Spoken Word: Inside the Rogue, Homegrown World of Bike Zines

How they make space for people outside the margins of US car culture

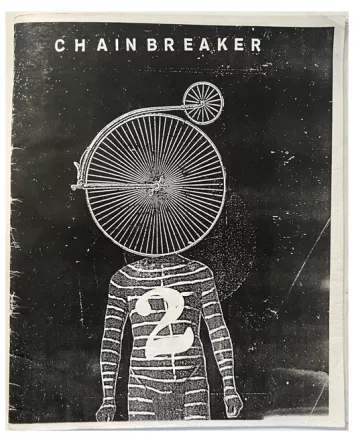

Illustration By Tim Robinson

One evening in the early 2000s, I found myself alone on the shoulder of a dusty Kansas highway at sunset. I had a flat bike tire and no clue how to change it. For nearly two months, I had been pedaling a meandering network of back roads from the Oregon coast toward Missouri with most of my earthly belongings strapped to my bike rack. Until that day, mechanical problems had been hypothetical; they seemed as unlikely as finding vegan options in a rural diner. The road was empty, the sky was growing dark, and I didn't have a cellphone to call for advice or a ride to my campsite. What I did have, stuffed deep inside a handlebar bag, was my cycling bible: a damp and crumpled issue of Chainbreaker.

The bike zine saved me. And I'm not only talking about that incident. I had been reading zines—those self-published booklets traded and sold at alt-bookshops and underground show venues—since the medium's resurgence in the early 1990s. But Chainbreaker was the first one that really spoke to me: a scruffy, queer, bike-obsessed oddball from the car-centric Midwest. Created by bike mechanics Shelley Lynn Jackson and Ethan Clark, Chainbreaker emanated warmth, encouragement, and humor. The zine included step-by-step maintenance tips, an illustrated guide to bike tools, and tales of life as a female bike mechanic in a way that celebrated a low-cost, DIY, and often feminist sensibility. Accustomed to being dismissed or talked down to in bike shops—and overlooked completely by Lance Armstrong–focused mainstream cycling publications—I found a place for myself in Chainbreaker's photocopied pages. In 2006, I was inspired to start my own zine, Spokes of Hazard, to chronicle my many bike-touring mishaps.

What I never expected is that so many years later, zines would be more culturally relevant than ever. Newcomers to the zine world are often surprised that they still exist in the digital era—that an entire community has formed around creating them, trading them, and meeting up at big events, like the annual Portland Zine Symposium. Today's zines are not only thriving; they've also gone multimedia, existing in hard-copy, hastily stapled form and as digital re-creations posted to Instagram and other social platforms. Heck, even Kanye West has one (to hype his shoe line).

You can order zines from distributors like Microcosm Publishing, Brown Recluse, and Pioneers Press on topics as diverse as coping with grief, identifying urban plants, managing personal finances, and hopping trains. More memoirish zines detail the lives of the neurodiverse, ex-felons, radical parents, and other self-identified outsiders. Such spaces are sorely needed in the bike media community, which has for so long focused strictly on biking for speed and fitness, to the exclusion of those of us who ride for transportation, politics, or pure joy. Even in 2022, zines are where I turn first for DIY repairs and narratives on topics relevant to the biking world, like riding with a disability and the policing of communities of color on bikes.

Zine-maker Christina Torres started commuting by bike in 2009, when she could no longer afford the bus as a student in San Francisco. From the beginning, Torres loved cruising past cars stuck in gridlocked traffic and arriving to work aglow from the effort of pedaling. Over time, she fell in love with how riding connected her to the outdoors and the land in a way that felt medicinal—it revived her and gave her a surge of well-being.

But Torres didn't see herself represented in media about bikes—which typically catered to older, upscale, white, male road cyclists. Alternative bike communities were rarely represented, let alone women, trans people, and people of color. So Torres decided to create that space, unveiling the revolutionary Cyclista Zine in 2019 as "an intersectional radical feminist response to the cycling industry" that chronicles the stories of WTF (women, trans, femme) cyclists as well as riders of color. Online, she put out calls for contributors to write about their bikes as they related to mental illness or disabilities, or to race, class, gender, and other identities. "Welcome to Cyclista Zine, where we aim to shred the patriarchy!" read her kick-off Instagram post. The resultant print issues of Cyclista include everything I love about the DIY spirit and welcoming nature of Chainbreaker, and amplify the inclusivity and "personal is political" appeal.

Tiffany F. Lam's excellent Mind the Cycling Gender Gap takes the stat that women make up just 28 percent of all bike commuters in the United States and humanizes it through the stories of women all over the world who ride, documenting the challenges they face in navigating unsafe streets lacking in bike infrastructure. Similarly, Bikequity: Money, Class, & Bicycling, a book edited by Elly Blue of Microcosm Publishing (also the publisher of Lam's zine and hundreds of others), examines the class components of cycling and the unintended consequences bikes can have on a neighborhood—particularly how they can be used as a tool for gentrification.

Blue's book sprang out of her bike zine Taking the Lane, which started as a catalog of the daily sexism she faced as a woman on a bike in Portland, from the pressure to volunteer for bike organizations "because we need more women" to gendered harassment from motorists. From there, it has grown into one of the most influential bike zines of the past decade, name-checked by all the zinesters I spoke with for this story. Over the course of 15 issues, Taking the Lane explores unexpected themes: childhood, science fiction, sexuality, pets, religion, trans identities. Where else can you find cycling sci-fi and the story of the Sprockettes, the world's first all-women mini-bicycle dance troupe?

Journalist Sarah Mirk began publishing a short, folded print comic every day of 2019 as part of her Zine a Day project. Biking for everyday transportation is a steady through line in her work, as is confronting big issues like climate anxiety. "One reason I love biking is because I just want to be able to get myself wherever I want to go," Mirk says. "It feels so nice to move myself around, like, 'My body did this.' Zines are the same way—when I have something I want to express, I can put it down on paper and get it out there, and it's a similar feeling of self-expression, like, 'I made this; this came from me.'"

You don't need an editor or a budget or even a wi-fi connection to make a zine. And you won't make much money—it's an act that's done for the simple joy of creative expression, which feels increasingly rare in modern life. "Both bikes and zines can be really affordable," Mirk says. "And as with bikes, you don't have to pay for car insurance or gas, so they work for people who don't have a lot of money or have an anti-capitalist bent." Another plus, Blue points out, is that there's no comments section—so outside voices are free to express themselves without the relentless backlash that comes with writing for more-mainstream cycling outlets, not to mention bike social media.

Almost two decades and four cross-country moves after my mishap in Kansas, I still have the battered issues of Chainbreaker that taught me how to change my first flat tire and made me feel like I could express everything I love about bikes—in all its typewritten imperfection. Since then, I've added to the stack: Momentum Mag, Velo Vixen, Boneshaker, Pedal by Pedal, and more. Soon I'll check out new ones recommended by Mirk, Blue, and Torres: Corking, Get Rad Be Radical, Yolow, and Bicycle Culture Rising.

These simple photocopied pages have helped so many of us find our voices and our communities. They're the reason we still write and still ride.

This article appeared in the Spring 2022 quarterly edition with the headline "Spoke 'n' Word."

The Magazine of The Sierra Club

The Magazine of The Sierra Club