Car Culture and Systemic Racism Collide

Automobile dependence enables police violence against Black people

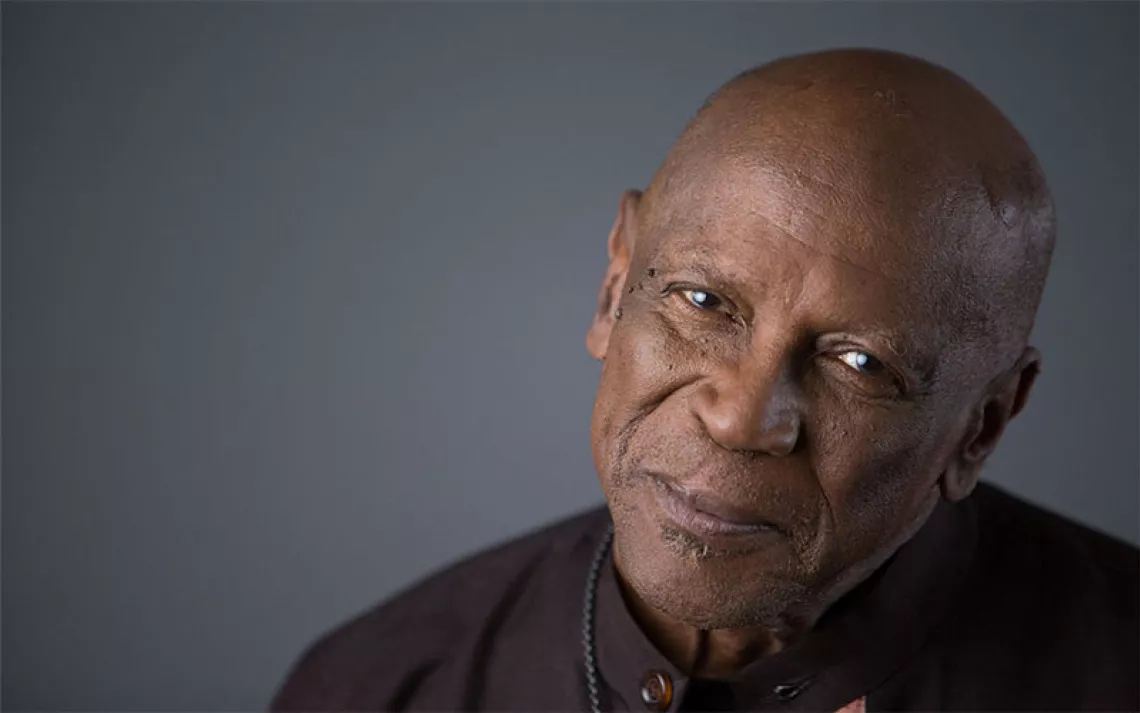

Illustration by Noa Denmon

Philando Castile, shot and killed by a police officer after being stopped for a broken taillight. Sandra Bland, pulled over for failing to signal a lane change and subsequently found dead in her jail cell. Samuel DuBose, shot to death by a police officer who had stopped him for a missing front license plate. For Black Americans, minor traffic infractions can turn deadly. One reason is systemic racism in the nation's police departments. Another reason is cars.

The one is related to the other. According to the Justice Department's Bureau of Justice Statistics, 52 percent of people's interactions with the police come in the form of traffic stops. The DOJ has also found that African Americans and Latinos stopped by the police are more than twice as likely to experience the threat or use of physical force as whites.

Policing as we know it today, writes Sarah A. Seo in Policing the Open Road: How Cars Transformed American Freedom, arose largely in response to a need to regulate the bad driving that inevitably accompanied the widespread adoption of the automobile. "Before cars," Seo says, "police mainly dealt with those on the margins of society." But with millions of people suddenly driving cars, "officers now required discretion to administer the massive traffic-enforcement regime and deal with the sensitivities of 'law-abiding' citizens who kept violating traffic laws." That discretion—to let "respectable" people off with warnings and saddle others with expensive tickets—"led directly to the problem of discriminatory policing against minorities."

(As a cub reporter in the 1980s, I witnessed this effect in action on a ride-along with a young officer in the local police department. "A big American car full of Black kids pulls out in front of us," I later wrote. "'That would be a fun one to stop,' says Officer A. 'If I had time, I'd follow it around until I found some excuse to stop it. That's how you find stuff: drugs and guns.'")

The Stanford Open Policing Project analyzed 100 million traffic stops from 2011 to 2018 and found clear evidence of racial discrimination. The study's simple but effective methodology was to compare traffic stops during the day, when the driver's race was clearly visible, with those at night. The results were striking. Under cover of darkness, racial disparities in traffic stops dropped significantly. Researcher Emma Pierson's conclusion: "The police treat Black and Hispanic drivers differently from identically behaving white drivers." For instance, police officers search the vehicles of Black and brown drivers based on less evidence than they require to search those of white drivers.

Other studies of stops—both in traffic and otherwise—undertaken by individual police departments have come to similar conclusions in New York City, Los Angeles, and Ferguson, Missouri. In the latter study, which followed the 2014 police killing of Michael Brown, then–attorney general Eric Holder said that the DOJ's investigation "showed that Ferguson police officers routinely violate the Fourth Amendment in stopping people without reasonable suspicion, arresting them without probable cause, and using unreasonable force against them."

A wave of reforms followed those investigations. New York greatly curtailed its "stop and frisk" policy after 2015, following a federal judge's ruling that it was unconstitutional and discriminatory. Los Angeles limited random car stops in 2019. After Ferguson, Barack Obama's Justice Department initiated national policing reforms, but those were quickly abandoned by the Trump administration. Now, after the death of George Floyd and the nationwide Black Lives Matter protests, Attorney General William Barr has flatly denied that America's police departments suffer from systemic racism, blaming the notorious killings on a few bad apples. (President Trump went further, calling Black Lives Matter "a symbol of hate.")

The Movement for Black Lives has called for "defunding the police," shifting the money to alternative response strategies, health care, and community investment. (Some cities have made modest moves in that direction, like Milwaukee's proposed 10 percent cut to its police budget.) Proposals by M4BL and others focus on restricting the scope of police power—demilitarizing forces, repealing the "qualified immunity" that protects officers from lawsuits over their actions, and establishing non-police emergency-response services for people suffering from mental health crises. Polls show that the majority of Americans support sweeping police reforms.

One way to remedy the system that killed Philando Castile, Sandra Bland, and Samuel DuBose is to improve police training, hire more people of color, and hold officers accountable for their actions. But there's another, perhaps simpler way.

"I'm looking at all this," says Darrell Owens, co-executive of East Bay for Everyone, a Bay Area housing, transportation, and racial justice organization, "and I'm like, if you're going to issue a citation for a lane merge or a broken taillight or expired tags, why does it require a gun?" In response to the problem of systemic police racism as expressed through traffic stops, his organization and some others are proposing a radical systemic answer: Remove the police from their traditional role of regulating vehicles.

On July 15, the Berkeley City Council moved to do just that. It voted to establish a new, unarmed Department of Transportation to respond to traffic infractions "with a racial justice lens." In Los Angeles, four city councilmembers have proposed a similar system. "For years, police officers have used traffic enforcement as an excuse to harass and demean Black motorists while violating their rights," said councilmember Marqueece Harris-Dawson. "We do not need armed officials responding to and enforcing traffic violations."

The idea of de-policing transportation is an inspiration that could perhaps only have come out of the current confluence of events: a disastrously managed pandemic, growing climate chaos, the largest social movement in US history demanding wholesale changes in policing and respect for Black lives, and the blazing dumpster fire of the Trump administration.

The scene was set at the start of the coronavirus pandemic, when the nation's initial lockdown forced people to take a hard break from their transportation habits. With fewer people commuting and others sheltering at home, automobile traffic largely disappeared. Slowly, bicyclists reclaimed empty streets that were suddenly safe for even the youngest riders. When cafes and restaurants opened up for curbside delivery and outdoor dining, they added distanced tables in what used to be parking places. Some cities closed traffic lanes to accommodate the new alfresco food service.

For many, it was the first realization that there might be something to be said for the New Normal. Oakland, California, instituted what it called Slow Streets. "The COVID-19 pandemic is changing many aspects of how we live, move about our cities, and get essential physical activity," says the project's website. "The City of Oakland is launching Oakland Slow Streets to support this new way of life." The city closed more than 20 miles of streets to through traffic in favor of cyclists and pedestrians and to provide safe access to food-distribution sites. Seattle instated a similar program, and even Houston—Houston!—passed a Walkable Places ordinance, allowing a greater density of buildings near public transit, expanding sidewalks, and increasing parking for bicycles.

"I saw lots of Black and brown youths riding their bikes on [Oakland's] Slow Streets," Owens says. "There was this idea that the Slow Streets would be without police enforcement. That makes it safer for everyone."

Otherwise, it turns out, bicycling while Black is as dangerous as driving while Black. A Bicycling magazine study of three metro areas found that Black riders in Oakland were stopped more than three times as often as white riders. In Los Angeles in late August, sheriff's deputies attempted to stop Dijon Kizzee for "riding a bicycle in an unlawful manner." Kizzee fled and was shot dead.

Changing the way traffic is enforced, Owens says, is only half the solution: "It's about two principles: de-escalation and prevention. De-escalation is removing police from traffic enforcement. If we're doing traffic enforcement, it has to be equitable—it can't lead to these severe imbalances and racial outcomes targeting Black and brown communities. At the same time, we have to design our streets so that people aren't committing violations in the first place, like a bicyclist who gets a ticket because he's riding on the sidewalk, which I personally got pulled over for. I rode on the sidewalk because there's no safe bike lane! The solution is more bike lanes, more public transit, less driving. That's the solution that ultimately curves traffic violations down to zero."

In a June report, the New York City grassroots organization Transportation Alternatives made a similar case for whatit called "self-enforcing streets." It called on the city to reallocate significant portions of the NYPD's budget to bicycle- and pedestrian-friendly street design and to automate large portions of traffic enforcement with the speed and red-light cameras that have been shown to reduce the number of people killed in crashes by nearly half. With its unblinking, color-blind gaze, the red-light camera is immune to the special pleading of the white and wealthy to be let off with a warning. It judges Black and white equally: Did you run the red light, or did you not? Those who did, instead of being confronted by an armed police officer, would simply receive a ticket in the mail.

This article appeared in the November/December 2020 edition with the headline "Systemic Car-Ism."

Traffic Without Traffic Cops

The California Bicycle Coalition is one of many organizations advocating for reducing police departments' role in traffic management and redirecting funding and focus to transportation departments, social workers, and others. What follow are its recommendations for how California—and, by extension, other states—could make this happen.

- Apply funds from police budgets to bicycle-safe street design, making streets "self-enforcing"—for example, by limiting the ability of cars to speed.

- Automate traffic enforcement with speed and red-light cameras as well as cameras on buses.

- Legalize the "Idaho stop," so named after a 1982 Idaho law that allows bicycles to treat stop signs as yield signs and red lights as stop signs.

- Decriminalize jaywalking, a concept invented by carmakers to blame pedestrian fatalities on the victims.

- Make public transportation—including bike and scooter sharing—free.

- Assess traffic fines based on income, as is done in Finland.

The Magazine of The Sierra Club

The Magazine of The Sierra Club