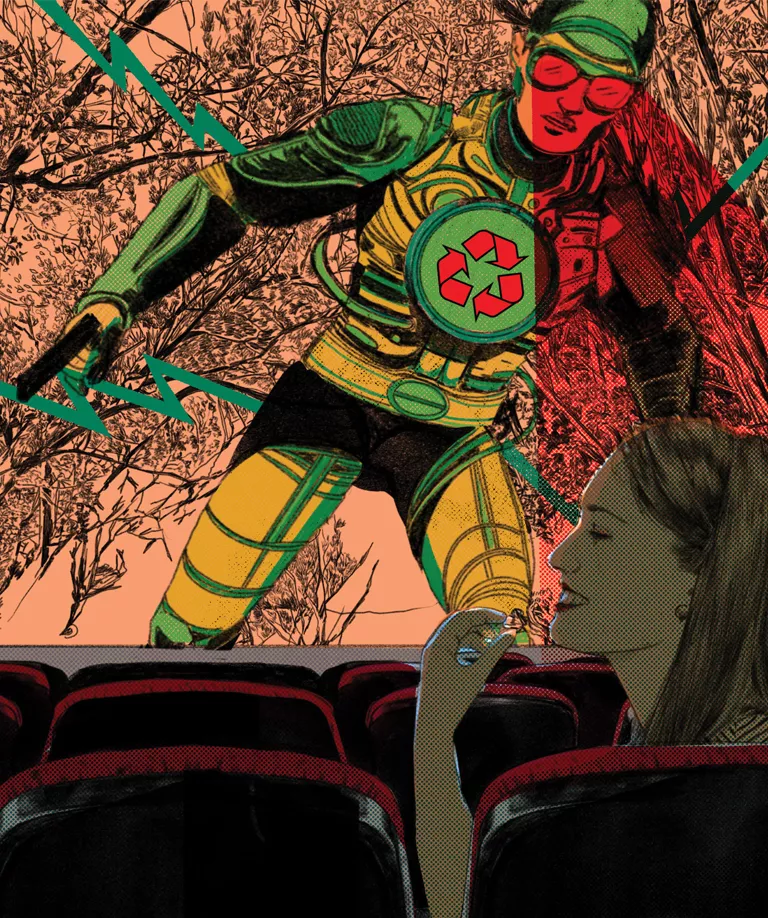

We Don't Need Another Green Anti-Hero

Can Hollywood get beyond its stereotypical portrayals of environmentalists?

Looking back, it seems the problem started with Ghostbusters.

In the 1984 blockbuster comedy, William Atherton plays Environmental Protection Agency investigator Walter Peck. Alarmed by media reports about the Ghostbusters' shenanigans, Peck stops by their headquarters, looking for "the presence of noxious, possibly hazardous-waste chemicals." Ghostbuster Peter Venkman, played by Bill Murray, lies about the existence of an unlicensed fission reactor they're using to imprison captured ghouls—which prompts the EPA official to return with police officers and shut down the rogue nuclear device. Mayhem ensues as the undead take over Manhattan. Peck is emasculated by Venkman in front of the mayor and ultimately buried under a mountain of ectoplasm. The audience merrily cheers at the comeuppance of the unctuous, self-righteous environmental bureaucrat.

In the decades since, film and television depictions of environmentalists haven't evolved much. Environmentalists in pop culture are consistently portrayed as scolds, hypocrites, or Malthusian villains—or all three at once.

Entertainment may be escapist, but it also informs real life. By reinforcing tired stereotypes about greens as hysterical Cassandras, film and television writers are making it harder to grow the movements for ecological sustainability and environmental justice.

Maybe this is no big deal. Entertainment is escape, after all. And part of what makes enviros such juicy targets for writers is that we often take ourselves too seriously; complaining about being depicted as killjoys only reinforces the stereotype. But the environmentalist toxic tropes are genuinely troublesome. Entertainment may be escapist, but it also informs real life. By reinforcing tired stereotypes about greens as hysterical Cassandras, film and television writers are making it harder to grow the movements for ecological sustainability and environmental justice. Few people are going to want to join an effort full of uptight, smarmy doomsayers.

Watch enough film and TV closely and you'll begin to see how the lazy caricatures of environmentalists pop up again and again like the mass-produced, disposable rom-coms crowding the Netflix carousel.

Take 30 Rock's second-season episode "Greenzo." The segment was written as a meta reaction to NBC's "Green Week," during which many prime-time shows were forced to include a positive environmental message. In the fictional 30 Rock universe, David Schwimmer's Greenzo is "America's first nonjudgmental, business-friendly environmental advocate." He appears across a suite of NBC programming, preaching a planet-friendly message. Of course, being judgmental and pious about the environment is the open-pit mine from which comedy gold is extracted. Greenzo, drunk with power, eventually chastises another character, "Do you even bother to compost your own feces?"

Then there is Dwight Schrute's character "Recyclops" in The Office. He starts off by dishing out helpful Earth Day tips, but over six seasons, Recyclops morphs into a demented, aerosol-spraying death robot. On Modern Family, Jesse Eisenberg appears as a smug, über-green neighbor who keeps contracting salmonella; turns out he was undercooking chicken in his solar oven.

It keeps going. One of the biggest recent hits on TV is Paramount's drama series Yellowstone. The hero, John Dutton, played by Kevin Costner, wants to protect his ranch from coastal developers and government bureaucrats. As the state's former livestock commissioner, Dutton also jousts with vegan activists who, during a protest at his office, douse themselves with red paint. The vegans' Portland, Oregon–reared leader, Summer Higgins, exists as a one-note generator of conflict. At one point, she becomes a literal punching bag as she gets into a fistfight with Dutton's daughter. Speaking of hippie punching: It makes for an entire scene in the 1998 film Armageddon, as a heroic oil driller happily hits golf balls at cowering Greenpeace activists.

Making an eco-scold into the butt of the joke may seem harmless. But sometimes lazy character development stretches into darker corners of the imagination. Cue the fictional eco-terrorist. The notion of radical treehuggers looking to extract violent revenge for crimes against the planet bleeds into entertainment. Political- and espionage-themed shows like The Blacklist and Madam Secretary have featured eco-terrorist plotlines. In The West Wing's second-season episode "The Drop In," President Bartlet attacks moderate enviros for not condemning eco-terrorists, all in a calculated effort to appease his Republican antagonists.

On the big screen, eco-villains scheme to steal Bolivia's water from peasants in James Bond's Quantum of Solace, and they unleash a horde of kaijus in Godzilla: King of the Monsters. In the time-bending dystopia 12 Monkeys, a misanthropic band of animal-rights activists are the prime suspects in the unleashing of a civilization-destroying pandemic. (Spoiler alert: They didn't do it, but their role as a convenient foil only helps to prove the point.) Amid these unsympathetic characters, the eco-terrorist Oscar goes to Marvel's Thanos. After acquiring godlike powers in Avengers: Infinity War, Thanos annihilates half the universe with the snap of his fingers to preserve enough food and resources for the other half.

Using characters like the environmental scold and the eco-terrorist—along with the dastardly oil executive and the villainous chemical plant owner—may be convenient for movie and TV creators. But in the era of intensifying climate chaos and burgeoning environmental activism, such stereotypes are increasingly anachronistic. Hollywood's green tropes are at risk of being inauthentic—and inauthentic storytelling doesn't sell movie tickets or streaming subscriptions.

The majority of Americans—and a supermajority of young Americans—are concerned about climate change. Research from the script consultants at Good Energy Stories has found that contemporary audiences care more about climate change than the characters they see onscreen do. That disconnect between where the audience is in terms of environmental commitment and what kind of programming they're being offered could prove troublesome for show business. "At some point, that becomes a problem," said Good Energy founder Anna Jane Joyner. "It's not just about doing something right; it also makes the story you're telling authentic to the world we live in."

Scott Z. Burns, the creator of Apple TV's climate-change-driven series Extrapolations, agrees. "When you do a show, you need to build a character that's a fully realized human being," he said. "If not, you end up with a shorthand that's the young, crazy vegan radical or the old hippie that never grew up. Both of those stereotypes are not great writing. They're also not fair to how integrated environmentalism has become in our day-to-day lives. There are people who are conscious of their impact in pretty much every line of work. Even bankers."

The increasing urgency of the climate crisis appears to be leading to a shift—though a slow one—in how environmentalists are portrayed on-screen. On Apple TV's critically acclaimed Ted Lasso, the lovable character Sam Obisanya leads a protest against the team's sponsor, which is polluting his Nigerian homeland. Even the eco-saboteur has gotten a Hollywood makeover. The 2018 Icelandic film Woman at War is a warm portrait of a passionate, determined heroine who sabotages the construction of a nearby aluminum plant; she is also the local choir director. And How to Blow Up a Pipeline, an indie flick released earlier this year, took an Edward Abbey–like plotline and turned it into an Ocean's Eleven–style heist movie. The ragtag protagonists bring to mind the scrappy rebels from Star Wars, with the oil and gas industry as the Empire.

Vulture TV critic Jen Chaney believes that the 2021 climate apocalypse satire Don't Look Up will be viewed as a turning point in how environmentalists are portrayed. Director Adam McKay starts with the trope of the environmentalist scolds—a mismatched pair of astronomers played by Leonardo DiCaprio and Jennifer Lawrence—but then makes them empathetic. DiCaprio's astronomer is endearingly anxious; Lawrence's character is at once idealistic and world-weary. "That's an unusual approach," Chaney said.

Ideally, film and TV writers won't just overcorrect and replace the green antihero with the green hero. One-note characters, whether Bond villain or superhero, are boring. Audiences don't need unblemished environmental saviors. They need, rather, environmentally minded characters who are flawed and relatable, no matter their stance on the viability of plastic recycling. That is, characters who are at once forgiving and sanctimonious, scared and courageous, bold and humble, fueled by passion and riven by doubt.

Hopefully, Hollywood will realize sooner rather than later that environmentalists are just like everyone else—both admirable and screwed up in all the usual ways. When that realization hits, environmentalists will finally go from recycled cliché to center stage, the sort of protagonists who can even defeat the Stay Puft Marshmallow Man.

The Magazine of The Sierra Club

The Magazine of The Sierra Club