The "Woke Capitalism" Movement Has Created a Climate Tightrope

When it comes to ESG, Republicans aren't so sure about capitalism

IN MID-APRIL, Brad Lander, the comptroller of New York City, appeared on CNBC's Last Call to debate an obscure Republican presidential candidate: investor Vivek Ramaswamy. The topic of the segment was supposed to be electric vehicles. Instead, the two ended up in a television version of fisticuffs over a little-known abbreviation that has become a new bogeyman for the American right in the culture war: ESG.

"I'm frankly worried about the pension fund plan participants in New York City's pension funds," Ramaswamy said. His pivot to the topic wasn't surprising: Host Brian Sullivan had introduced him as "the godfather of anti-ESG." Ramaswamy had announced his presidential campaign shortly after the launch of his investment firm, Strive Asset Management, which has courted pension funds in Republican states with a pro-oil platform. Ramaswamy wants more, not less, capital to flow into fossil fuels. In his view, "climate-ism" is an ideology, and investing in oil companies is a good way to get rich. "Because you know what? Fossil fuel companies dramatically outperformed the S&P by over 80 percent last year," he said.

Lander oversees around $240 billion in New York's pension funds, and he has spearheaded a plan to make three of the five funds he manages carbon neutral by 2040. He is one of the most outspoken proponents of sustainable investing. Climate change, he argues, is a critical part of calculating long-term wealth generation, and it is imperative to divest from companies whose business models threaten the future of the planet. This intersection—between an awareness that climate change poses a risk to every industry and the traditional capitalist ethic of growing money through a free market system—is what some call environmental, social, and governance (ESG) investing.

"I understand why fossil fuel executives and 2024 presidential candidates are worried about short-term, one-year returns," Lander replied to Ramaswamy. "But I am thinking about a teacher who started teaching this year who is going to work for a couple of decades and expects her or his pension to be there a couple of decades beyond that, long after climate change continues to raise sea levels and temperatures."

The clash was the latest skirmish in a growing national conservative movement to protect fossil fuel industries from climate action and prevent public financial managers like Lander from taking climate into account in their investment decisions. Republican-controlled states have passed legislation that limits how pension fund managers can invest, while state treasurers have pulled business from banks seen as climate-minded. Dozens of conservative attorneys general have issued threats to financial asset managers about their investment choices.

On CNBC, Ramaswamy and Lander seemed like minor figures drawing battle lines in an obscure fight, but their confrontation wasn't just a piece of well-staged political theater. It reflected a broader moment in the cultural zeitgeist that has redrawn traditional party lines, with progressives rallying in favor of market freedom while conservatives try to cast climate-minded investing as part of the culture war. For the new iteration of the Republican Party, molded around identity politics and a sense of grievance in the face of change, the anti-ESG movement has created a climate tightrope: to prohibit in the name of freedom and pollute under the guise of fairness.

Dissatisfied with how the market was turning, right-wing politicians came up with a pet slur for the target of their new campaign. They called it "woke capitalism."

ESG HAS BECOME an easy scapegoat because so few people know what it means. According to a Gallup poll released in spring, 37 percent of Americans reported that they are very or somewhat familiar with ESG, while nearly half reported that they are unfamiliar with it. One poll from Climate Power found that the majority of voters have never heard of it. Adding to the confusion are the degrees of nuance: ESG risk factors may impact a company's financial performance—and thus its investors' outcome. Other categories of sustainable finance, including socially responsible investing (SRI) and impact investing, use investment decisions to proactively create social and environmental value in addition to financial gains.

For the new iteration of the Republican Party, the anti-ESG movement has created a climate tightrope: to prohibit in the name of freedom and pollute under the guise of fairness.

Early attempts to build investment portfolios based on nonfinancial values, in line with SRI, proved popular. In 1990, Amy Domini and her partners launched the Domini 400 Social Index, one of the first socially responsible indexes made up of stocks from large-cap corporations based on their social and environmental standards. She later founded the Domini Social Equity Fund, which by 2006 boasted $160 million in assets. Eventually, it became clear that certain considerations—even social and environmental ones—were beneficial for purely business reasons. In 2004, Paul Clements-Hunt, the former head of the UN Environment Programme Finance Initiative, and a small team coined a term to encourage banks to take certain climate risks and opportunities into account: environmental, social, and governance.

"ESG is about understanding and looking at risks associated with environmental issues, for instance, climate change, lack of resources, lack of water," Danielle Fugere, the president and chief counsel of As You Sow, a nonprofit devoted to promoting shareholder advocacy, told me. "What are those types of problems' impact on business? Investors have a fiduciary duty to their beneficiaries and others to take risks into account and make reasoned decisions."

The method gained its first widespread adoption after the financial crisis of 2008, around issues linked to governance, when shareholders were reeling from the Lehman Brothers meltdown and pushing for companies to take steps that would increase accountability. Over time, the social aspect became key to investors as well, as research demonstrated that socially diverse companies are more resilient and profitable. One report released in 2018 by consulting company McKinsey & Company showed that companies with more ethnic diversity in the executive suite were 33 percent more likely to see profits above the industry average.

In the years since the ESG framework was invented, corporate America and Wall Street have come to embrace it. PricewaterhouseCoopers estimates that more than a fifth of all assets under management worldwide will be ESG-related by 2027; Bloomberg puts that number at one-third. In 2020, $542 billion went into ESG-focused funds, according to Reuters; it rose to at least $649 billion in 2021. Consultancies and funds advise on building ESG portfolios, and some of the biggest asset managers, such as State Street and BlackRock, have established ESG funds, driven not necessarily by climate action or altruism but by the simple logic of capitalism: Where there is demand, there is profit. According to a PricewaterhouseCoopers survey, 90 percent of asset managers believe that investing in ESG will bring better returns on investments, and demand for ESG is still stronger than the ability of the market to provide supply.

Despite its widespread adoption, ESG's criteria can be murky. There is no universal agreement on what kinds of things qualify for the moniker, and so the criteria are generally set by the asset managers themselves. Vanguard, for example, has nine different ESG funds; its US stock ETF (an exchange-traded fund, basically a diversified basket of securities) is made up of holdings in Starbucks, Apple, O'Reilly Automotive, Target, Ford Motor Company, and Colgate-Palmolive, among others. It doesn't allow holdings in coal, oil, gas, alcohol and cannabis, or nuclear, chemical, and biological weapons, and it applies labor and human rights criteria lifted from the UN Global Compact Principles.

Not all ESG-minded funds have chosen to exclude entire industries, though, and the investment community is split on the best way to mitigate risks like those posed by climate change. Some fund managers advocate for divesting from oil and gas companies entirely; the University of California, one of the biggest public school systems in the world, divested its $13.4 billion endowment from fossil fuels. The focus hasn't remained exclusively on the oil industry. Shareholder proposals and activist investors have also pressured banks to stop financing new fossil fuel projects and to disclose the level of exposure they have to climate-induced risks.

Others remain invested in the oil and gas sectors in order to continue engaging and advocating for change as shareholders. In 2020, a newly formed hedge fund named Engine No. 1 launched an activist investor campaign to replace four members of ExxonMobil's executive board, arguing that by ignoring climate change, the oil giant was putting its long-term success in jeopardy.

Engine No. 1's campaign dovetailed with a growing conviction that the liabilities posed by climate change would become material to the entire economy. Major asset managers such as Vanguard, State Street, and BlackRock, as well as global banks and financial institutions, joined alliances committed to decarbonizing economic growth. BlackRock controls about $9 trillion, so when its chief executive, Larry Fink, wrote in his 2021 annual letter to executives that climate change would fundamentally reshape finance around the world, it was a watershed moment.

A raft of data showed not only that it is possible to grow the economy while curtailing fossil fuel dependence (a process often referred to as decoupling) but also that renewable energy sources are beginning to outperform carbon-intensive ones on price. By electrifying as many industries as possible and producing clean electricity, a path to reducing the bulk of climate emissions has started to become clear. This year, $1.70 will be invested in renewable energy for every $1 invested in fossil fuels, according to the International Energy Agency. While the tenets of ESG were still fuzzy and the specter of greenwashing persisted, it seemed like a market consensus was forming around shifting the economy to protect returns.

That's when Republican politicians began to intervene.

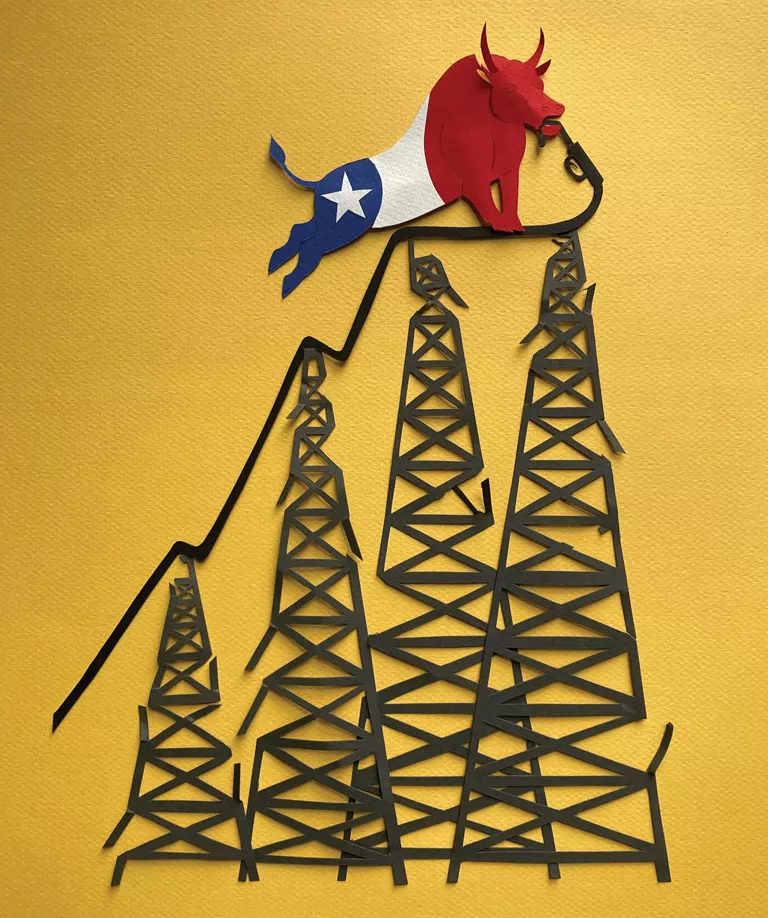

IN 2021, CONSERVATIVE organizations and networks began putting ESG in their crosshairs, backing efforts by Republicans in red-leaning states to introduce legislation to protect the fossil fuel industry. A delegate in West Virginia put forward a bill that March to prohibit state pension funds from investing with companies that were divesting from coal, oil, gas, and petrochemicals. Billionaire oil and gas executive Bud Brigham wrote a white paper outlining what he called the "energy discrimination movement." Legislators in Texas put forward a bill requiring the state's pension funds and school endowment to divest from companies seen as unfriendly to oil and gas. "Oil and gas is the lifeblood of the Texas economy," Representative Phil King said on the floor of the Texas House. "In the world of capital, there's a movement to deny funds to businesses that will not sign on to extreme anti-fossil-fuel policy."

Some of the party's leading figures and other conservative mouthpieces such as Tucker Carlson started to blame ESG for a raft of ills, claiming that the investing strategy was thinly veiled progressive ideology instead of risk aversion. A conservative dark-money group called Consumers' Research poured more than $1 million into ads attacking the chief executives of companies like Nike and Coca-Cola for their labor violations. The group went on to spend millions on a campaign to make ESG the new CRT (critical race theory, another conservative bogeyman), with the support of conservative activist Leonard Leo, who had a hand in orchestrating the overturning of Roe v. Wade.

Another organization supported by Leo, the State Financial Officers Foundation, began to recruit state treasurers to the cause, sparking a furious new political battle among a set of public money managers usually known for avoiding the limelight. The comptroller of Texas announced an investigation into 19 financial companies to determine whether they were "boycotting" the fossil fuel industry. Treasurers in West Virginia and Wyoming began introducing similar decrees, threatening to pull contracts with banks and asset managers that they decided were investing the wrong way. Anti-ESG adherents started to frame investments they didn't like as part of a broader effort to sideline conservatives and undermine the livelihoods of right-leaning citizens.

"People who are trying to make progress on decarbonizing either the US economy or the global economy are running into the buzz saw of some of these crosscurrents that are more about culture-war talking points or hot-button issues or areas of grievance," Dan Firger, the managing director of investment consultant firm Great Circle Capital Advisors, told me. "All these things are bumping up against each other and sloshing around in this big, messy politicized bathtub we're all swimming around in."

Conflating climate-driven investments with cultural schisms is part of what gives the anti-ESG movement its momentum. By associating decarbonization with unrelated controversies, it has moved the conversation away from the investment risks associated with climate change and lent it the sheen of a broader struggle. Florida governor Ron DeSantis has become one of the most outspoken ESG critics, spearheading sweeping legislation that prevents public officials from investing in funds that take environmental, social, or governance factors into account. With DeSantis pursuing the Republican Party's candidacy for president, his views have been taken as a bellwether for the conservative political agenda. "Reining in Big Tech, enforcing antitrust laws, prohibiting discriminatory job training, and crippling the ESG movement are all ways in which the political branches can protect individual freedom from stridently ideological private actors," he writes in his book, The Courage to Be Free.

It's an audacious wager for any conservative politician, since it puts the Republican Party on a course that breaks with its tradition of championing business and free enterprise. Even so, that schism is in keeping with the modern iteration of the party, which has proved willing to throw out long-standing principles for the sake of political expedience. "Among Republicans, it seems to have some traction," Bob Litterman told me. Litterman worked for two decades in risk management at Goldman Sachs before founding his own investment advisory firm, Kepos Capital. "These are people who are trying to oppose any action on climate."

For Litterman and other analysts I spoke to, the campaign against ESG is a direct outcome of ESG's success. With the amount of capital going into ESG funds globally, and the number of corporations that have signed on to net-zero carbon emissions pledges in the past few years, it was only a matter of time before it attracted the attention of politicians. "There are companies—from automobile companies to food companies to agriculture companies—that are moving their processes to be more renewable, from getting rid of internal combustion engines and going to EVs to how they're using water," said Steven Rothstein, managing director of the Ceres Accelerator for Sustainable Capital Markets. "There are hundreds of billions of dollars being invested in changing this. The market is speaking. It is moving in that direction, and it is still moving in that direction despite what's happening in some of these headlines."

The focus on shielding certain industries has struck some as retrogressive. "Why protect a company that clearly will no longer be relevant?" As You Sow's Fugere said. "That is old technology. Why aren't they supporting the technologies of the future? Why are they holding America back? We have always been innovators, and they're saying, 'We won't progress—we must continue to use an old technology that is dirty, that is causing harm, and that is destroying our climate.' Go figure."

THE RULES OF politics seem to follow the laws of physics—each action creates an equal and opposite reaction. Such has been the case for the rise of ESG, which has spawned a shadowy double: the anti-ESG fund.

According to a report released by Morningstar, almost all such funds have appeared within just the past three years. Those funds saw a quick spike of interest, followed by a plateau. Money quickly flocked to new offerings, reaching its apex at $377 million in the third quarter of 2022. Ramaswamy's Strive Asset Management was by far the biggest beneficiary of the boost, capturing 80 percent of capital in the anti-ESG investment space. Since then, though, interest has waned. Strive's second fund attracted $33 million in business during its first month, but the following six funds from Strive received only around $5 million per month after that initial surge.

Legislative efforts have had similarly limited success. One environmental group tracked 165 anti-ESG bills during the 2023 house legislative season and found that most did not become law. Those that did were significantly watered down from the original versions that had been proposed by lawmakers.

Even within Republican-controlled states, where there is broad political support for the platform that the anti-ESG front represents, discomfort with the move to legislate public investment decisions is growing. In private correspondence and lawsuits, financial officers and bankers have started to push back on the legislation, which some of them warn could end up costing pensioners and other investors billions of dollars. In West Virginia, Montana, and Kentucky, the state bankers associations rallied to speak out against what they saw as political interference in their business. In response to the Kentucky attorney general launching an investigation into its investment practices, the state bankers association filed a suit alleging that it "chills the plaintiff's rights to think, speak, and associate freely and without unwarranted governmental intrusion or criticism."

Some pension fund employees have started to view anti-ESG restrictions with skepticism. In an email to fellow treasury employees obtained by investigative nonprofit Documented, John Broussard, Louisiana's chief investment officer, shared his reaction to the BlackRock CEO's statement on climate. "He runs the world's largest investment management firm," Broussard said of Fink. "What he is really talking about is the investment opportunity this movement presents. Some will be winners; some will be losers. That's really what all investment opportunities are."

Evidence is mounting that anti-ESG legislation could lose, not grow, investors' money. An economist and a finance professor from the Wharton School of the University of Pennsylvania set out to study the impact of the Texas anti-ESG rules that went into effect in September 2021. The rules restricted city governments from contracting with certain banks to underwrite municipal bonds. Upon the law's passage, JPMorgan Chase, Goldman Sachs, Citigroup, Bank of America, and Fidelity all withdrew from the market, leaving an enormous hole to fill. As a result, the researchers found, during the first eight months the law had been in effect, the state of Texas paid at least $300 million in extra interest on $32 billion in state bonds.

In Missouri, pension fund employees estimated that complying with anti-ESG legislation would be expensive and burdensome to the state. When the board overseeing the pension fund set up a meeting between fund employees and Ramaswamy, it seemed transparently political. "Mr. Ramaswamy is putting together an ESG-neutral investment option through his newish company, Strive Asset Management," one employee wrote in an email. "My thought is we want to keep this meeting to education and not include someone who is actively recruiting investors for a fund."

Ramaswamy hasn't been shy about broadcasting the political agenda behind his asset management company. Strive's first exchange-traded fund bore the hallmark of that agenda in its ticker symbol: $DRLL.

The office of the New York City comptroller occupies at least half a dozen floors of the David N. Dinkins Manhattan Municipal Building. The Brooklyn Bridge ends at the foot of the building in a cluster of hot dog stands and juice carts, and Lander likes to go on strolls along the pedestrian walkway there. I went to meet him a month after his debate with Ramaswamy, which quickly came up in conversation. "That was fun, actually," he told me with a chuckle.

Lander was elected to the comptroller's office in 2021, after more than a decade on the city council. Before he held public office, he worked in the nonprofit sector on community development at organizations in Brooklyn. When he campaigned for comptroller, he painted himself as a bit of a nerd.

Sitting at his desk under paintings of New York's famous skyline, Lander said that the anti-ESG strategy is deeply clever in how it flattens out investment decisions and converts them into just another part of the culture war. "There's something quite remarkable about the fact that where you would have expected a pro-business Republicanism, there is just a culture war dressed up as pro-business in a way that, if you talk to businesspeople, they're horrified by it," Lander told me.

Lander doubted that the anti-ESG campaign will materially influence the course of finance, but he acknowledged that it has already impacted talks with some of the leading financial institutions. He reported that the conversations he had been having with business and industry about moving to a lower-carbon economy had become politically fraught. "Among investment managers, there was more of a leaning into the understanding that climate risk is financial risk and we should do something about it. And the question was, 'OK, what are you really doing about it?'" Lander said. "There was a sense that there was a gap between the words and the deeds, the words and the actual action. But at least the words were out there. There was the sense that a net-zero commitment was important and meaningful."

One of the things that rankles Lander most about the anti-ESG movement is the chasm between claiming to defend freedom and putting limits on how fiduciaries can invest. A fiduciary is responsible for prioritizing the financial beneficiaries of their fund, which means weighing the potential gains from an investment against the potential risks and making a call according to the aim of the investment and the disposition of the investor. To Lander and many other money managers, it is simply irresponsible to make an investment decision without considering the risks posed by something as cataclysmic as climate change. ESG investors argue that their approach is more profitable for their investments across portfolios, especially over the long term; by encouraging better business, they're growing their money.

"It's a question of persuading people that thinking about the long term is smart, and that's just hard to do," Lander told me. "We're human beings. We want to eat that marshmallow, and we're not good at thinking, 'OK, this year I'll make a little more if I go longer in burning oil, coal, and gas. But what will that mean even just for me—much less for everybody else—judged over the next couple of decades?'"

Lander helped guide three pension funds' plans for net-zero investment portfolios by 2040, which includes making sure asset managers have net-zero goals or "science-based targets and plans" by 2025 and increasing investments in climate solutions to $8.6 billion by 2025 and $37.8 billion by 2035. The crux of the pension funds' argument is that with investment portfolios as diverse as theirs, anything that opens companies up to risk is a bad choice—and if increasing carbon dioxide emissions endangers any business other than oil extraction, the downside outweighs whatever can be gained in the short term from oil profits.

"If every investor said, 'You know what, I think in this year, there will be great money to be made in coal, oil, and gas,' and just keeps doing that for one-year time horizons, it's a prisoner's dilemma," Lander said. "We will burn up trillions of dollars in our portfolio."

The Magazine of The Sierra Club

The Magazine of The Sierra Club