One Man's Drive to Save a Coral Reef in Cuba

Nene leverages sustainable tourism to help a dying reef

Nene cleans algae off a piece of coral. | Photos by Dr. Shireen Rahimi

Soy músico, poeta, y loco.

"I am a musician, a poet, and crazy" is a common saying in Cuba when somebody finds creative solutions to a problem. That's how Reinaldo Borrego Hernández, who goes by Nene, describes himself and his work to save the coral reef near his childhood home.

Nene grew up in the 1980s in Cocodrilo, a small coastal village on the Isle of Youth in western Cuba. Nene's family was poor; the only games he could play were with the ocean. He spent his days skirting the curved, rocky coastline and its white beaches, watching sea turtles make their nests, and diving in the Caribbean to explore coral reefs, where striped parrotfish and blue-striped grunts circulated among sea stars bursting in a kaleidoscope of colors.

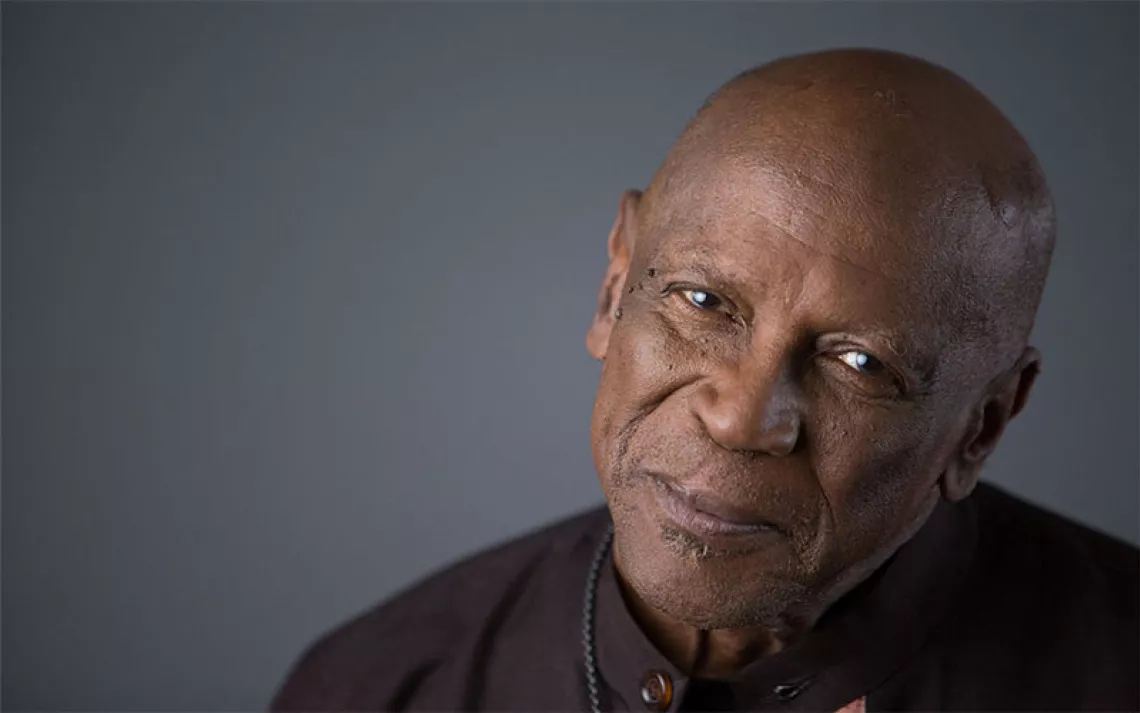

Reinaldo "Nene" Borrego Hernández, at home in Cuba

Nene went on to work as a ranger and eventually became the director of Punta Francés National Park, where he was tasked with conserving the coral reef that had defined his childhood.

Today, he is in a race against time to save it.

Commercial fishing and spearfishing—a way of life for Cuba's low-income coastal communities—are clearing the island nation's coastal waters of its most prized inhabitants, such as lobsters and snappers. In 1997, Cuba passed some of the strictest environmental laws in the world to protect these areas and create elaborate coral reef preserves. Yet they still suffer from overfishing and a lack of money and workers to enforce the laws.

A decrease in apex predators, like sharks and groupers, combined with an increase in water temperatures and hurricanes intensified by climate change has led to a reef crisis off the coast of Cocodrilo. Herbivore fish, which eat the algae that compete with corals for reef space, are now less common.

"In the reef, there are no more big fish," Nene said. "If the big fish are missing, the whole chain is disrupted," all the way down to the coral.

In 2014, Nene left his position as park director to complete a master's degree at the University of Havana. He wanted to study how a community could live sustainably in a protected area—and how to stop the Cocodrilo reef from dying.

A thriving staghorn coral planted four years ago

Someone would have to manually remove the suffocating algae from the coral piece by piece and plant new, healthy coral, Nene concluded—a task too big to take on alone. He needed help. As he was trying to formulate a plan, he had a thought: There had long been a thriving tourism industry in the coastal communities of Cuba. Why not organize these visitors to help him save the reef?

It's common practice for Cubans to rent out their living spaces to tourists as bed-and-breakfasts. In 2016, Nene decided to do the same but with an added purpose: He would rent his space to those interested in helping him preserve the reef.

Johann Besserer is the founder of the nonprofit Intercultural Outreach Initiative. Every year, IOI sends up to 20 volunteers to stay at Nene's bed-and-breakfast for about three weeks. From the moment they arrive, guests clear plastic off the beach and help maintain Nene's coral-reforestation area.

"He's an absolute hero for environmental protection," Besserer said.

In 2017, Nene organized a free advanced scuba-diving course for village teenagers to teach them how to link ocean conservation with tourism and educate them about the ecological effects of illegal fishing. It did not go unnoticed. Police arrived and questioned what he was doing, accused him of illicit commercial activity, and threw him in jail for a few days. (The government eventually acknowledged that Nene was doing no harm and dismissed the charges.)

In December 2019, I traveled to Cuba to learn more about Nene's model for environmentally oriented tourism. During a dive to see the reef, we swam a few meters down. I followed him through dappled, glaucous waters out to two buoys placed mid-water with ropes running to the seafloor. Along each line, there were three horizontal sticks of decreasing length from which pieces of staghorn coral (Acropora cervicornis) hung in tangerine fingers, enriched by floating nutrients and scattered light—their sustenance. After cultivating the coral pieces for a year, Nene plants them on the reef.

He showed me the reef soon after—it looked bleached and bland, like a layer cake of bones. But in the area where the coral had regrown on the reef, the change was astonishing: an explosion of color with clouds of fish wandering all around. They looked like loamy stars in a forgotten universe.

It's a game of inches on a miles-long field. However, the effects of this project are felt beyond Cocodrilo: The Gulf Stream takes the larvae of reef fish and lobsters hatched in the Cuba reef ecosystem into Mexican and American waters, where they replenish other communities' impoverished fish stocks.

In 2021, Nene received approval to start a new educational coral-conservation project with the University of Havana to involve more youths.

"I dream that young people will link tourism with conservation as an alternative to illegal fishing," Nene said. "If we don't do that, our natural resources will disappear, and then we won't have anything left."

This article appeared in the Summer quarterly edition with the headline "The Reef Protector."

The Magazine of The Sierra Club

The Magazine of The Sierra Club