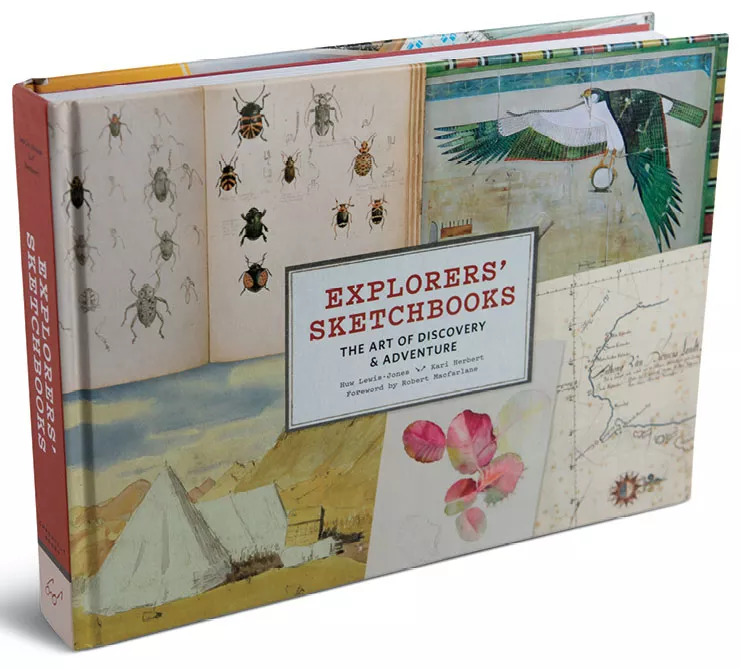

Inside Early Explorers' Journals

Before photography and bullet journals, travelers' sketchbooks marked discoveries

In the heyday of European exploration, cameras weighed 110 pounds and tintypes required a packhorse or oxcart, but sketchbooks and journals were readily available. Explorers' Sketchbooks: The Art of Discovery & Adventure (Thames and Hudson Ltd.) showcases drawings and facsimile journal pages from Carl Linnaeus, John James Audubon, Thor Heyerdahl, and many less-familiar names. Nutshell biographies accompany each entry, and the book's pictorial smorgasbord and alphabetical organization invite nibbling and wonder. Adela Breton's nuanced copies of Mayan frescoes, for example, painted before the days of color photography, are the only polychrome record of these works, whose vibrancy quickly dimmed once they were exposed to the elements. Famed Egyptologist Howard Carter's watercolor of a Horus falcon on the wall of Queen Hatshepsut's mortuary temple resurrects the winged god in all its emerald glory. William Beebe's nightmarish deep-sea fish hauled up in nets and painted by Else Bostelmann could have been creatures from Mars—when they were displayed, the public at first mistook them for figments of the imagination. And mountaineering cartographer John Auldjo's bird's-eye view of Vesuvius, a color-coded map showing successive lava flows, anticipates composite or time-lapse photography.

Sign up to receive Sierra News & Views

Get articles like this one sent directly to your inbox weekly.

With this action you affirm you want to receive Sierra Club communications and may vote on policy designated by the Sierra Club Board.

In an age of slow travel, diaries enabled adventurers to think on paper. Charles Darwin first conceived of the relatedness of species as a "tree of life," doodled in his 1837 notebook months after his grand tour aboard the Beagle. "All art is, I suppose, a kind of exploring," said Robert J. Flaherty, director of the classic film Nanook of the North. This handsomely designed and produced volume elevates journeying to art.

This article appeared in the May/June 2019 edition with the headline "Journaling 19th-Century-Style."

The Magazine of The Sierra Club

The Magazine of The Sierra Club