One Hiker Takes Her COVID-Stricken Mother on an Unexpected Journey

Inside their trek through the Blue Ridge Mountains and rural Somali villages

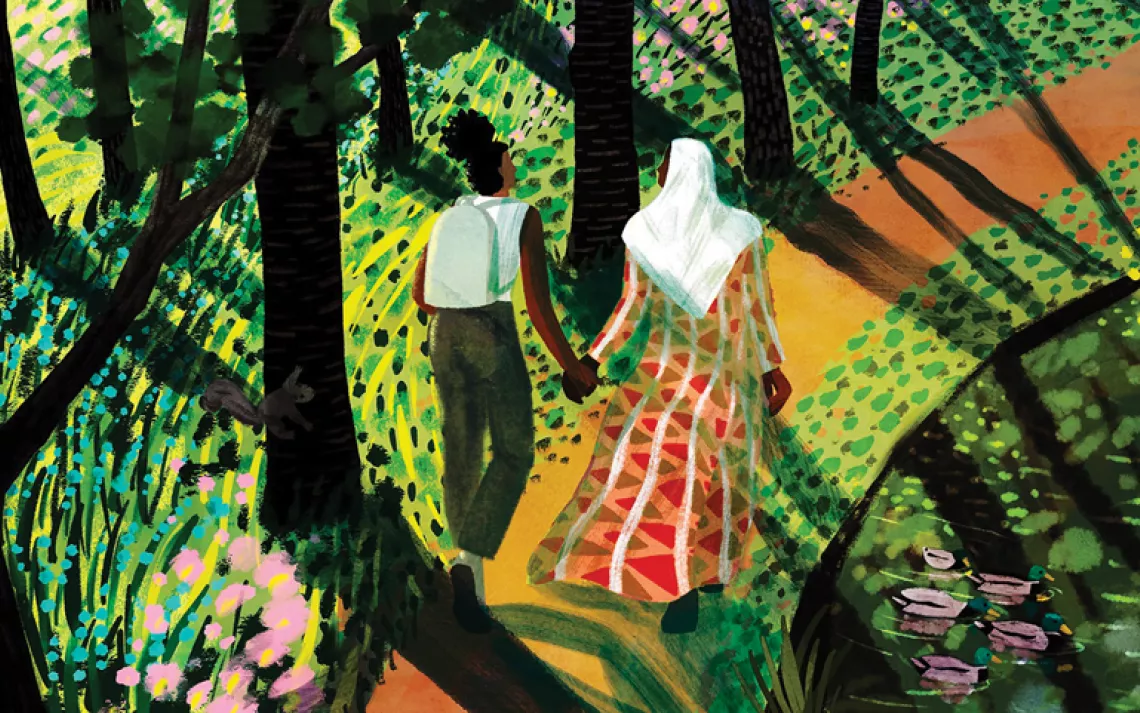

Illustration by Sirin Thada

"You know, the doctor says I have to keep moving so my lungs do not fill up with fluid. I should do what you do," said my mother. I call her Hoyo—that's the Somali word for "mother." She was sitting on a chair in the middle of the garage, next to a bag of clothes bound for the donation center. I was several feet away from her, in the driveway, perched on the hood of my car. We both had our masks on. "Hike, you mean hike," I said. I knew she did not have the language for it.

It was a Sunday afternoon in September when my sister called to tell me that both my parents had contracted COVID-19. I got in my car at 7 A.M. the next morning and drove the 20 hours from Denver to Ohio. It was a surreal experience, driving as if my presence could cure the uncertainty of a novel virus. I just wanted to be there, to be as close as I could without contracting the virus. I checked in at a hotel, and every morning at a nearby park, I hiked.

In Somali culture, leisure hiking is not a thing. Years ago, the first time I told my mother I was going on a hiking trip in Virginia's Blue Ridge Mountains, she asked why. When I responded "because I want to," she went on to tell me that I was bored and should find a second job. She could understand hiking from her rural Somali village to another. Somali nomads trekked for a purpose. For food, shelter, and work—but not for leisure, never for enjoyment.

Each of the six days I was in Ohio, I came to sit in the driveway, sometimes still in my hiking clothes. That sunny afternoon, Hoyo looked at me sitting atop my car and said, "Tell me about it, this hiking. What's it like?" I spoke, in Somali, with the eagerness of someone who'd left home and returned to tell tales of worlds beyond. "It's like walking but with fewer limitations. No stoplights or pavement. The trails are all different. I walk as fast or as slow as I want, and the reward is the quiet, the greenery." Hoyo, smiling with the blue-green eyes I adored, just looked at me. "Oh, and there are mountains, and each range is different. The Rockies are incredible, but so are the Catskills. I lived there too, you know. And there are animals, wild and beautiful in their glory."

It went on like this for hours as I watched her eat her lunch that she could not taste. Hoyo, occasionally stopping to cough, told me stories about her bell-bottom-wearing friends in Somalia mimicking Michael Jackson's Afro and style. She laughed to herself as the memories flooded. "It was the '70s, and we were having fun." Her stories spoke to a youth she had never mentioned. For years, my nomadic life had separated us. We only spoke about my whereabouts, not why I loved traveling, exploring, and living in mountain towns.

That week, when her muscles ached all over, when she was fighting an illness that terrified all of us, was different. Meanwhile, my dad stayed in the house, nursing a slight case of pneumonia. "It affects everyone differently," Hoyo said at some point, after going in to check on him.

I went to see her again in October, and then in November. By then, both my parents had recovered. Now it seems like Hoyo has a lifetime of stories to tell. Watching her tell me and my sister, over FaceTime, about the songs she sang as a child, one would think we had all been this close all our lives. I want us to continue getting to know each other for as long as we can. For me, it's very much like hiking—it doesn't matter how we got here, as long as we keep going.

This article appeared in the March/April edition with the headline "Journeys With My Mother."

The Magazine of The Sierra Club

The Magazine of The Sierra Club