America's Disappearing Grasslands—and Grassland Birds

For prairie birds, flyover country is an increasingly hostile place

On a June morning, five people are standing in an emerald prairie, staring up at the sky in the Fort Belknap Indian Reservation in north-central Montana.

“See it?” Nancy Raginski asks.

“No,” I say, still trying to focus my eyes amid the world’s most depthless blue. I see only glittering white specks—an optical phenomenon, I’ll later learn, caused by white blood cells rushing across my retina.

“Wait, is that it?” someone asks. “Little brown dot wayyy up there?”

The bird—which I still can’t see—calls. The song is fast and high and strange—a series of whistles, or maybe zooms. It sounds insistent, as if the sky were a door and its bell had just rung six times.

On the ground, Sprague’s pipits are said to be unassuming and secretive, with plain buffy plumage. But in the air, they’re fabulous. Males perform the avian world’s longest aerial mating displays, staying aloft for as long as three hours. Historically, pipit song was a common part of the great songbird orchestra that played every summer throughout the grasslands of North America. When ornithologist Edward Harris visited the prairies in 1843 with John James Audubon, he at first thought the sound was coming from the grass. “We at last looked upward and . . . saw several of these beautiful creatures singing,” Audubon wrote, “in the clear thin air of that country.”

“No other bird-music heard in our land compares with the wonderful strains of this songster,” observed ornithologist Elliott Coues some decades later. “There is something not of this earth in the melody, coming from above, yet from no visible source.”

The central grasslands are now about 40 percent of their size before european settlement.

These days, pipits are increasingly hard to find. That is why Raginski and her three-woman team are hammering rebar into a hillside, erecting a mist net to safely catch them. Raginski is a doctoral student at the University of Georgia, a fellow at the Smithsonian Conservation Biology Institute, and, in her words, “pretty much it” when it comes to scientists studying Sprague’s pipits. (The bird’s name may change in the near future, in keeping with the American Ornithological Society’s new policy of not naming birds after people.) Along with Smithsonian interns Eva Noroski, Mia Murray, and Natalie Miller, Raginski came out this morning to catch a few birds and affix them with radio transmitters.

Twenty minutes after the team finishes setting up, a pipit flies into Raginski’s net. It looks like an American robin wearing all-brown camo but with its own unmistakable demeanor: watchful, dignified, even aristocratic. A large brown eye regards us all.

Raginski gently extends a wing, the feathers fanning out like swatches from the brown section of a paint store. Before releasing the pipit, she measures the white tips of its feathers. They are slightly worn—perhaps by wind and hard traveling. A pipit might live three to five years, Raginski says—flying as many as five round trips up and down the North American continent.

This pipit travels a continent much different from that of its ancestors. Several forces that shaped the prairies—buffalo, prairie dogs, people wielding fire—are now mostly absent. North America’s central grasslands are now less than half the size they once were, and are shrinking. Habitat loss is the biggest reason we’re losing birds, according to John Carlson, regional grassland conservation coordinator for the US Fish and Wildlife Service: “There’s just no place for them to go.”

SINCE 1970, 3 BILLION BIRDS have disappeared from North American skies. Some corners of the avian world are faring worse than others. Grasslands have lost more birds—700 million, more than half their total population—than any other biome has. Since the dawn of the space age, Sprague’s pipit numbers have fallen by 79 percent.

The growing silence on the prairie portends a broader crisis. Biologists often look to bird populations as indicators of the health of ecosystems, and American grassland bird species—including long-billed curlews, mountain plovers, prairie chickens, burrowing owls, aplomado falcons, and a host of songbirds—are in trouble. Ubiquitous pesticide use has made agricultural fields more dangerous: A single neonicotinoid-coated corn seed, for example, can be enough to kill a grasshopper sparrow. “We’re at a tipping point,” Tammy VerCauteren, executive director of the Bird Conservancy of the Rockies, recently told the Society for Range Management. “What we do in the next 10 years will define our central grasslands landscape for generations to come. . . . Will the chorus be there for our grandkids?”

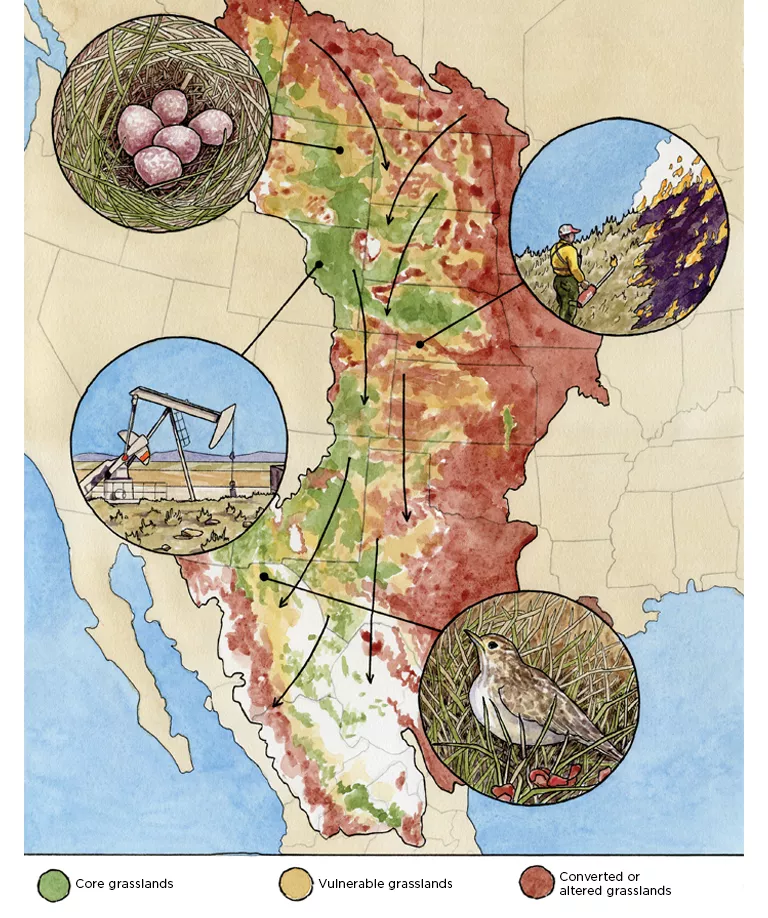

Data provided by Sarah Olimb/World Wildlife Fund

Growing cities and woodlands erase grasslands, but the plow remains the prairie’s greatest enemy. Since 2012, farmers have converted a Louisiana-size chunk of North American grasslands. “I see no material difference in the plowing of a prairie and the felling of a tree in the Amazon,” Marshall Johnson, chief conservation officer at the National Audubon Society, told me. The central grasslands are now about 40 percent of their size before European settlement.

VerCauteren is one among many who don’t intend to let the prairies disappear. Around 2018, she began working with other leaders to start the Central Grasslands Roadmap (CGR), a tri-national effort that convened Native nations; state, provincial, and federal agencies; ranchers; nonprofits; and energy and agricultural companies to work together on grassland conservation. Several agencies and groups that are part of the CGR have also started or expanded their own grassland programs.

Many of these efforts aim to think broadly and act at grassland scale. For bird conservation, there’s no choice: Many species, like pipits, make use of the whole North American continent, and others range over the whole western hemisphere. More fundamentally, the myriad threats to US grasslands are simply too big for any group to face alone. I set out to act at grassland scale as well and shadow the pipit’s migration from the plains of Montana to the ranchos of Chihuahua, Mexico.

THREE HOURS SOUTHEAST of Fort Belknap, I meet Bill Milton, a ranching representative for the CGR who runs cattle in the Musselshell plains of Petroleum County. Milton may be the only Montana rancher who is also a Zen priest—a fact that he says informs his “everything is connected” approach to conservation. Milton Ranch has won several land management awards, but mostly Milton focuses on issues that cross fence lines. “If my neighbor is falling apart, [my ranch] will eventually fall apart too,” he tells me at his kitchen table.

A trained facilitator, Milton has helped found several forums and collaborative groups, among them Winnett ACES (Agricultural Community Enhancement and Sustainability), a rancher-led conservation organization based in the nearby town of Winnett. Such local efforts are essential, he says, but they need to plug in to bigger efforts like the CGR. “[People say,] ‘We’re up here protecting Northern Plains grasslands, but the birds winter in Mexico and South America.’ Who’s paying attention to that?”

Critical to CGR, Milton says, is that it gives its local groups leverage on agricultural policy, which is currently at war with itself. For example, in 2023, the Conservation Reserve Program paid farmers nearly $1.8 billion to keep old fields planted with grass. At the same time, other, better funded programs incentivized plowing up grasslands. The renewable fuel standard requires corn ethanol to be mixed into gasoline. After expansion of the RFS in 2007 drove corn prices up by 30 percent, even more grasslands were replaced by cornfields, with predictably dire results for prairie birds. Most of the grasslands lost from 2008 to 2012 were within 100 miles of an ethanol plant. Government-subsidized crop insurance also drives grassland loss, Milton says. The program offers a safety net for farmers but also makes it less risky to cultivate marginal areas, including grasslands.

Policies like the ethanol standard could be reformed in the 2024 Farm Bill, but political realities make prairie advocates skeptical. Instead, they’re thinking about ducks. Because even as many North American bird species have dwindled, waterfowl have become astonishingly abundant. One reason is that in 1989, Congress passed the North American Wetlands Conservation Act, which provides matching funds for the permanent protection of private wetlands (resulting in $6.4 billion in federal and partner funds over its 35-year history). Hunters also fund waterfowl conservation via purchases of duck stamps and equipment taxes.

Prairie advocates hope to mirror that success with the North American Grasslands Conservation Act, which was introduced in Congress in 2022. The original $290 million version failed but has been replaced with a scaled-back version that would still permanently protect grasslands. Tweaks to the Farm Bill—such as reforming the Conservation Reserve Program to provide more and longer-term grassland protection—may also prove politically feasible.

In Montana, Milton is even “poking along” at possible solutions to the vexing problem of crop insurance. Over the summer, he organized a discussion of the issue among ranching, farming, and conservation groups. With enough mutual understanding, he thinks, the group might align on insuring core farmlands without encouraging the plow-up of marginal grasslands. “I think it could be done,” he says. “It’s just having the patience.”

NO ONE KNOWS WHERE exactly the pipits captured in Nancy Raginski’s mist net were headed, but previously tagged birds provide clues about their southern migration. In 2021, a westerly inclined pipit skirted the pumpjacks of Wyoming, passed the booming Denver-Cheyenne corridor, fluttered through the high grasslands of eastern New Mexico, and finally crossed into Mexico. Other birds tacked east of the Black Hills, encountering more fields—and, increasingly, trees, a new impediment to a prairie species—the farther they traveled.

Since 1990, expanding woodlands have eaten half of eastern Kansas, Nebraska, and Oklahoma and two-thirds of Texas. Tree invasion, or “woody encroachment,” is partially driven by higher atmospheric concentrations of carbon dioxide, which helps trees outcompete grasses. It’s also a consequence of fewer elk, which once would have nibbled back woody vegetation in the tallgrass prairie, and the lack of cultural fire, which Indigenous people used to maintain open lands for millennia. “People have been in North America longer than the post-glacial Great Plains have,” said Dillon Fogarty of the University of Nebraska–Lincoln. “The driving factors [for why] this region emerged as a grassland biome were lightning and anthropogenic fire.”

Native nations control about 10 percent of the central grasslands and in many ways are leading the way on wildlife conservation.

Near Maywood, Nebraska, I seek out the Loess Canyons Rangeland Alliance (LCRA), which is bringing fire back to the prairie. The group is less an official organization than a collection of neighbors who banded together to face a crisis. In a grassy valley one morning, I meet up with a multigenerational congregation of dozens of ranch families and allies, all dead set on deforestation.

Participants are alive to the irony of the event taking place in Nebraska, the birthplace of Arbor Day, where people once hand planted a national forest. Even rancher Tell Deatrich, who invited me, admits that “a treeless prairie can be a bleak place.”

Left unchecked, however, eastern red cedar (Juniperus virginiana) forms thickets as dense as Christmas-tree lots. Prairies that previously harbored dozens of plant species quickly become monocultures. Grassland birds like pipits are highly vulnerable to predation by woodland species, so forestation is a kind of habitat loss. Invasive trees have also fueled several destructive megafires and cost ranchers $5 billion in lost forage since 1990. “It’s disastrous ecologically,” Deatrich says. “It destroys communities. We could go get a job somewhere else, but you can only move so long.”

Scientists studying woody encroachment have become more alarmed as they better understand two facts: Without fire and other preventative measures, woody encroachment will eventually come for every prairie, even those once thought invincible; and it is extremely costly, if not impossible, to reverse. That’s why the Natural Resources Conservation Service focuses on preventing encroachment in intact grasslands. Its motto: “Defend the Core, Grow the Core.”

Within that paradigm, the Loess Canyons group is an outlier. By the time the alliance kicked off, science and experience suggested woody encroachment in its area might already be irreversible. But the group is willing to take extraordinary measures, like its “cut and stuff” method—cutting cedar limbs and stuffing them beneath live trees, in effect creating bonfire piles. The LCRA’s largest burn to date was 3,555 acres; it’s now eyeing 10,000 acres.

On the day I join them, alliance members are burning down only a minor forest, about 450 acres. As the grassy hillside before us catches fire, white smoke fills the air. Then the cedars in the creases of the hills catch, and black plumes of smoke rise through the white like exclamation points.

To date, the LCRA is the only group that’s recovered tree-encroached prairies at scale. It has also already saved a population of endangered burrowing beetles. And grassland birds are returning.

AS MIGRATING BIRDS continue their journey south, they see more and more cultivated fields, feedlots, and dairies. Following after them at ground level through Kansas, I sniff the ammoniac air and ponder the weird relationship between cattle and grassland conservation: Ranches provide essential habitat to grassland birds, but most ranchers also sell cattle to feedlots, where they create demand for grains from destroyed prairies.

While they’re on the prairie, cattle also crowd out wildlife, like bison and prairie dogs. Some ranchers vigorously oppose efforts to reintroduce other native wildlife to public, Indigenous, or even private lands. Conversely, some prairie activists welcome wildlife and say the cattle need to share the land. Curtis Freese cofounded American Prairie, an organization that is trying to create a 3.2-million-acre biodiversity reserve in Montana. “We need more and bigger protected areas in the Great Plains,” he said in a YouTube talk. “The Convention on Biological Diversity said 17 percent. We’re at less than 2 percent in the Great Plains.”

But there’s another possible way to coexist with prairie wildlife. It’s the reason Raginski was catching Sprague’s pipits at Fort Belknap. Native nations control about 10 percent of the central grasslands and in many ways are leading the way on wildlife conservation. Fort Belknap, for instance, is one of the only remaining places where bison, prairie dogs, swift foxes, and black-footed ferrets inhabit the same landscape.

“The Central Grasslands Roadmap has worked to be very inclusive of Indigenous people from the beginning. That’s not that common,” Aimee Roberson, a cofounder of CGR’s Indigenous Kinship Circle, told me. Roberson, who is a citizen of the Choctaw Nation of Oklahoma and of Chickasaw descent, said, “We’re really happy to see that people are coming together to ensure that our native grasses continue to grow, bison roam, and that birds fill the skies.”

YELLOW COTTONWOOD leaves ruffle in the autumn wind, as humans and birds continue our journeys south. Above, migrating Swainson’s hawks are on their way to eat grasshoppers all winter on the Argentine pampas, where they’ll be welcomed by another ranching conservation group, the Alianza del Pastizal, or Alliance of Pastures. Down below, I stop for gas and curse the ethanol sticker on the pump, reflecting on how my very trip is made from grasslands: the corn in the gas, the gas itself, the wheat in the (too many) hot-buffalo-wing pretzels. Some landscapes support the illusion that we are separate from nature. Being in the Great Plains is a good reminder that it all comes from somewhere.

Driving south toward Mexico, my mind is dark. Grassland birds are declining because of specific forces, and also, it seems, generalized indifference. A 2013 study found that farm machinery in Canadian fields kills about 320,000 fledgling bobolinks and 480,000 savanna sparrows every year. Up to a million birds drown in uncovered oil pits. And in Mexico, a Baird’s sparrow once flew through airspace that had been open for millennia and hit a utility line. Flagging the lines would help, but nobody wants to spend the money.

Saving grasslands and grassland creatures, I think, will require care from people who live far away. Are we giving back to the places from which we take? And when we take, how much do we waste?

IT WAS ARVIND Panjabi’s colleague who found the Baird’s sparrow on the ground in Chihuahua, Mexico. Panjabi tells me about it as we drive down a dirt road in the arid Mexican state. Before us, yellow grasslands pocked with ocotillos, mesquite trees, and agave run out to a wall of mountains.

A bearish man with a taste for adventure, Panjabi is a senior research scientist with the Bird Conservancy of the Rockies. He coordinates the organization’s work in Mexico and manages a database that tracks the ups and downs of every North American bird species. Back in 2006, Panjabi traveled to Mexico for monitoring. “Then,” he says, “our study sites started disappearing.”

It turned out that the Mexican government had extended utility lines to Chihuahua. In addition to surprising migrating sparrows, the lines brought cheap electricity that could be used to pump groundwater. Mennonite communities began buying ranches, which were struggling with drought and cartel violence, and converting them to irrigated farms. What had been grassland valleys became horizon-to-horizon fields of soybeans, cotton, and corn.

Sprague’s pipits and some 30 other grassland bird species overwinter on Mexican grasslands, which are about a fifth the size of the northern grasslands, so each acre lost has an outsize impact. Prairie birds that overwinter in Mexico are declining twice as fast as other grassland birds; Chihuahua, Panjabi says, is the “weak link” for several species.

Panjabi is working with Mexican ranchers to restore more than 600,000 acres of overgrazed and tree-encroached grasslands. The initiative needs more support. The passage of the North American Grasslands Conservation Act could help: Ten percent of its funding is slated to help protect prairies in Canada and Mexico. Panjabi also recently completed an investment strategy for Mexican grasslands, in part to raise funds to permanently protect a large ranch on the margin of the new agricultural boom.

For three days, I travel with Panjabi, his assistant, and several Mexican colleagues. We meet a new generation of ranchers who are restoring degraded grasslands using holistic land management practices. “The research suggests it shouldn’t work this well, but then you see it and it does,” Panjabi marvels. But trees and fields are clearly on the march. On top of everything, Chihuahua is in a terrible drought; rainfall has been declining for decades. Grassland birds, like humans, desperately need aggressive action on climate change.

One evening, we linger in a healthy, intact grassland full of colorful asters, small shrubs, and stands of blue grama grass. Eduardo Sánchez Murrieta, one of Panjabi’s colleagues, says Mexicans call the grass navajita, or “little knife.” The festive prairie put him in a good mood. He will be returning here soon, conducting his yearly counts of overwintering grassland birds. “There are a lot of birds here in the winter,” he says, smiling amid the grasses and wildflowers. “This is a place that’s good for birds.”

The Magazine of The Sierra Club

The Magazine of The Sierra Club