Adventuring After Spinal Cord Injury

Inside one outdoorsman’s quest for improved access to nature for adventurers with disabilities

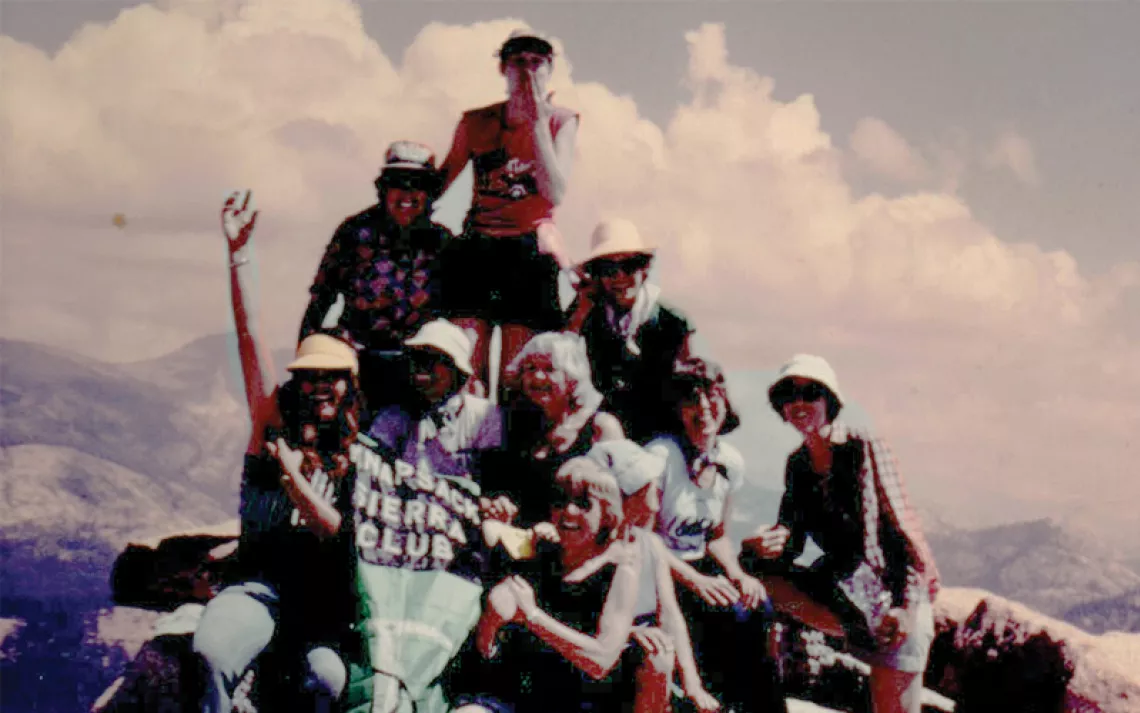

From last September's adaptive camping weekend at Milo McIver State Park in Oregon. | Photos courtesy of West Livaudais

West Livaudais has a hiking resume that measures up with the best of them. Filled with the iconic trails and summits of the Pacific Northwest, it’s an impressive Rolodex of backcountry adventures and lived experiences.

There’s the time he finished the Timberline Trail around Mt. Hood in a single day, blisters and all; the morning he watched the sunrise at "lunch counter" and summited Mt. Adams; and the afternoon he went snowshoeing in Mt. Rainier National Park and spent three hours building an ice cave, only to have it collapse right before dusk. That night, he chased down his dinner with some whiskey.

“The outdoors was my oyster. I could go anywhere,” he says. “I could do anything, as long as I planned and I was prepared.”

Then something happened that he wasn’t prepared for. During surgery to repair a broken hip he suffered in a car accident, Livaudais developed an infection in his central nervous system. Ten days after being admitted to the hospital, he woke up in the ICU, paralyzed from the chest down.

In the months and years that followed, Livaudais was forced to confront a radically new way of life as he adapted to a wheelchair. Like many in this position, he questioned why something like this had happened, while enduring bouts of depression and social isolation. Even simple daily stresses would send him wobbling toward existential dilemma.

“Oftentimes, people living with many different kinds of trauma, their nose is just above the water,” he says, equating his recovery to being stuck beneath a canoe. “So when a wave comes by, they’re gasping for air because that wave is washing over their nose.”

To cope with the circumstances, Livaudais channeled his fear into building a community. In 2015, he founded the Oregon Spinal Cord Injury Connection, a network-based support group for individuals living with similar disabilities around the Pacific Northwest. Many of these people, he soon realized, were fellow former hikers and athletes, and like himself, most of them hadn’t been back into nature since their injuries.

“It really sucks to not be able to get down to the water or not be able to go to a campground and find a raised camping platform,” he says. “It’s quite a fall from grace.”

Physical barriers—like uneven trails, low curb cuts, and inadequate ramps into and out of the water—often discourage people with disabilities from visiting their local parks and natural spaces. And unfortunately, the challenges don’t always end there. Many shelters, bathrooms, and parking lots were constructed before the Americans with Disabilities Act (ADA) became law and, despite continued efforts to retrofit and update areas of concern, remain in need of accessibility upgrades.

“Fundamentally, the parks systems—city parks, municipal parks, state parks—need to upgrade their infrastructure,” Livaudais says. If people don’t know if they can access a trail system, he notes, they’re probably not going to make the effort to visit.

Which is why, in early 2018, Livaudais began lobbying various outdoor advocates, state legislators, and politicians from around Oregon, including first gentleman Dan Little, to forward his agenda of creating a more inclusive parks system.

“It’s for people not only with disabilities, but other communities that have been historically excluded or not included in the planning of outdoors,” he says. “If they can’t get to these public lands that state taxpayer dollars have funded, then fundamentally there’s inequity there.”

This past September, Livaudais’s hard work started to pay off. After a series of successful meetings with park rangers and officials from the Oregon Parks and Recreation Department, he launched the state’s first program for people living with disabilities: an adaptive camping weekend at Milo McIver State Park.

With funding from the Oregon State Parks Foundation, Health Share of Oregon, and the specialty outfitter Adventures Without Limits (AWL), this two-day event brought together a diverse group of 10 campers and their families, all eager to challenge themselves and reconnect with the outdoors.

With funding from the Oregon State Parks Foundation, Health Share of Oregon, and the specialty outfitter Adventures Without Limits (AWL), this two-day event brought together a diverse group of 10 campers and their families, all eager to challenge themselves and reconnect with the outdoors.

“Outdoor enthusiasm is alive and well in the disability community,” says Livaudais, who’s recently been able to enjoy the outdoors with his friends for the first time in years. “But it’s rarer to see a person in a wheelchair in nature than it is to see certain wildlife.”

Prior to the weekend, the campground’s infrastructure was thoroughly overhauled. That included the installation of an electric wheelchair charging system, an improved bathroom changing area, and the leveling of gravel around the park. The group was also provided with a larger campsite that could accommodate multiple wheelchairs around its fire pit and picnic benches.

Making these accommodations was key to the participants feeling comfortable in the environment, according to Helena Kesch, ADA coordinator with the Oregon Parks and Recreation Department. “We sat in a circle around the campfire, and I asked people how the event went and heard directly from them that they loved it,” she reports. “It was exciting to be involved in a camping experience where they felt safe.”

Some of the weekend’s programming also included kayaking down the Clackamas River—a dynamic shared experience for everyone. Jennifer Wilde, director of outreach and development for AWL, assisted with the logistics of amassing adaptive equipment and made sure each participant felt confident in their vessel. “When we are paddling,” she says, “we are all experiencing the water from the same perspective, in the seat of a kayak, and utilizing the same tools to propel ourselves forward.”

Some of the weekend’s programming also included kayaking down the Clackamas River—a dynamic shared experience for everyone. Jennifer Wilde, director of outreach and development for AWL, assisted with the logistics of amassing adaptive equipment and made sure each participant felt confident in their vessel. “When we are paddling,” she says, “we are all experiencing the water from the same perspective, in the seat of a kayak, and utilizing the same tools to propel ourselves forward.”

Though some improvements to the park may have been temporary, the lasting impact of this weekend extended beyond just those two days. This summer, Oregon State Parks and Recreation will host a camping event at Champoeg State Heritage Area for children with learning and developmental disabilities.

Kesch also plans to further her outreach into the disability community for employment and volunteer opportunities and to create an ambassadors program wherein people with mobility challenges can help scout and identify existing problems within the parks. “I’m in this position where I can open up an opportunity to view things with a different perspective and help a community really achieve the utmost outdoor recreation experience that they want,” she says.

For Livaudais, the work’s only just begun. Last month, he premiered a film at the Keen Garage in downtown Portland that was shot during the adaptive camping weekend. The screening helped to secure additional funding for another season of outdoor events and, he hopes, encouraged others to get back into nature.

As for Livaudais’s personal goals? “I’m looking forward to being able to be outside and not have to sweat the logistics.”

Maybe then, he’ll get to add a few more adventure achievements to that resume of his.

The Magazine of The Sierra Club

The Magazine of The Sierra Club