In Appreciation: Jerry Mander (1936–2023)

How a radical ad man helped David Brower create the modern Sierra Club

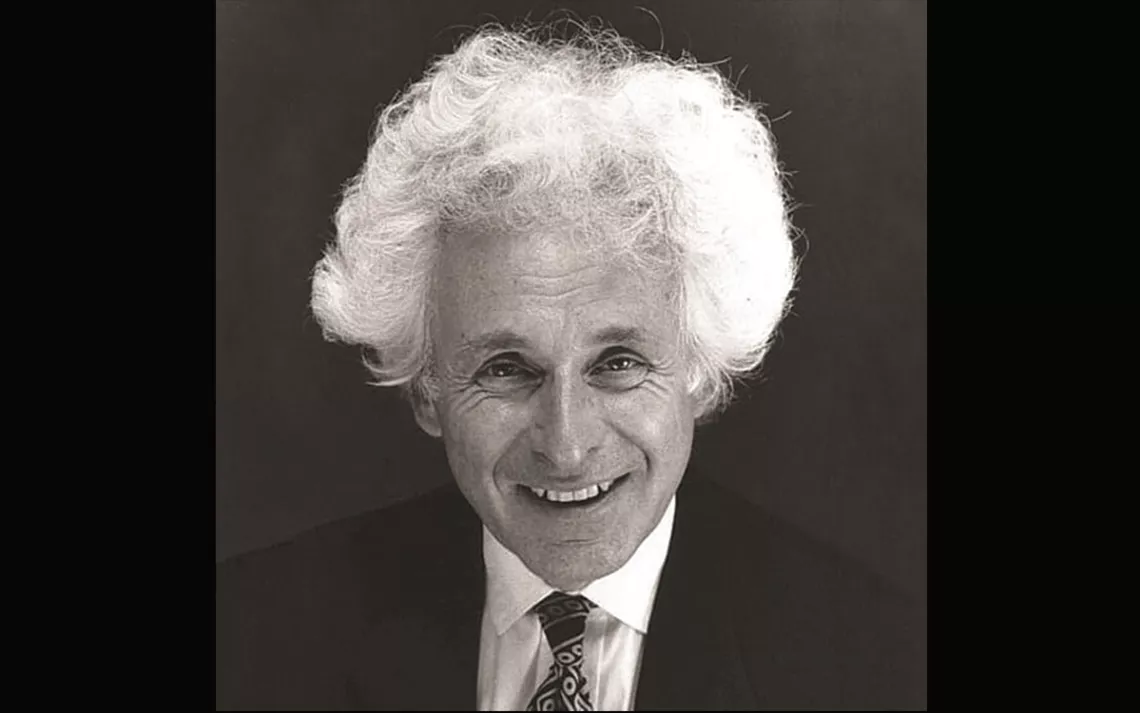

Jerry Mander | Photo by Mikkel Aaland

The Sierra Club was established in 1892, and it took about 74 years for the organization to accumulate its first 40,000 members. Then, between 1966 and 1968, the membership number doubled to nearly 80,000 people. There were two main reasons for this skyrocketing membership: the Internal Revenue Service and a man named Jerry Mander, who passed away last month at the age of 86.

Mander was born to Eastern European immigrant parents who had no idea what the name would make people think of in America. In fact, Mander’s given name was Jerold, but he was Jerry all his life.

He grew up in New York City, studied economics at the Wharton School and Columbia but was attracted to advertising. He applied to several firms but got no offers. He later learned that at that time the big firms wouldn’t hire Jews, though they wouldn’t admit it.

He worked briefly for a public relations firm in New Jersey, then headed west to visit a friend in San Francisco. It was love at first sight.

He landed a job doing publicity for the San Francisco International Film Festival and then struck out on his own doing publicity for various left-leaning organizations. One was The Committee, an improvisational theater group that was fiercely opposed to the Vietnam War.

The Committee’s antics—including several newspaper ads—caught the eye of the legendary adman Howard Gossage, who was famous for, among many achievements, a series of ads in The New Yorker extolling the virtues of Irish whiskey. Gossage asked Mander if he might be willing to join his agency. This was in 1966.

It just so happened that the Sierra Club was at that time locked in battle with the US Department of the Interior, which wanted to build two big power dams inside the Grand Canyon. The Interior Department, under the command of Stewart Udall, who was a friend to the land in most particulars but not this one, was winning. The Sierra Club and its allies had rallied their supporters as best they could, but things were looking grim.

David Brower was the executive director of the Sierra Club at that time, the group’s first-ever, having been hired in 1952 after many years as a volunteer. Brower had seen some of Gossage’s ads, which he admired for their style, their content, their humor, and their typography. Brower thought the right ad in The New York Times might just shake things up enough to derail the dams.

Brower had written some copy for an ad, which he took with him for an unannounced visit to Freeman & Gossage, located just a half-dozen blocks from the Sierra Club’s offices. He introduced himself to Gossage, who summoned Mander to join them. Gossage and Mander were horrified at the prospect of defiling the canyon, but they thought Brower’s draft was terrible. They agreed to write a new version of the ad.

Brower, Gossage, and Mander couldn’t agree on which ad to run. They argued and debated and eventually decided to have a competition. They persuaded The Times to print the Brower version in half of the papers on the appointed day and the Mander/Gossage version in the other half of newspapers. The Brower version included a coupon to be mailed to the Sierra Club with a contribution, or asking for more information. The Mander version included seven coupons—to the Sierra Club, to Interior Secretary Udall, to members of the House and the Senate and other officials.

The two ads were published on June 9, 1966. Mander & Gossage won the contest, though it’s unclear by how much. Brower said the Mander version out-drew his by three to two, as measured by coupons returned to the Sierra Club; Mander remembered winning by more like three to one.

Either way, the ads were a sensation. Udall and members of the House and Senate were flooded with coupons and angry letters from people furious at the prospect of dams flooding the Grand Canyon.

An equally dramatic reaction came from the Internal Revenue Service, which sent an agent the very next day to the headquarters of the Sierra Club with a letter informing the organization that the IRS was reviewing the organization’s tax-deductible status and could no longer promise that contributions to the group would be deductible from income taxes. Large contributions immediately plummeted, costing the organization thousands of dollars. (The Sierra Club’s tax-deductible status was later yanked permanently after some wrangling in the courts; today the Sierra Club is a 501 c4 organization, which allows it to lobby members of Congress and make political endorsements.) But the persecution of the Sierra Club by the IRS for the crime of trying to save the Grand Canyon became a huge story and inspired sympathy and support for the organization, whose membership soared.

This was just the beginning.

Mander wrote, and the Sierra Club published, more ads opposing the Grand Canyon dams. The headline on the most famous one read, “Should We Also Flood the Sistine Chapel So Tourists Can Get Nearer the Ceiling?” The dams were never built, marking one of the most important political victories of the American environmental movement in the 1960s. Mander went on to write ads in support of national parks in the redwoods and the North Cascades and a controversial one calling for seeing the whole planet as “Earth National Park.”

Howard Gossage died in 1969, and his agency folded soon after. Jerry Mander and some friends then founded Public Interest Communications, abandoning commercial work for good. They produced ads for environmental organizations, Indigenous groups, Planned Parenthood, gun-control organizations, anti-war outfits, and many others. The last iteration of this evolution was Public Media Center, where Mander worked for many years. His last perch was the International Forum on Globalization, which did battle with international trade organizations and treaties, namely NAFTA and the World Trade Organization. It is still going strong.

As an advocate for environmental sanity or other worthy causes, your positions and policies may be sound, rock-solid, but if you can’t communicate them clearly to the public and government officials and agencies, you are stymied. Mander’s genius was precisely this ability: clear, straightforward, compelling communication. And I’m not talking about slogans. Many of Mander’s ads were long, far longer than was thought wise by advertising professionals. But every sentence counted. As Gossage and Mander would say, you can’t afford to have a single dull sentence because you’ll lose your reader. And keep it light and occasionally amusing.

In September 2022, Synergetic Press published 70 Ads to Save the World, An Illustrated Memoir of Social Change by Jerry Mander, a fine and fitting capstone to a remarkable life.

The Magazine of The Sierra Club

The Magazine of The Sierra Club