A Poet, a Nebula, and the State of California

What would it take to see the planet beyond our own mythology of need?

Illustration by Maggie Chiang

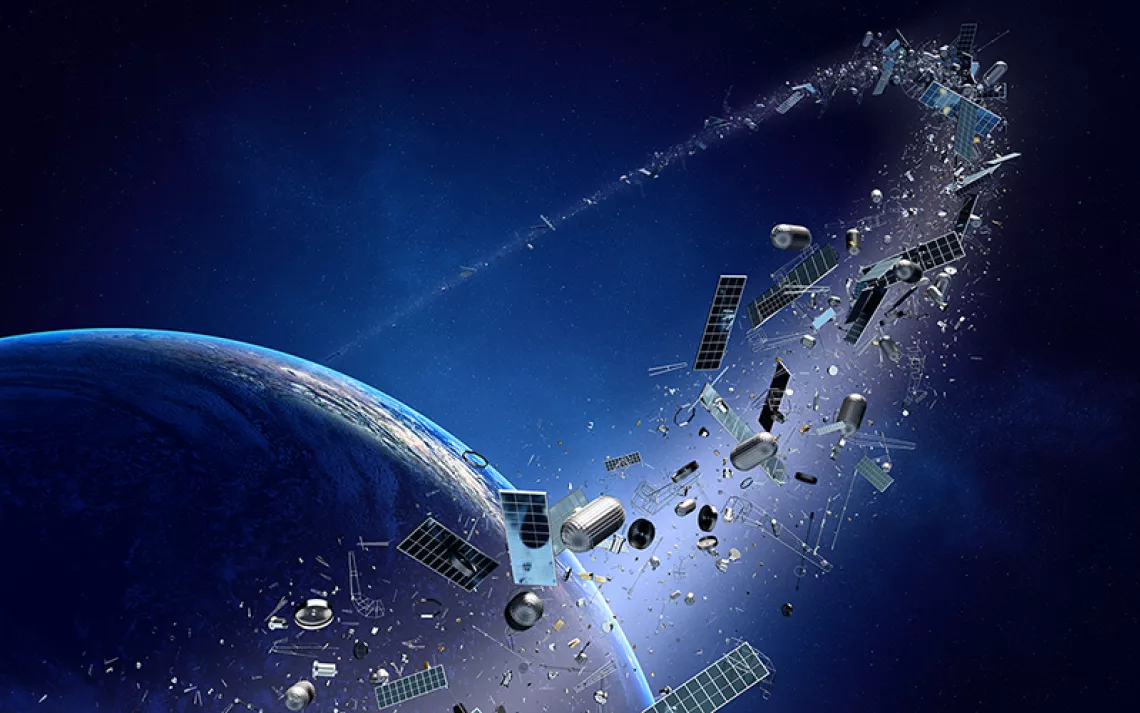

If I could look 1,000 light-years up, I would see a red stretch of outer space called NGC 1499, or the California Nebula. It's spread across 100 light-years, or, as Sky Guide says, "the length of five full moons." The long wavelengths of red are hard to see. The nebula has such low surface brightness.

Several amateur astrophotographers have taken pictures of this nebula from their backyards. You need a long exposure to hold it, that emission nebula, evidence of ionized gas from a nearby hot and uncontainable star. They say it looks like the state of California, and as it moves through the spiral arm of the Milky Way, it lines up with the state at its zenith. In the week that I am writing this, California has announced that it is phasing out all new cars powered by gasoline by 2035. This is the state's boldest belated response to the problem of emissions. Not the natural emissions of a star being a star, but the toxic emissions of our species burning up fossils to move through lateral space.

By the time you read this, that news will be old. The California Nebula is 1,000 light-years away, which means even if I could see it, I would be late, vaguely observing what the emissions from the bright star Xi Persei looked like a thousand years ago. Is it still as bright or as dull? What is it emitting today? I will not live to know.

So then, why do I look up? Because I crave a longer perspective. Looking up, allowing myself to perceive or imagine light reflected to me from 1,000 light-years away makes me feel both small and expansive. And while movies set in space and private shuttles to other planets seem to be fueled by futurism, I would say that they are just as obsessed with the past. They are backward facing. When I look into the stars, I am looking into a past long before my lifetime. And I wonder if the desire for a private ticket to Mars is not futuristic at all but actually nostalgic for a landscape as yet unspoiled by human messiness, for a childhood when so much more felt possible.

This morning, I was thinking about my parents' divorce. At the beginning of the end of their marriage, they took a trip to California. San Francisco. My mother remembers the fog, that it was colder, wetter than she had imagined. They could almost never see the sky. But my mother also remembers when she finally saw my father, really saw him beyond the fairy-tale story of romance and marriage she had projected onto him since they met. And she was finally ready to honor what she saw, but it was too late. Like so many stars, by the time she could really see him, he was gone.

My parents stayed close friends and loving co-parents until my father passed away four years ago from prostate cancer, also detected too late. And I feel that it is only now that I am truly seeing him, beyond what I had projected about safety and home and superheroes. How much sooner would have been soon enough, to see what is not bright at the surface, what is diffuse and spread across the century? The possibility of love right where we are. Five full moons sooner? What would it take to see the planet we are on beyond our own mythology of need? Or maybe more important, 100 years from now, 1,000 light-years from here, what will they say about what we emitted, our nebulous state of ionization? How diffuse and how perceptible? How red?

This article appeared in the January/February edition with the headline "One Hundred Light-Years."

The Magazine of The Sierra Club

The Magazine of The Sierra Club