Field-Tripping Adults Chase Megalodon in Monterey Bay

How I traveled through time during the pandemic

Paleontologist Wayne Thompson | Photos by Gabriela Hasbun

"That rock has a lot to tell us," says the paleontologist I met a minute ago. "Wanna go say hi?" I do, so I follow him toward a moss-covered boulder, stumbling over slippery stones, knee-deep in central California's Monterey Bay. In our flip-flops and floppy hats, we strike quite the contrast with our fellow beachgoers, slick surfers chasing waves on a sunny afternoon.

How did I get here? A few weeks prior, my science-enthusiast boyfriend, Kevin, had learned that this stretch of coastline's complex tectonic history makes it easy to unearth prehistoric seashells, crabs, teeth, and whatnot. He proposed, with the gusto of a precocious 10-year-old, that we take a "fossil-hunting vacation."

Eager for any change in pandemic scenery, I obliged. A friend of a friend of a friend suggested we look up Wayne Thompson, a local paleontologist and middle school science teacher who often collaborates with the US Geological Survey and area museums. Thompson immediately responded to a cold email with an invitation to meet him at the shore for a "walk through time."

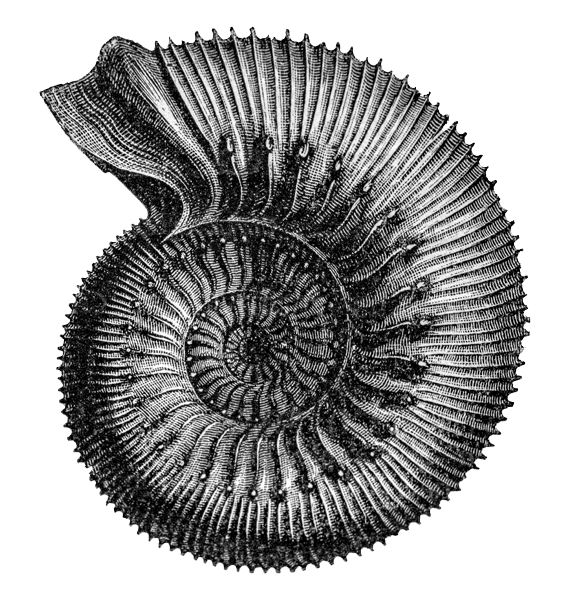

Monterey Bay, Thompson says, has "an embarrassment of riches in the form of prehistoric bivalves and gastropods."

The moment we arrive at the appointed stretch of narrow, rocky beach, shielded from the Santa Cruz–bound traffic above by towering sedimentary cliffs, it's clear that Thompson—a burly, sun-weathered rock hound—knows his way around a field trip. Our upbeat guide hands us each a paleontological "collecting pack" consisting of a hammer, a dental pick, a toothbrush, a chisel, and some old alt-weekly newspapers for wrapping up our finds. "Don't worry!" he says, catching the surprise on my face. "I won't let you take anything rare. But we've got an embarrassment of riches in the form of prehistoric bivalves and gastropods." There are, in fact, millions of ancient clams, rays, shrimp, snails, and starfish embedded in these cliff walls. Thompson is used to this—he's been digging at this spot for 44 years—but I feel a tremor of excitement like when I was a kid on a field trip and got to participate in actual science.

Thompson's own childhood in nearby Scotts Valley set him on his life course. His family owned a roadside attraction called the Lost World, a now-defunct amusement park celebrating the Jurassic period. Whenever the triceratops—his favorite among the park's many life-size animatronic fiberglass dinosaurs—broke down, he says, "it meant my brother and I could climb inside the belly of the huge beast to reach the giant I beams rocking the head and growl at the guests strolling through the park in our best dinosaur voices." In the 1960s, one of the dinosaurs was stolen and dumped in the front yard of folk icon Joan Baez, who kindly returned it.

Over the course of his career, Thompson has excavated triceratops skulls in Montana's Hell Creek Formation and unearthed ancient whales in California's Humboldt and Santa Cruz Counties. But his true passion lies in Monterey Bay, near where he grew up. "Going to the same place for so many decades and looking at the creatures that have lived here over time, it's emotional," he says. "The rock record gives a sense of the impact of global shifts like climate change, and you can tap into the bigger cycles beyond the boundaries of what you normally see when you look at the environment around you."

Today, we are on the prowl for an as-yet-uncategorized snail—a member of the genus Trochita—that Thompson describes as a "mini volcano." Should Kevin or I spot one, Thompson will spend up to 90 minutes chiseling it out of the rock without damaging it before sharing it with the research community for identification, and we'll be part of natural history in the making. As we vigilantly wade, Thompson tells us about the mastodons and giant walruses that once roamed where we're standing at various points in history.

Sedimentary layers preserve the ancient seafloor.

Thanks to two dozen faults and hundreds of micro faults, this three-quarter-mile stretch of craggy coastline has tectonically shifted over the past 4.5 million years to the point where the sedimentary layers of cliff face behind us appear striped, like a lasagna tilted slightly to one side. "The lower portion of the cliffs times in about when megalodon was swimming here," Thompson says, referring to the extinct big-toothed shark—familiar to viewers of Shark Week—dating back 6.7 million years. "Now let's go see what the strata are saying to us."

Over the sound of crashing waves, Thompson explains how the cliffs and rocks all around show the transgression and regression of sea levels as slight changes in the earth's orbit around the sun either grew or shrank the ice caps over the past few million years. Each stratified layer, he says, represents a different slice of the seafloor's history, with up to a million years compressed in a single layer. "The further you go up, the newer the natural history is."

Lost World theme park guests pose by one of the roadside attraction's dozens of life-size, animatronic dinosaurs.

Surveying the cliff's middle layer, Thompson excitedly points out whale ear bones (tympanic bullae) deposited into the seabed during the Pliocene as well as the haunting outlines of pinniped skulls. Thompson spots dozens of vertebrate fossils each year and identifies 12 to 14. Recently, he uncovered a giant walrus's anklebone and tusk. That's in addition to the thousands of ancient snails and barnacles (including a rare, feathery variety that lives only on whales) and all manner of mollusks and gastropods he regularly finds.

I have to admit, this is the first time I've gone to the seashore and looked intently in the other direction. And I've certainly never tried to listen to what a rock has to say. But after Thompson shows me and Kevin how to spot active erosion in the watery earth, how to take note of structures that repeat themselves (a sure sign that there's more to a chunk of rock, as living organisms' DNA creates consistency of shape), and how to gently chisel out preserved sea creatures, I realize just how rife with life, past and present, seemingly static landscapes can be. I vow never to take a rock at face value again.

We do, in fact, become rogue citizen scientists that day. After wrapping dozens of clam fossils, many hidden beneath intricate layers of shell, Kevin spots a snailish specimen that does look exactly like a little volcano.

This article appeared in the Summer quarterly edition with the headline "Chasing Megalodon in Monterey Bay."

PLAN YOUR OWN DIG

WHERE

WHERE

While not every state is ideal for fossil hunting, there are plenty of opportunities to get in touch with prehistoric creatures and plants. (Note that each state has its own laws for fossil collection. Some locations require permits, and others forbid it altogether. Do your research before picking up a rock hammer.)

WHAT TO LOOK FOR

A good indicator that your local landscape contains remains of ancient life is exposed sedimentary rock around creeks, rivers, shorelines, and other areas of active erosion. You're in the right sort of place if you see sandstone. You're unlikely to find fossils in other kinds of rock.

WHAT NEXT?

If you find something, it's best to leave it in place, photograph it, and map the spot. Then look for an expert at a local museum or check with the Society of Vertebrate Paleontology. You can always bone up on fossils in the digital repositories of thefossilforum.com.

The Magazine of The Sierra Club

The Magazine of The Sierra Club