What Would It Take to Bring Renewable, Reliable Power to Puerto Rico?

The island is struggling to build a more stable electrical grid. What’s taking so long?

People walk through San Juan during a power outage.

ONE NIGHT in November 2023, a few minutes before 9 p.m., three neighborhoods went dark in San Juan, Puerto Rico. No television for watching the game or internet for keeping up with friends. No air conditioning to take the stick off a humid night. The routine sounds of city life ceased, and an eerie quiet settled in.

Blackouts like this are common in Puerto Rico. Power is typically restored in a few hours, but sometimes the outages can last for days. Darkened traffic lights force people to treat multilane intersections like four-way stops, and there is no power to pump water into homes. Fifteen minutes of pounding rain can shake the feeble electrical wires enough to cause a local outage. Backup generators are costly and unrealistic in working-class neighborhoods. For a reporter passing through last fall, the blackout inconvenience was temporary: a hot night when the refrigerator wouldn’t keep a yogurt cold until morning. But for Puerto Ricans, it’s a routine reality—one that those on the US mainland can hardly imagine.

Puerto Rico stands at the center of two intersecting crises. Climate change is warming ocean temperatures to the point where hurricanes regularly hammer the island and its aging infrastructure. In 2017, Hurricane Maria left 200,000 families powerless for more than six months. Meanwhile, an old and poorly maintained energy grid largely built on fossil fuels is gradually falling apart after years of derelict management by the island’s former grid operator, the Puerto Rico Electric Power Authority (PREPA).

Solar panels are installed on the rooftops of several businesses around the town square in Adjuntas, Puerto Rico.

Since Maria struck the US territory, a concerted effort to boost the island’s energy resilience has been underway. In 2023, the US Department of Energy (DOE) announced the Puerto Rico Energy Resilience Fund, a $1 billion pot to be divvied up among projects mostly focused on rooftop solar installations. Coal-fired generation is slated to end by 2028. And in February, the DOE released the results of PR100, a two-year study to assess how the island can reach 100 percent renewable energy by 2050. “There’s this huge federal clamor for this transformation,” said Ruth Santiago, a local environmental lawyer and a member of both the White House Environmental Justice Advisory Council and the executive board of the Sierra Club’s Puerto Rico Chapter. “[Policymakers] know that in the next hurricane, the towers, the poles, the transmission and distribution lines will be torn down.”

On the ground, the renewable energy transition is not straightforward. Many of the 117,000 existing rooftop solar and storage systems in Puerto Rico were installed by people who can afford it. For everybody else, government programs and nonprofits are stepping in, providing the groundwork for equitable solutions like community-scale microgrids and solar-energy cooperatives.

The goal? Renewable, decentralized power.

POWER OUTAGES—not just the extreme storms that cause them—can be lethal.

When Hurricane Maria slammed into Puerto Rico in September 2017 as a Category 4 storm, it caused the longest blackout in US history. Around 3,000 people died. An estimated 64 deaths were linked directly to the storm; the majority of deaths resulted from power outages in the aftermath. Puerto Rico’s grid was in desperate need of improvement even before Maria—the storm made the grid’s fractures blatantly obvious. Transmission lines running across the island’s mountainous forest regions were poorly maintained and weighed down by overgrowth. The lines also run from north to south, and hurricanes cross the island from east to west, inevitably taking them down. When Maria hit, most of those lines were destroyed, preventing electricity from reaching hospitals and homes. The poorest and most vulnerable households, dubbed “last mile communities,” were the last to have electricity restored.

“Some people are going to make money, and then they make it look like they’re doing us a favor because they

will help us transition to solar.”

Community organizers thought the disaster would catalyze a true rebuilding of Puerto Rico’s old and mismanaged grid. “At the time, everybody thought, ‘This is it. This is the opportunity,’ ” recalled Elvia Melendez-Ackerman, a plant ecologist at the University of Puerto Rico, Río Piedras. “To us, that was like a historic moment. The government would finally understand.” This was the time, they thought, to move away from centralized fossil fuels and toward distributed energy—producing small amounts of electricity at many sites as close to the end user as possible. Buildings would use renewable energy to create their own electricity.

But it still hasn’t happened. In September 2022, nearly five years to the day after Maria hit, Hurricane Fiona grazed the island as a comparatively weak Category 1 storm. Because of the island’s frail grid, it caused a weeks-long blackout for over a million Puerto Ricans. An estimated two dozen people died. “Years later, I don’t think the government understood,” Melendez-Ackerman said. “There were other forces at play.”

Wanda J. Ríos Colorado advocates for energy upgrades and climate resilience in her community of La Margarita in Salinas.

She was referring to a public-private partnership that has run the island’s energy system for years, with a decidedly corporate incentive: making a profit. In 2017, after accumulating $74 billion in debt, Puerto Rico filed for the largest municipal bankruptcy in US history. Of that debt, nearly $10 billion was held by PREPA, which could not pay back its creditors and bondholders. The government’s plan to ensure PREPA did not incur further debt was to privatize the island’s energy system. In 2021, under the administration of Governor Pedro R. Pierluisi, Puerto Rico entered a 15-year, $1.5 billion contract with Luma Energy—a privately owned utility—to improve and operate the PREPA-owned grid. Boosters of this arrangement promised that it would save ratepayers money and improve the grid’s infrastructure, but those promises turned out to be an illusion.

Luma, a Canadian and American venture, promptly fired the majority of PREPA’s workforce—and with it, the institutional knowledge of how to run the antiquated grid. That same year, the island experienced seven times more blackouts than the total number in all 50 states. Then, in 2023, the government issued a new contract to another private company—Genera PR, a subsidiary of New Fortress Energy, a New York–based fossil fuel company—to take over energy-generation responsibilities from PREPA.

Critics of the privatization say power is nearly as unreliable now as it was during the aftermath of past hurricanes. One reason, according to Jordan Luebkemann, a senior associate attorney for Earthjustice, is that private companies aren’t beholden to voters; they’re beholden to profit. “A private utility isn’t really accountable to anybody except for whatever independent regulator is independently regulating it,” he said. The Puerto Rico Energy Bureau, he added, has regulated these entities weakly, if at all.

The arrangement has left Puerto Ricans deep in the red. Plans to restructure and pay off PREPA’s debt threaten to offload the burden onto ordinary people in the form of higher electricity costs. For some energy leasing companies on the island, the privatized model for centralized energy has become another grift, concentrating profits while socializing the costs of maintaining an unreliable grid largely driven by polluting fossil fuels.

For a growing number of Puerto Ricans, the sun holds a clear answer to the crisis.

IN PUERTO RICO, the flag one flies is an expression of political identity. A house displaying the territory’s royal-blue flag alongside an American flag demonstrates support for the island’s current relationship with the United States. A solo American flag signals preference for statehood. A light-blue version of the Puerto Rican flag is a call for total independence from the US. In Adjuntas, a small municipality just northwest of Ponce, a unique flag flies above several buildings: a yellow sun on a green-and-blue background.

The highways become steep and winding the closer you get to Adjuntas. It’s hard to imagine large trucks towing wide photovoltaic panels through the fog on these narrow mountainside roads. Yet sprawling purple-blue panels adorn hundreds of the rooftops there, turning sunshine into power. At the very end of Calle Rodulfo González, before the road takes a sharp turn around a bend, a solar-powered microgrid offers a new way forward for the rest of the island.

The coffee is served fresh at Casa Pueblo, a community nonprofit that sustains itself partly with sales of its self-grown and roasted beans. The organization came from humble beginnings. In 1980, environmental-justice activists Alexis Massol and Tinti Deyá led a movement opposing plans for open-pit copper mines across the island, which had been endorsed by the US government. The mines would have destroyed the lush, green forests blanketing the mountainsides and contaminated watersheds with toxic sediments if not for their efforts.

By 1999, “we realized that the greatest threat to natural-resource conservation was the energy agenda,” said their son, Arturo Massol-Deyá. If Puerto Ricans could find a way to produce their own energy, it would make them less dependent on the United States. “For us, energy is a means to promote an alternative model for local development,” he said. “In order to achieve that, we have to democratize energy generation.

We decided to break up the fossil fuel dependency.”

In the years since, the family-led team grew, and with it, the community’s microgrids. “It’s also about people controlling the infrastructure for power generation,” Massol-Deyá said.

Puerto Rico has the second-most expensive residential electricity rates in the United States, behind Hawai‘i’s, at about 22 cents per kilowatt-hour. Rates in the rest of the US average just 17 cents, even though the US median household income is over three times that of Puerto Rico. Rooftop solar and microgrids are more affordable on the island in the long run. With the island’s year-round sunny weather, individual solar panels with storage allow people to generate their own electricity. And unlike California and Hawai‘i, whose state governments have walked back incentives for rooftop solar, Puerto Rico is fighting to keep its net metering program. This way, consumers can continue to earn credits from Luma for supplying the grid with excess power from their solar panels.

High-voltage power lines in southern Puerto Rico are vulnerable during storms.

“We are building an alternative country inside a colonial country,” Alexis Massol said over rice and chicken at Restaurante Vista al Río, a riverside spot running on solar panels installed by Casa Pueblo. “This is a new way of self-determination. We are making changes every day. We don’t have to wait for four years.”

There’s plenty of opportunity for the type of decentralized rooftop solar that advocates have been asking for, said Marcel Castro-Sitiriche, an electrical engineering professor at the University of Puerto Rico, Mayagüez. In addition to the $1 billion allocated for rooftop solar through the DOE’s Energy Resilience Fund, there is more than $70 billion available through FEMA and other agencies. “There’s enough funds, but they’re not channeled to address this,” he said. For example, a 2018 Hurricane Maria recovery plan proposed up to $6 billion specifically for solar-powered generators.

Funding isn’t the problem so much as implementation. Queremos Sol (“We Want Sun”), a diverse alliance of nonprofit, community, utility, and academic groups, and its facilitating nonprofit, Cambio PR, showed how feasible it would be to apply funds to rooftop solar installations across the island. (The Sierra Club was one of the founding members of the alliance.) In 2021, Queremos Sol published a report showing that transitioning to 75 percent distributed generation over 15 years would drastically cut the imports of fossil fuels while supplying enough energy and scrapping the need for new fossil fuel generation. The report also suggested that it would only take $650 million to update the grid to support this type of transition—far less than what’s been allocated.

Puerto Rico now has more than $14 billion in federal funds to transform its outdated grid. If that money were used toward the type of transition Queremos Sol proposed, it “would not only reduce vulnerabilities across the island and provide 100 percent resiliency to homes, but it would also stabilize our electric bills,” said Ingrid Vila Biaggi, an environmental engineer and Cambio’s cofounder. “What we’re missing is pretty much political will.”

JUST SOUTHEAST of Adjuntas is another glimpse of Puerto Rico’s energy future. In La Margarita, a small neighborhood of just over 300 homes in the town of Salinas, one woman is on a mission to make her community more energy resilient.

After Hurricane Maria, Wanda J. Ríos Colorado’s family didn’t have power for two and a half months. When it grew unbearable, they flew to Florida for 10 days just to shower, sleep, and feel like “normal people” again. “It was terrible,” she recalled. “I didn’t know how long it was going to be without any power.”

Ríos Colorado has lived in La Margarita since she was a teenager—save for the few years she spent serving in the US military. She eventually bought her own house next door to her mother’s. She runs a small laundromat with her daughter but spends most of her time advocating for energy upgrades and climate resilience. Ríos Colorado is now running for mayor. “Solar Salinas” is the centerpiece of her platform: a vision of a place where microgrids support everyone’s electricity needs and there is less fear of being powerless during storms.

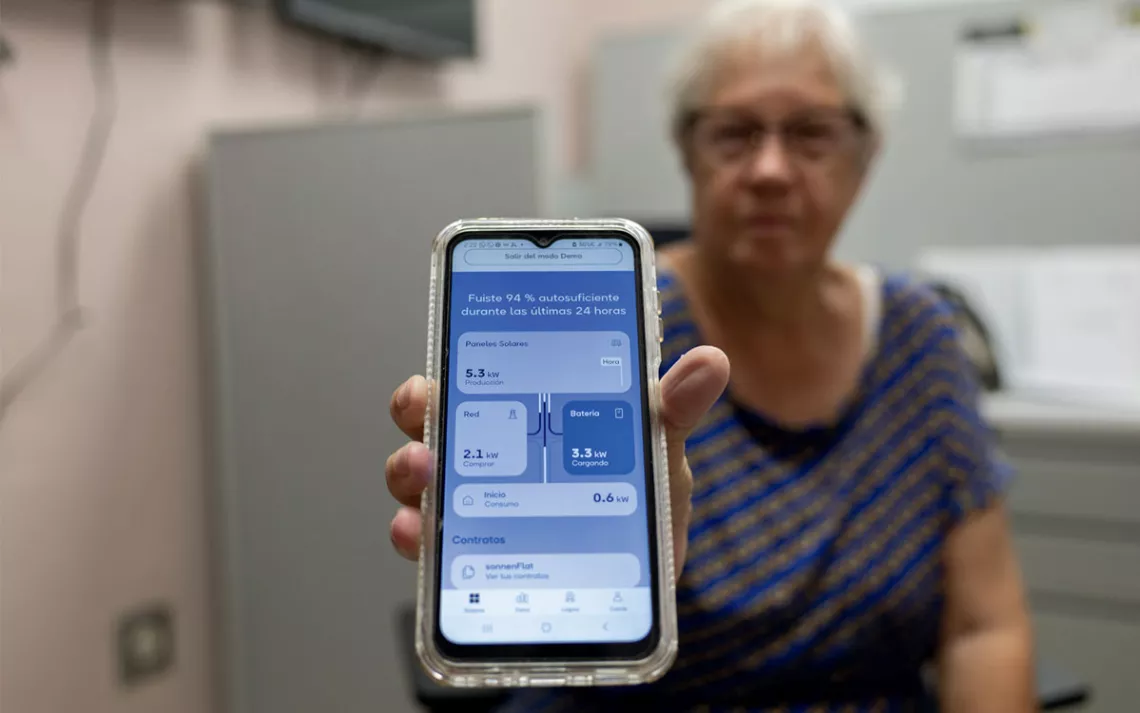

Elsa Modesto, a resident of La Margarita, uses a phone app to track her home solar electricity consumption.

Low-lying La Margarita is prone to flooding and has a high elderly population. Because the electrical wires run underground, residents easily lose power when there’s heavy rain. It’s a major health and safety concern for those who depend on refrigerated medications, use home medical devices, and are vulnerable to hurting themselves in slippery, muddy conditions when it floods. Even without heavy rain, residents lose power about once a week for two to three hours, Ríos Colorado said. Sometimes the power is out for longer. And often, there are power surges, frying kitchen appliances or dimming lightbulbs.

So, Ríos Colorado and other community members established a solar cooperative, a way for people to collectively bargain and pay for rooftop solar and storage at discounted rates. The nonprofit Solar United Neighbors has also helped by identifying loan programs and assisting rooftop-solar buyers through the contract process. In the end, cooperatives allow communities to own and operate their own microgrids for a lower cost.

Meanwhile, La Margarita has received federal funds to help pay for solar installations. In February 2023, Secretary of Energy Jennifer Granholm chose the community as one of 10 recipients of the DOE’s Community Clean Energy Coalition Prize.

A few dozen houses and traffic lights are now part of La Margarita’s budding microgrid, with some residents paying only $4 a month thanks to net metering. By contrast, customers leasing a system from companies like Sunnova Energy are locked into a minimum monthly payment of $145—even if they use less energy than their bill suggests. If La Margarita can form a complete microgrid, customers would pay closer to $30 a month, Ríos Colorado estimated. The idea is for other neighborhoods in Salinas to transition to a microgrid model, prioritizing people who require medical equipment, use food stamps, and support other family members. “Those are the ones that need us,” she said. “With this system, we won’t have any trouble with the next hurricane.”

WHEN THE DOE released its PR100 study in February, it immediately sparked controversy—even among its coauthors. While the report championed renewable energy, some of the study’s contributors disagreed with the recommendations. The report proposed that the largest slice of renewable energy would come from utility-scale solar farms. It’s a worrisome proposition to some people on the island.

Utility-scale solar installations are usually sited on large, flat areas. In Puerto Rico, flat land runs along the perimeter of the island, where most of the suitable land for agriculture is located. Constructing solar farms in those locations would mean destroying land that would otherwise be used for growing food, while creating erosion that contributes to flooding. Although the DOE said these solar farms would avoid agricultural lands, existing utility-scale solar and wind farms have taken up fertile acres—a serious concern considering that Puerto Rico already imports more than 85 percent of its food. Placing solar farms atop industrial complexes or parking lots, some have suggested, would help avoid this issue.

Solar farms are also less cost-effective than rooftop solar at the ratepayer level. Because of Puerto Rico’s high retail electricity rates, taking advantage of net metering through rooftop solar saves ratepayers money. Relying on solar farms could prevent residents from adopting rooftop solar, said Castro-Sitiriche, who has pushed for decentralization. With the government’s proposed scenario—which is the only way the DOE can meet its 40 percent renewable energy goal by next year, he noted—solar farms will lock customers into a high, set rate for two decades. To go from centralized fossil fuels to centralized solar farms leaves the same people in power, Castro-Sitiriche argued. “Some people are going to make money, and then they make it look like they’re doing us a favor because they will help us transition to solar.”

As part of its Energy Resilience Fund, the DOE announced $440 million for companies and nonprofits to install rooftop solar for tens of thousands of low-income households, such as those in La Margarita. Yet most of that money isn’t going directly to community leaders like Ríos Colorado. Instead, it’s largely allocated to big companies such as Sunnova and Sunrun.

Even the DOE’s small-scale funding efforts come with drawbacks. “It’s sort of under the guise of community involvement, but that’s not really it,” Lorena Vélez Miranda, an attorney for Earthjustice and a Puerto Rico native, said. While the money is helpful, the decision to fund US-based corporations mirrors a decades-old pattern. “It’s this colonialism that infiltrates all aspects, including energy,” she said. “It’s frustrating for the people here to see that they thought that this was a big opportunity for improvement, and it’s the same. We’re still working with these big companies. . . . We’re still reliant upon someone else.”

Despite the $23 billion the DOE allocated for long-term rebuilding after recent natural disasters in Puerto Rico, only $1.8 billion has been spent, according to a February report from the Government Accountability Office. The grid is one of the most complicated pieces of the recovery, said Christopher Currie, a GAO director focused on emergency management. He compared the island’s grid upgrades to modernizing some parts of an old car without replacing the engine. The DOE, FEMA, and other agencies each have their own programs that are trying to address the island’s grid failures—an uncoordinated effort that has stalled the process.

“Federal disaster-recovery programs are so fragmented, and they’re sort of disjointed and not harmonized to work well together,” Currie said. “That’s a bigger problem nationwide that we’re trying to fix. What you see is the worst-case scenario in Puerto Rico on display.”

On a Saturday morning in Adjuntas, the town square buzzed with people. Abuelos lounged in plastic chairs outside their favorite convenience store, smoking cigarettes and telling jokes. Neighbors fired up the grill for an afternoon barbecue.

Adjuntas represents a small pocket of energy resilience. With Puerto Rico’s glacially slow grid updates, what could a decentralized power system look like across the entire island?

For organizations like Casa Pueblo, Queremos Sol, and Solar United Neighbors, that picture is clear: rooftop solar systems connected to local microgrids that serve everyday needs for everyday people. That system need not involve huge corporate energy companies driven by a singular motive to turn a profit.

Introducing distributed generation to a centralized grid—creating a two-way electricity flow between power generators and people’s homes—requires new connections to the grid. There still needs to be a utility to maintain the wires, which inevitably comes at a monthly cost to rooftop-solar owners. But experts agree that achieving grid stability using solar energy is possible in tropical Puerto Rico, where days are roughly the same length all year and sunshine is plentiful.

To many, the quest for clean energy in Puerto Rico is so much more. “Clean, not only from CO2 emissions,” Castro-Sitiriche said, “but clean from imperialism, clean from colonialism, clean from oppression, and clean from corruption.”

The Magazine of The Sierra Club

The Magazine of The Sierra Club