This Boston Start-up Has a Recipe for Low-Carbon Cement

And a massive grant from the Department of Energy to soon produce it at an industrial scale

Sublime Systems cofounder and CEO Leah Ellis (left) watches as scientist Summer Camerlo-Bass scoops cement from a mixer. | Photos by Ken Richardson

This past June in downtown Boston, a building with an uncanny lobby was nearing the end of construction. A bronze-lettered plaque embedded in a slab of concrete flooring near the entrance read, “This floor is the first commercial use of Sublime Cement made with a fossil-fuel-free cement manufacturing process. A step on this floor is a step closer to our post-carbon future.” Making cement—which, mixed with water, binds sand and gravel to form concrete—is normally a carbon emissions nightmare. The process used to make the material in these new slabs, created in Sublime Systems’ pilot plant just four miles away in Somerville, Massachusetts, is the first in the world to avoid that.

The presence of concrete in our environment “is so big that it’s invisible. It’s like the air you breathe,” said Leah Ellis, Sublime’s CEO and cofounder, during a conversation at the plant a month earlier. Since she and Yet-Ming Chiang started the company in 2020, teams of scientists have honed how to make cement more sustainable—recently by using electrochemistry to break down calcium silicate, instead of burning fossil fuels to break down limestone.

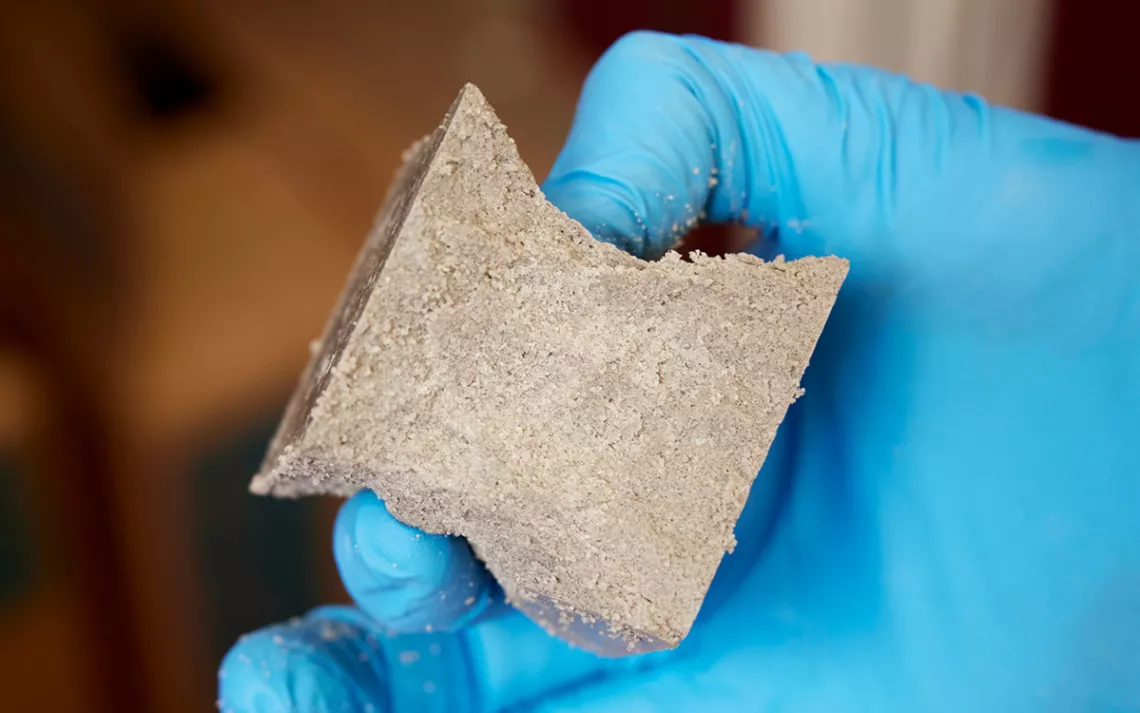

Decarbonized cement is tamped into molds.

Portland cement has been the industry standard building material since the late 1800s, and its core material has always been lime. To make it, manufacturers heat limestone in 2,500°F kilns. The firing process emits carbon dioxide, and the byproduct of heated limestone is also carbon dioxide. At least 8 percent of global emissions now come from cement production; for comparison, aviation’s share is 2 percent. Decarbonizing this industry will have an outsize benefit on emissions reductions.

There are about a half dozen other companies in the cement decarbonization game, but all are at the lab stage. Sublime has found a way to fully decarbonize the process of making cement, which, along with having a commercial client, puts it at the front of this industrial shift. And its cement still passes all the same standard tests as Portland cement. “Same strength, set time, flow, durability,” said Ellis—without the dubious use of carbon capture and sequestration.

Ellis is a chemistry nerd, a trained battery scientist who interned at Tesla, and a former resident of a hippie commune. When she talked about the science of using electricity to transform one solid material into another, she called it “magic,” and her eyes widened behind her pink plastic frames, even though this woman with a PhD knows exactly what’s going on.

At Sublime’s pilot plant in Massachusetts, technicians manufacture and test small quantities of cement.

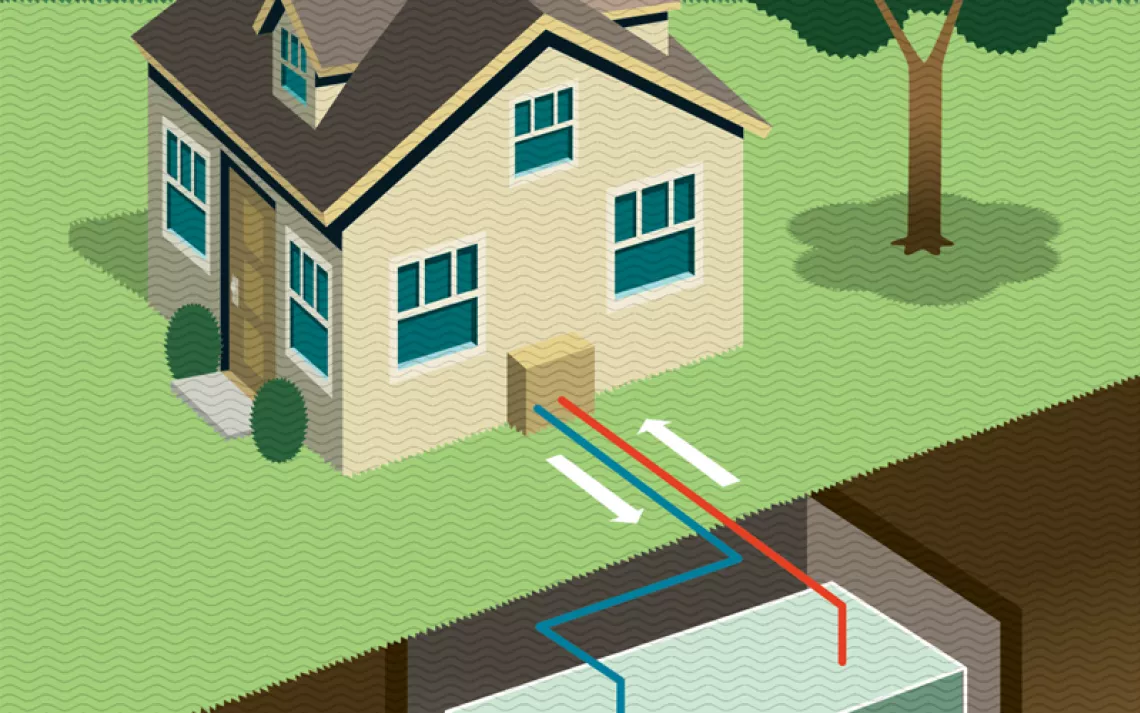

In Sublime’s pilot plant, technicians manufacture small quantities of cement bound for its earliest commercial uses, such as the flat slabs at the site downtown. As the company scales up, its cement may be bound for additional uses—say, concrete support beams—so scientists continue with research and development. The plant they work in looks and smells as familiar as any old suburban Home Depot. On the warehouse floor, adjustable red metal shelves hold rows of work boots and tools, and stacks of brightly colored five-gallon plastic buckets reach six or seven feet high. Next to one stack sits a miniature concrete mixer covered in gray splatters. In a small, enclosed area, the research and development team blurs the line between baking and advanced materials science as it tries to perfect the process for making mortar (a hardened form of cement).

The recipe: Scoop and weigh a powdery form of Sublime’s carbon-free cement in a bowl. Measure and add water. In an electric stand mixer, stir to combine for 30 seconds. With the mixer still running, slowly add sand. Combine for another 30 seconds. (In the company’s earliest days, its scientists used an actual KitchenAid mixer for this.)

In May, scientists Summer Camerlo-Bass and Michael Sheahan were testing if they could change the flow of Sublime’s cement without impacting the strength. They poured some of the mixture onto a metal disc that lifted up slowly then abruptly bounced up and down, forcing the mixture to spread out into a pancake. They next used a silicone spatula to scoop some of the gloop into nine cubic molds resembling muffin tins, then meticulously tamped the surface of the filling to distribute it. To test cubes of cement from previous batches that had dried for three, seven, and 28 days, they placed them under the pressure of a mechanized fist and crushed them.

Sign up to receive Sierra News & Views

Get articles like this one sent directly to your inbox weekly.

With this action you affirm you want to receive Sierra Club communications and may vote on policy designated by the Sierra Club Board.

“You couldn’t imagine how specific some of these test methods are for cement,” Sheahan said. “You would think it’s just cement. It just works.”

At Sublime’s pilot plant in Massachusetts, technicians manufacture and test small quantities of cement.

The reinvention of cement is a new industry without an obvious career pipeline. Camerlo-Bass came to Sublime straight after graduate school, in search of a path opposite that of her classmates. “I went to an engineering school where, like, 50 percent of my friends went to either Lockheed Martin or the petroleum industry,” she said. “I wanted to do something that I felt a little bit better about.”

The reason Sublime doesn’t have more commercial clients yet—and why that one job downtown was limited to three concrete slabs in the building’s lobby and a few feet of sidewalk outside—is not because of a lack of interest but because the company does not currently have the production space to fulfill more jobs. That’s about to change. In 2026, Sublime will open a commercial-scale plant in Holyoke, using a grant it received in March from the Department of Energy for up to $87 million. There, it will begin producing tens of thousands of tons of cement annually. Ellis wants people to stop and consider carbon-free cement in their environments, unlike the billions of tons of cement already on Earth that go virtually unnoticed.

The shape of this cement mortar shows Sublime’s material performed as expected during a strength test.

“When people think of clean tech, they think of wind turbines and solar panels and EVs—and I also want people to think about cement,” she said. “I think people like being made aware of things that were invisible to them.”

When the building in downtown Boston opens to office workers, they just might notice a difference in the cement, even without the plaque. Where Sublime’s modest slabs meet the expanse of concrete made with Portland cement in the rest of the lobby, there’s a stark color difference. Because Sublime doesn’t burn dirty fuels to make cement, its finished concrete is a lighter shade of gray—cleaner, even, to the naked eye.

The Future of Cement

A Quiet Force

Sublime Systems’ pilot plant is nestled in a residential neighborhood. Absent dangerously hot kilns and asthma-causing gases, it’s safe for locals to sip craft lagers at a neighborhood brewery on the other side of a shared wall.

Industrial Revolution 2.0

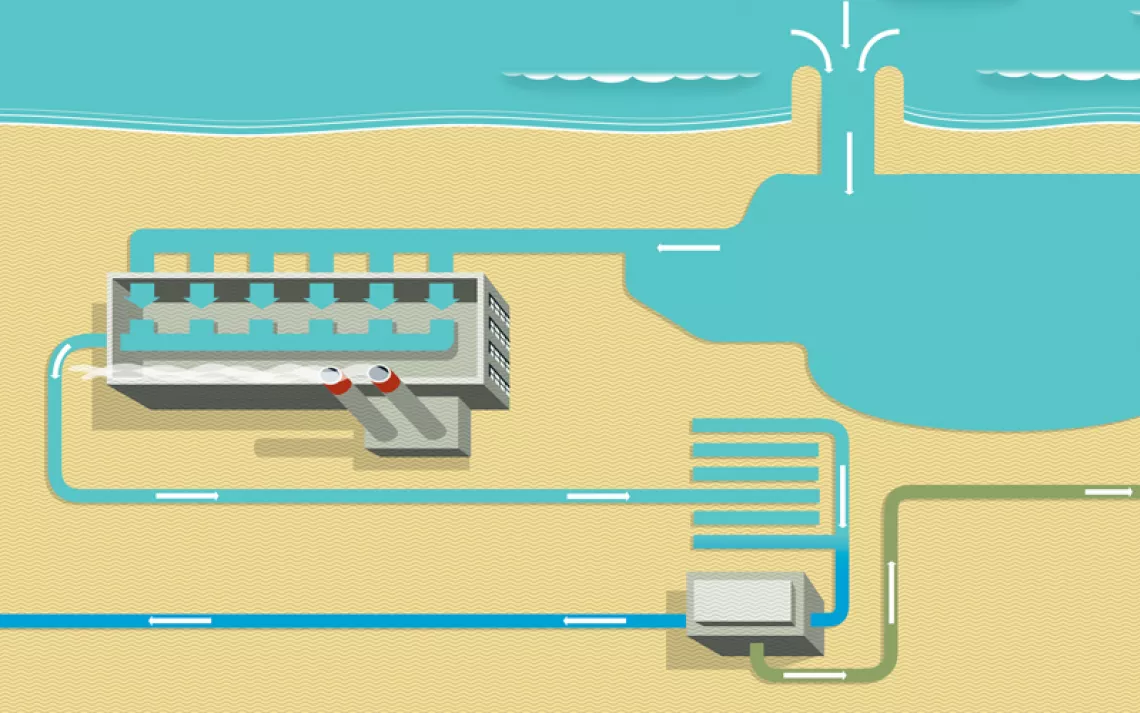

Sublime’s upcoming hydroelectric-powered, commercial-scale plant will take over the site of a former paper mill in Holyoke. During the industrial era, this historic town made 80 percent of the writing paper in the US. In this century, it will host part of the electrification revolution in manufacturing.

Concrete Jungle

Humans make 30 billion tons of cement every year, and the total mass of concrete on Earth is poised to exceed that of all living matter in about 15 years. Look for concrete on a walk, sitting in your house, driving to work—it’s everywhere. You won’t be able to unsee it once you notice it.

The Magazine of The Sierra Club

The Magazine of The Sierra Club