The High-Tech Tools That Can Bust Careless Oil and Gas Drillers

Satellites can now detect invisible methane leaking from wells, telling crews on the ground where to plug the leaks

Pumps hissed, a camera oscillated, and wind whistled through oil and gas wells at the Methane Emissions Technology Evaluation Center at Colorado State University. The mechanical symphony could be the soundtrack to a revolution in our ability to detect and measure methane, the invisible, odorless “super pollutant” responsible for a third of global greenhouse gas emissions.

The United States is the world’s largest producer of oil and gas and its biggest emitter of methane—much of it leaks from oil and gas operations. A raft of new federal and state laws require energy companies to monitor and fix emission leaks. That’s why companies are lining up to test methane-detection devices at the Fort Collins facility.

“Things are moving quickly—people have realized legislators aren’t messing around,” said Ryan Brouwer, facility manager at the testing center. “We have 12 different companies testing now. I am booked until the fall, and we have a waiting list.”

Brouwer showed off high-pressure tanks that feed gas into wells, other tanks, and separators. Their valves, pipe joints, and other fittings leak the methane—the main component of “natural gas”—into the air. Then finely tuned handheld sensors, softball-size devices mounted on hefty tripods, and equipment attached to drones and aircraft go to work. These sensors report their readings of the rate, location, and duration of leaks to center scientists, who then compare them with data on the known releases.

Why all the fuss? Because methane is an enormously powerful greenhouse gas, 80 times as potent as carbon dioxide at trapping heat. As an article from the Rocky Mountain Institute put it, “If CO2 pollution wraps one blanket around the earth, methane pollution is like wrapping the earth in over 80 blankets.” Studies show that eliminating these emissions would lead to immediate benefits for the climate and public health.

The concentration of methane in the atmosphere today is two-and-a-half times preindustrial levels, and accelerating. Agriculture is the largest anthropogenic source (all those belching cows, mostly), followed by oil, coal, gas, and bioenergy, which account for 46 percent of emissions. Rotting organic material in landfills is another major contributor.

Of these offenders, the emissions from fossil fuels are perhaps the easiest to deal with, as it’s largely a matter of plugging leaks. According to the International Energy Agency, methane emissions from fossil fuels must drop by three-quarters this decade to meet the Paris Agreement climate goals. Hence the race at the Colorado State center to develop and improve methane-detecting sensors on the ground and in the air. As these technologies improve, scientific studies are finding that earlier calculations widely underestimated the actual amount of the gas in the atmosphere.

“We saw so much variability in methane emissions across the regions,” said Evan Sherwin, who led research at Stanford University for a paper published in Nature in March. “If we compare our numbers to the Environmental Protection Agency’s numbers, ours were three times higher.”

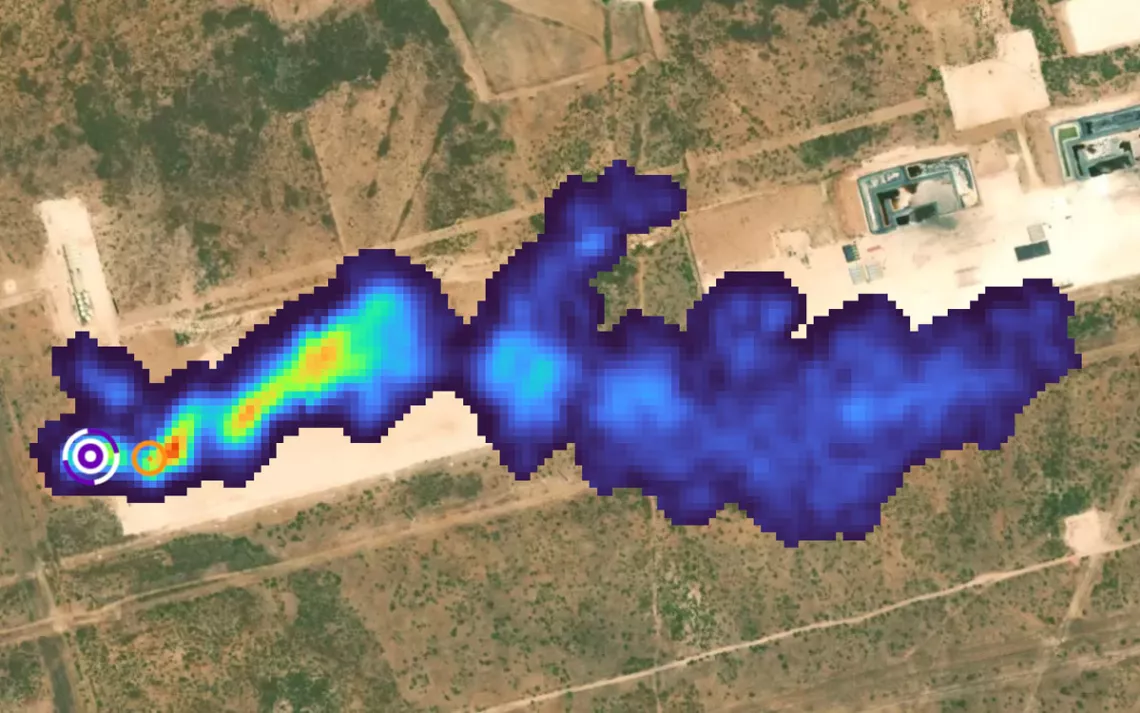

Sherwin worked with a team from Stanford, Kairos Aerospace (now Insight M), and other labs to conduct aerial surveys over six hydrocarbon-producing regions, taking a million measurements over Colorado, Texas, New Mexico, and Pennsylvania. They estimated that the operations emitted 6.2 million tons of methane a year—equivalent to all the CO2 emissions from fossil fuel use in Mexico.

“We found [that] as low as .05 percent of oil and gas production facilities are responsible for half or more of emissions,” said Sherwin, who is now at Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory. “We really do now have the tools to find the bulk of the emissions that matter pretty rapidly.”

In addition to worsening the climate crisis, methane emissions represent an annual loss of $1 billion to the gas companies. The prospect of recovering that leaking gas is incentivizing energy companies worldwide to fix methane leaks discovered by satellites. Six years ago, energy companies in the Oil and Gas Climate Initiative invested in the satellite company GHGSat; they’ve used the satellites to help detect and quantify leaks in Iraq, Algeria, Egypt, and Kazakhstan. After the results were confirmed with on-the-ground testing, local operators fixed the leaks, said Bjørn Otto Sverdrup, chair of OGCI’s executive committee.

“Three problems we discovered were approximately equal to a million tons of carbon dioxide equivalent,” he said. “It’s like taking away close to 250,000 cars.” Methane detection and measurement, he concluded, “is now at a point where we may be able to start moving the needle at scale.” Indeed, data from the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration shows that the methane increase in the atmosphere in 2023 slowed from the record growth earlier this decade. Even so, the year marked the fifth-highest increase since 2007.

More than a dozen satellites now orbit the planet scanning for methane plumes. Some are privately owned; others are operated by governments and nonprofits. Data from select satellites are available on the International Methane Emissions Observatory’s online data portal.

Mark Brownstein is a senior vice president at the Environmental Defense Fund, which developed its own methane-detecting satellite, MethaneSat. “This is data that will provide the most comprehensive amount of emissions and the rate at which they are being emitted,” he said. “We see this data as being incredibly important to hold countries and companies accountable to commitments they’ve made.”

Satellites have limitations though. They can’t see past cloud cover or over water, and they have time constraints on how much data they can collect from any one location. Consequently, said Dan Zimmerle, the director of Colorado State’s methane center, all types of sensors are needed to make progress in fixing leaky oil and gas equipment and spotting flares that fail to fully combust all the gas being vented.

Zimmerle’s operation is set to receive $25 million from the Department of Energy and industry partners to modernize equipment, standardize testing solutions, and support field trials of methane-sensing satellites. The team is searching for locations to test how the satellites are performing.

“We will put up a test release,” Zimmerle said. “They will task on it, we will get a report from them that says what they saw, and we will compare it to the real thing.”

The Magazine of The Sierra Club

The Magazine of The Sierra Club