An Astronomer's Life in Transit

Sara Seager navigates her course after a difficult loss

"Stars represent more than possibility to me," writes Sara Seager in The Smallest Lights in the Universe: A Memoir (Crown, 2020). "They are probability. . . . Each star was, and still is, another chance for me to find myself somewhere else. Somewhere new."

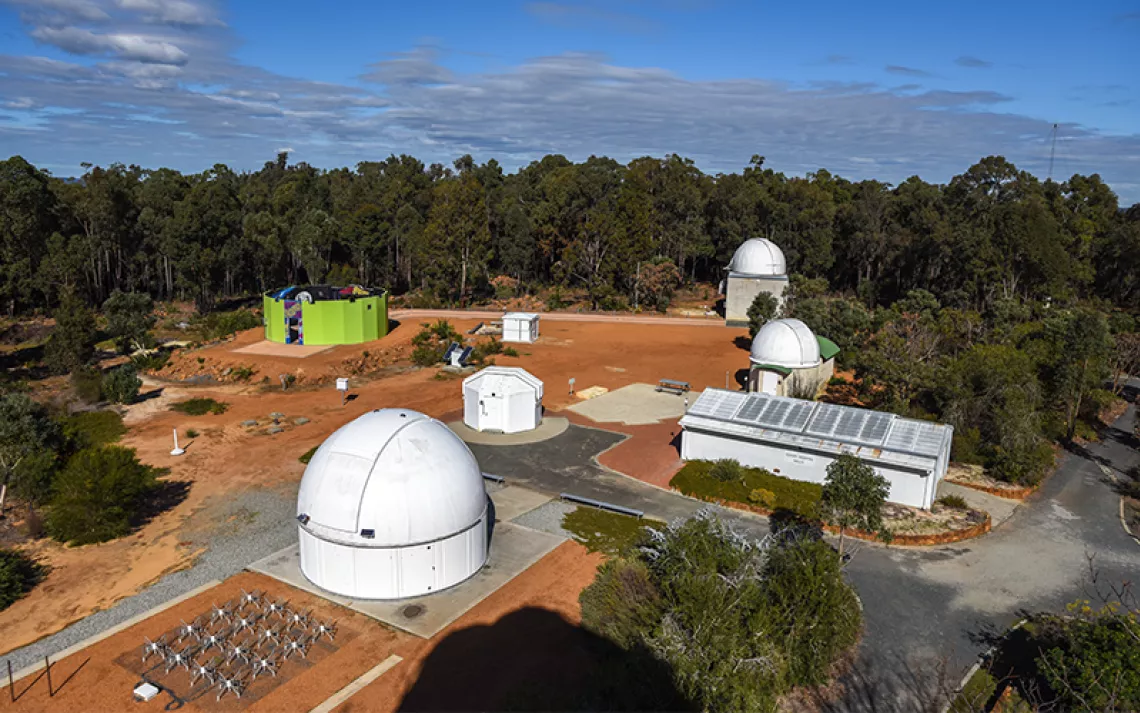

An MIT astrophysicist and planetary scientist, Seager has devoted her career to studying exoplanets—other worlds orbiting distant stars. The book chronicles her groundbreaking research (for which she won the prestigious Sackler Prize in 2012) and the convolutions of her personal life. After her husband dies of cancer, she struggles to maintain a demanding job while caring for two small children. Her dedication to her work is the gravity that pulls her, and the reader, through the turmoil.

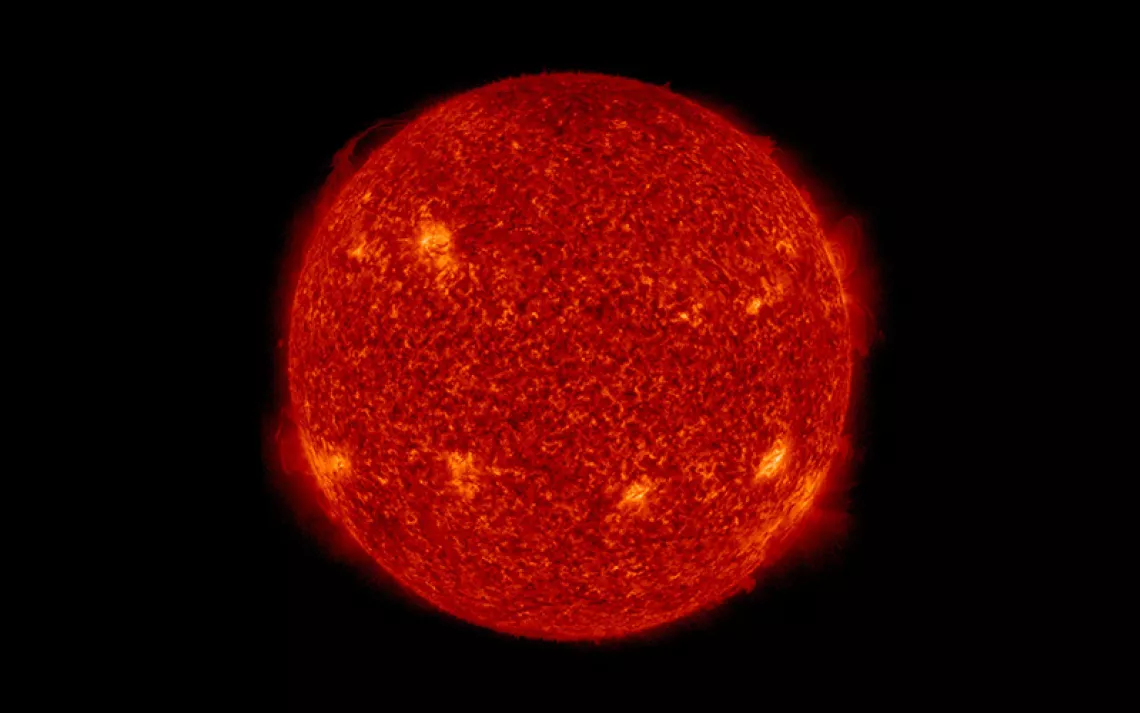

The Smallest Lights in the Universe is an unusual memoir, one as tender as it is technical. Seager traverses rocky emotional terrain—her search for love and meaning in the aftermath of devastating loss—in between elucidating complicated astronomical concepts. A teacher at heart, she deftly explains how planets hundreds and thousands of light-years away cannot be observed directly, only when they pass in front of their parent star and its light dims. This astronomical event, known as a transit, serves as a guiding metaphor for the book. Seager's own story is full of comings and goings, sudden brightenings and dimmings. The movements of people, of course, are far less predictable than those of celestial bodies. Our eyes, she suggests, must adapt. "Sometimes you need darkness to see," Seager writes. "Sometimes you need light."

This article appeared in the July/August 2020 edition with the headline "Life in Transit."

The Magazine of The Sierra Club

The Magazine of The Sierra Club