The work battens on your memories. And it replaces them.” Does it make me sound old-fashioned (or worse in these tech-obsessed times, a Luddite) to fear that the digital pursuit of Neowise could have a similar effect?

Will Deirdre recall the rough road we negotiated, the swifts and bats zipping through the deep blue of dusk, the sudden chill of night as the Milky Way emerged overhead? Or will those memories be supplanted—replaced—by the mechanical half hour we spent setting up her tripod and camera or the hour of sustained concentration, staring into digital space, as the images piled up, one after another, on the digital display?

Will she remember the comet of the sky or the comet of the screen?

WHAT TO LOOK FOR IN AUGUST

Though Comet Neowise is dimming rapidly, most experts believe it will be visible until mid-August. Beginner astronomers, take note: Patience will be required to see it as it races away from Earth. What was once an obvious streak is now the merest of wisps, becoming ever fainter as the moon increases in brightness. Neowise is visible just after sundown, low on the northwestern horizon. To see it effectively, you’ll need a pair of binoculars or, ideally, a camera and tripod. Using 10 to 15 second exposures, you should be able to tease it from the encroaching glow of the moon. Since the comet will no longer be visible to the naked eye except in the darkest locations, use this handy star map at Earthsky.org to pinpoint its location.

As Neowise recedes from view, one of the most spectacular annual astronomical events will be getting underway—the Perseids meteor shower, which can yield up to 100 bright fireballs per hour. Annual meteor showers like the Perseids occur when Earth passes through bands of debris left behind by comets as they hurtle through space. The brilliant flashes are produced by small fragments that enter Earth’s atmosphere, most of which are no larger than a pebble.

The center of this shower’s meteor activity, known to astronomers as the “radiant,” is found in the constellation Perseus—named for the Medusa-slaying hero of Greek myth. At this time of year in the northern hemisphere, Perseus rises in the late evening, just below the prominent W-shaped constellation Cassiopeia. In terms of numbers of meteors per hour, the shower will peak in the days preceding August 15. The best viewing, however, will most likely happen in the days following the 15th, as the moon fades from view and the sky darkens to reveal even the smallest of streaks.

This month’s full moon arrives on August 3. Tribes of the northeastern United States referred to it as the Sturgeon Moon because it was at this time of year that the pallid prehistoric fish were caught in large numbers from the Great Lakes. Be sure to catch the nearly full moon on the early evening of August 2 as it passes close to Jupiter, which, in turn, is trailed closely by the ringed-planet Saturn.

The Magazine of The Sierra Club

The Magazine of The Sierra Club